Toad Road yet no Abode

Given the myriad challenges facing wildlife in our province, one of the best things we can do to protect biodiversity in B.C. is to leave key habitat areas intact. As the global climate warms and precipitation patterns shift, having a complete ecosystem within which animals and plants can try to adapt will be essential, and frankly the least we can do given the dire situation many species are in.

Given the myriad challenges facing wildlife in our province, one of the best things we can do to protect biodiversity in B.C. is to leave key habitat areas intact. As the global climate warms and precipitation patterns shift, having a complete ecosystem within which animals and plants can try to adapt will be essential, and frankly the least we can do given the dire situation many species are in.

This is not news to the government, of course. For species ranging from mountain caribou to spotted owls and goshawks, the Ministry of Environment is quick to reference habitat loss as a contributing, if not the main, factor in population declines:

“human activities associated with resource extraction are the ultimate threats to caribou in British Columbia. Human development fragments and alters caribou habitat…“

“[The spotted owl] is at risk in this province because much of its habitat has been adversely affected by logging or lost due to land development.“

“The laingi subspecies of Northern Goshawk requires large areas of old-growth and mature forest. Large-scale timber harvesting removes much suitable nesting and foraging habitat… Because of this, the laingi subspecies is believed to be in jeopardy, and is on the British Columbia Red List.“

Likewise, the government cites habitat destruction as one of the greatest impacts on western toad populations in B.C.

“Development in and around wetlands can destroy or isolate populations.“

To a lesser extent, though still of importance, migrating toads are often killed by traffic as they try to cross roads.

Western toads are considered a species of conservation concern by the government of British Columbia and have been designated a status of special concern by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). In theory, they are protected under the B.C.’s Wildlife Act.

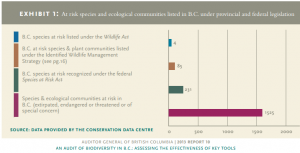

While BC has the most biodiversity in Canada, it is also one of two provinces (the other being Alberta) that has no provincial endangered species legislation. Sadly, BC is the home of more than 1,500 species currently at risk of extirpation or extinction.

Summit Lake, just outside the village of Nakusp in the Kootenay region, is a key breeding area for western toads. Every year, usually around the end of August, young toadlets migrate from the shoreline of Summit Lake, across Highway 6, to upland habitat where they will live for four or five years before they return to the lake to breed. The mass migration sees upwards of a million little toads attempting the crossing, with tens of thousands getting run-over in the process.

Summit Lake, just outside the village of Nakusp in the Kootenay region, is a key breeding area for western toads. Every year, usually around the end of August, young toadlets migrate from the shoreline of Summit Lake, across Highway 6, to upland habitat where they will live for four or five years before they return to the lake to breed. The mass migration sees upwards of a million little toads attempting the crossing, with tens of thousands getting run-over in the process.

Hoping to help, nearby communities hold an annual Toadfest where people carrying the migrating western toads from the curb to the forest in buckets. The provincial government has also tried to address the problem by building directional fences leading to toad tunnels that allow the toads to safely cross under the highway. This amounts to an innovative solution and $200,000 investment in the protection of an increasingly threatened species. In the Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure’s employee newsletter about their work they described the mass movement of western toads from Summit Lake to the forest as “among the great wildlife migrations in the world.”

Unfortunately, the story doesn’t end there. After being safely escorted across the highway, via toad tunnel or bucket, the toads will now find themselves in a forest slotted for logging. Road building began last week and there are plans in the works to clear cut the 30 hectares where the toads hibernate.

Unfortunately, the story doesn’t end there. After being safely escorted across the highway, via toad tunnel or bucket, the toads will now find themselves in a forest slotted for logging. Road building began last week and there are plans in the works to clear cut the 30 hectares where the toads hibernate.

To their credit, the Nakusp and Area Community Forest (NACFOR) logging company has drafted a toad management plan and identified small habitat features that they’ll try to leave intact. I commend NACFOR for exploring ways in which they can continue to harvest the timber while also being mindful of this species of special concern, but it is really the government that should be in the leadership role here.

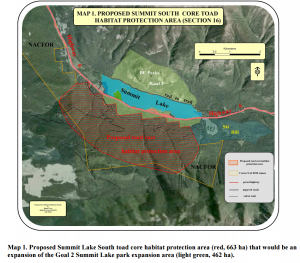

Protection of core terrestrial habitat – defined as “the spatial delineation of 95% of the population that encompasses terrestrial foraging, breeding, and overwintering habitats rather than buffers” – is seriously recommended in the scientific literature for amphibians (Semlitsch and Bodie 2003, Browne and Paszkowski 2010, Crawford and Semlitsch 2007). If the existing provincial park at Summit Lake were expanded to include the forest within roughly two kilometers of the lake the protection of core terrestrial habitat would likely be achieved, wildlife biologist Wayne McCrory said in his analysis of the situation.

Protection of core terrestrial habitat – defined as “the spatial delineation of 95% of the population that encompasses terrestrial foraging, breeding, and overwintering habitats rather than buffers” – is seriously recommended in the scientific literature for amphibians (Semlitsch and Bodie 2003, Browne and Paszkowski 2010, Crawford and Semlitsch 2007). If the existing provincial park at Summit Lake were expanded to include the forest within roughly two kilometers of the lake the protection of core terrestrial habitat would likely be achieved, wildlife biologist Wayne McCrory said in his analysis of the situation.

The province has been criticized for failing to set aside adequate habitat to protect caribou, spotted owls and goshawks and this toad situation illustrates just how reluctant the B.C. government is to remove forest from the logging land base. The key western toad forest habitat around Summit Lake is a relatively small, very specific area that could be included into the existing provincial park. This would represent a minor exemption from their 9,816 hectare total operating base.

The creation of the toad tunnel represented an admirable step forward for the government’s approach to wildlife issues. Granting approval to log their core terrestrial habitat represents more of a smoking bulldozer ride back – squashing all their advancements in the process.

The creation of the toad tunnel represented an admirable step forward for the government’s approach to wildlife issues. Granting approval to log their core terrestrial habitat represents more of a smoking bulldozer ride back – squashing all their advancements in the process.

“Be an advocate for amphibians – protect toads and their habitat in your neighbourhood,” reads the government’s BC Frog Watch website.

Good advice, that I respectfully urge the BC government to follow by protecting western toad habitat around Summit Lake before it’s too late.

2 Comments

As usual , you are covering all the problems that we should know about .

Most of us have some area of involvement or interest in ecological subjects, but the ability to survive is also strongly tied to the healthy habitat for all living things and our appreciation of the necessity of balance, both in all living things and the inanimate.

As always , My thanks and appreciation

Thank you Enid.