Introducing new greenhouse gas reduction targets for British Columbia

Today in the legislature we debated Bill 34, Greenhouse Gas Reduction Targets Amendment Act, 2018 at second reading. This bill repeals the previously legislated greenhouse gas reduction target of 33% relative to 2007 levels by 2020 and adds two new targets: a 40% reduction of greenhouse gases by 2030 and a 60% reduction by 2040 relative to 2007 levels. The 80% reduction target for 2050 relative to 2007 levels remains the same.

The bill also enables the Minister of Environment to set sectoral targets. It further requires biannual reporting on the risks facing British Columbia as a consequence of climate change as well as the government’s response to these risks. This reporting requirement is a direct response to a recommendation of the report: Perspectives on Climate Change Action in Canada—A Collaborative Report from Auditors General—March 2018.

I spoke for the better part of an hour in support of this bill. I began by outlining the history of climate change policy in British Columbia and how, starting in 2012, our province moved from being a leader to a laggard. I further focused on the incredible opportunity for innovation that these new targets provide. And I laid out why it is not possible to reduce emissions to meet these bold new targets while at the same time substantially expanding the fossil fuel sector and in particular LNG in our province.

Below I reproduce the text and video of my speech at second reading

Text of Speech

A. Weaver: I rise to speak in favour and support of Bill 34, Greenhouse Gas Reduction Targets Amendment Act, 2018. This act is putting forward a number of amendments to the original Greenhouse Gas Reduction Targets Act, which was assented on November 29, 2007. That act has three parts to it: one with respect to future greenhouse gas emission targets, one with respect to carbon-neutral public sector and one that had some general provisions.

It is on the first part that the amendments are being put forward today. Under three main areas, the first, of course, is that new targets are being added for 2030 and for 2040. The government is proposing a 40 percent reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, relative to 2000 levels, and a 60 percent reduction, relative to 2000 levels, by 2040.

In addition, we know that there are sections being added here to give the minister executive power through the Lieutenant-Governor-in-council to provide sectoral reduction targets as we move forward.

In addition, and in direct response to the federal Auditor General’s report, the government is proposing to have — starting in 2020 and reporting every two years after that — a report that will be introduced that will discuss the termination of the risks that could be expected from changing climate, the progress that has been made toward addressing those risks, the actions that have been taken to achieve that progress and the plans to continue that progress.

I’d like to go back to the original act in 2007 that’s being amended. To me, that was a very important time in my life, because 2007 was the year in which the IPCC — that’s the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change — released its Fourth Assessment Report: Climate Change. In that year, they also received the Nobel Peace Prize.

I remember that year very, very well. I remember that year because of the fact that the B.C. government at the time, under the leader, Gordon Campbell, decided that this was an opportunity that B.C. could not afford to miss out on. Gordon Campbell, the Premier at the time, recognized, as did his Environment Minister, Barry Penner, that having a climate change greenhouse gas reduction strategy is essential to, say, having a vision. It’s, essentially, exactly the same as having a vision for a renewable, clean 21st century economy that brings prosperity, not only for the present generation but also for future generations thereafter.

He recognized that the very first piece of legislation that needs to be introduced prior to bringing in steps to actually mitigate greenhouse gases was setting a goal. That goal in 2007 in the act that received royal assent on November 27 was greenhouse gas reduction targets.

I sat in the audience proudly watching that day when the bill was read here, as I see young children from a school here. I sat where they sat that day and listened to the minister at the time, Barry Penner, bring in this legislation. I felt proud to be a British Columbian. I told my colleagues around the world to look at the jurisdiction we had. I’ll come to that in a second.

It was not just about the goal, the target that was put in. It was the subsequent legislation that was brought through in a diversity of arrays.

But in 2007, something happened. Mr. Campbell, the Premier, recognized that what we need to do is we need to send a signal to the market in British Columbia that we are going to be leaders in the new economy. We see the emergence of a clean tech sector. We see the emergence of the renewable energy sector, and we see the emergence on investments by companies in reducing greenhouse gases. A lot of that was done by the subsequent measures that were brought in place.

Also, I talked about the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Targets Act. That was a goal that subsequently was buttressed by a number of measures brought in through, for example, the Carbon Tax Act, which was assented to on May 29, 2008; the Greenhouse Gas Reduction (Cap and Trade) Act, which was assented to on May 29, 2008; the Greenhouse Gas Reduction (Emissions Standards) Statutes Amendment Act, which was assented to on May 29, 2008; the Greenhouse Gas Reduction (Renewable and Low Carbon Fuel Requirements) Act that was assented to on May 1, 2008; the Utilities Commission Amendment Act that was assented to on May 1, 2008; the Local Government (Green Communities) Statutes Amendment Act, which received royal assent on May 29.

We have the Greenhouse Gas Reduction (Emissions Standards) Statutes Amendment Act, which I already mentioned. The Greenhouse Gas Reduction (Vehicle Emissions Standards) Act — another act assented to on May 29. And then we have the Utilities Commission Amendment Act. Finally, we had the Clean Energy Act, brought in on June 3, 2010.

During that time, as British Columbia was leading up to the Winter Olympics, a very strong signal was being sent to the market. I remember, as part of the Climate Action Team, the very first climate action team, the multitude of meetings that we had as we made recommendations to government about the types of policy measures they might consider. We were tasked primarily with coming up with interim targets for 2012 and 2016.

We came up with targets that…. In 2012, we were putting forward that we believed that government should seek to reduce emissions by 6 percent, relative to 2007, by 2012. And by 2016, the second target that we were tasked with providing recommendations for…. We came up with 18 percent by 2016.

Government was on track. In fact, it made its 2012 target, based on the policy measures that were put in place. We knew, and government knew at that time, through wedge analysis, that we were not going to make the 2020 target of 33 percent reductions by 2020 with the policy measures and those bills and the statutes on the table, and more needed to be done.

Despite what the member for Kamloops–North Thompson suggests, there was no plan for 2040. The fake numbers brought up about somehow this was part of the government’s plan…. I recognize that he wasn’t there, and he’d probably throw his hands up to say: “What do I know? I wasn’t there.”

However, the reality is that I was there. I was there, working on the Climate Action Team. I was meeting with the Premier at the time — Gordon Campbell — and the Minister of Environment numerous times during that time in an advisory capacity.

As I say again, I was proud to be a British Columbian, because Mr. Campbell recognized the economic opportunity associated with dealing with greenhouse gases, associated with being clean instead of polluting.

All of this came to an end with a switch in leadership. The first crack in the wall or hole in the dike started in June, July of 2012 when LNG was excluded in the Clean Energy Act. So that energy would have to be renewable unless it was being used in the compression of liquefied natural gas. That was the first act.

But it became far more aggressive towards dismantling the policies, and that culminated in 2014, in the Greenhouse Gas Industrial Reporting and Control Act, wherein we in this Legislature repealed the Greenhouse Gas Reduction (Cap and Trade) Act that was assented to on May 29, 2008. We repealed that act, an act that business had actually sought.

Even today, in speaking with heavy point source emitters, they wish that we had that legislation in place. Why, of course, is that we try to meet our targets. We have to recognize that in our society there’s a diversity of emitters. There are large point source emitters, like cement manufacturers, like Rio Tinto Alcan, like pulp mills or paper mills. These large point source emitters are subject to the carbon tax, but the original intention back in the day, back in 2007 and 2008, was that a regulatory framework was put in place. That enabling framework was there, through the cap-and-trade legislation that would allow for the inclusion of large point source heavy emitters, while exempting them from the carbon tax.

So they’re still covered by emissions pricing, but it’s internal emission pricing within heavy industry that allows the most efficient investment of money to reduce emissions.

This is the approach California has done with large heavy emitters. This is the approach Quebec has done. This is not the approach of some other provinces or certain states, but many jurisdictions around the world have cap-and-trade legislation or enabling legislation — some more aggressively so than others.

So with the repeal of that legislation, large point source emitters were left wondering what to do. They were left troubled by the fact that they’re now going to be incorporated into an emissions pricing, a straight-up pricing, and that really what we care about is internally reducing our emissions in British Columbia by spending money on the most efficient and effective ways of doing that.

The Rio Tintos of this world that have spent billions of dollars on upgrading their facility to reduce emissions by 50 percent at the same time would potentially be in trouble if it’s suddenly only a carbon tax approach, as opposed to a cap-and-trade approach, which would have given them recognition for early adoption of measures that were subsequently brought in. That would be allowed and possible within the cap-and-trade system.

So I still hope government, one day, will be bringing in that legislation. You don’t have to go far to find out where it is, because it’s right there in the legislation that we repealed in 2014 in the Greenhouse Gas Industrial Reporting and Control Act. As a little sidebar, you’ll recall that I proposed an amendment, which didn’t pass, to rename it the Greenhouse Gas Increase Industrial Reporting and Control Act back in the day.

Coming back to the issue of emissions. We now know, in British Columbia, that we have two new targets set in this bill — 40 percent by 2030 relative to 2007 and 60 percent at 2040 relative to 2007 — and an old target of 80 percent by 2050.

Now why that 80 percent number is critical is that, while some might cynically say, “Okay, it means we don’t have to do anything, and other governments are responsible,” that number sends a signal to market, a very strong signal to market that government should listen to. And that signal is this: we can no longer spend any more money investing in fossil fuel intensive infrastructure in the province of British Columbia today, because we know that we’re not going to tear it down tomorrow.

Instead, we should be transitioning away from fossil fuels to renewables and the low-carbon economy. We don’t build a coal-fired electricity plant to tear it down tomorrow. We don’t build an LNG facility — a two-train, a four-train LNG facility — in Kitimat to tear it down tomorrow. We build them to last 40, 50 years. We build them to last until 2050. Therein lies the conundrum that government has if it’s trying to talk on the one hand about LNG and on the other about meeting climate targets.

The previous government lost all credibility on that file, as they were talking 23 permits and five big plants. I mean, it was just outrageous, the rhetoric that was coming from the opposition, then-government, about wealth and prosperity for one and all from LNG that clearly didn’t transpire.

I recognize that the present government has taken the giveaway one step further with reduced electricity rates, exemption of increase in carbon tax. It has also talked about repealing the LNG income tax, which I hope my colleagues opposite will not support the repeal of, as we will not support here on the B.C. Greens. But coming back to that….

In 2007 —that is the reference point upon which all future reductions are measured against — we in British Columbia emitted 64.7 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent.

Now, the carbon dioxide equivalent means that we know that methane, on a 100-year timescale, is much more powerful, as is nitrous oxide or certain CFCs or HCFCs. They’re more powerful on a molecule-per-molecule basis in terms of their absorptive ability on greenhouse gases. So we convert them, all those other greenhouse gas emissions, to the carbon dioxide equivalent.

We had 64.7 megatonnes. In 2008, we had 64.7 megatonnes of emissions again. In 2009, not because of any grandiose immediate policy — although, we recognize that there was a very strong signal at the time sent to the market that the carbon price was going up, and there was investment at the time — emissions dropped to 61.1 megatonnes. Part of that, too, was because of the economic downturn that didn’t really hurt B.C. but hurt global economies.

In 2010, we were down to 60.6 megatonnes and in 2011, 61.1 megatonnes. In 2012 — here’s where the policy shift started to happen — 61.9 megatonnes. In 2013, 62.9 megatonnes; 2014, 62.3 megatonnes; and 2015, 63.3 megatonnes. Every single year since the change of leadership of the previous government, emissions went up.

Why did they go up? It was because government sent exactly the wrong signal to market that you want to send if you want to head towards decreasing emissions. Government introduced exemptions on the deep-well royalty credit, not only for deep wells but now for shallow well. Heck, for any well, royalty credits now exist.

Did you know that ten years ago we used to get $35 or so for every 1,000 cubic metres of natural gas produced in the province of British Columbia, as a royalty — $35. Now it’s less than $3 as a royalty. It was more than ten times that just a decade ago. It’s going down still. At the same time, the production of natural gas has gone up and up. Why wouldn’t you take it out, if we’re giving it away?

Literally, we give this resource away — this beautiful resource, for applications that we yet have no idea of, in the future. We know that these molecules are very useful in the petrochemical industry. We know they’re very useful in other industries for creating fertilizer and creating methanol. We know that we can use our natural gas resources in a diversity of ways. Burning it is one of the most ridiculous ways, and frankly, generations after us are going to look to our generation and say: “Why did you squander that resource? Why did you burn it when the most powerful source of energy, the sun, is free — as is geothermal energy?”

Let’s come back to the targets, because it’s critical that we do that. I’ve pointed out that in 2015, now we’re at 63.3 megatonnes. That’s the last reporting year. For the next little bit, I’ll assume that we haven’t changed from that — not because that’s correct or wrong, but because that is the last year we have reporting data officially done for Canada in the United Nations framework convention on climate change.

There were 63.3 megatonnes of CO2 equivalent from B.C.in 2015. Let’s suppose we know that we’re going to add four trains of LNG facilities. Shell Canada talks about a two-train facility right now, but you don’t build two trains not to build four trains. So let’s suppose we talk about a four-train facility and that that’s really the direction we’re heading.

Well, we know, as I’ve mentioned already, that if we start at 64.7 megatonnes — that’s the 2007 reference value that this legislation is referring to — we know that our 2030 target of a 40 percent reduction of that 64.7 megatonnes means we have to go down to 38.8 megatonnes by 2030, to 25.88 megatonnes by 2040, and to 12.9 megatonnes by 2050. So that 64.7 megatonnes in 2007, under the legislation before us, must drop to 38.8 in 2030, 25.9 in 2040, and 12.9 in 2050.

Now, if we’re going to add a four-train LNG facility, we’re going to add 8.6 megatonnes — that’s before some of the recent estimates that I could talk about shortly, about fugitive emissions — and adding on to that. So our new reference case is actually…. Well, we’re basically adding 8.6 megatonnes to that 2015 value. The 2015 value was 63.3 megatonnes, we’re going to add 8.6, and we’re going to come up to 72.9 megatonnes. That 72.9 is our starting point — because we’re adding 8.6 — for reductions.

Let’s suppose that we know we’re going to put in a four-train LNG facility. We know that Shell won’t build that today to tear it down tomorrow. It’s going to last for several decades. They’re not going to invest billions of dollars just on a whim. It’ll last decades. So what does this mean for greenhouse gas reductions in every other sector?

Here are the numbers. We know that if we have a four-train LNG facility — that’s going to be constant; it’s going to be there; we’re not going to tear it down — then every other sector in our economy, other than that facility, must drop its emissions by 52 percent by 2030, down to 30.2 megatonnes, by 73 percent by 2040 and by a whopping 95 percent by 2050.

Now, reflect upon this. One four-train LNG facility in Kitimat will produce 8.6 megatonnes of emissions, which aren’t going to be around just for tomorrow and then we tear it down. That’ll be around for decades. If we add those four trains and we believe these targets that we’ve actually put forward, then we need every other sector of our economy to reduce its emissions by 95 percent. That means telling Rio Tinto Alcan: “I’m sorry, but you have to shut down.” That means saying nobody can drive fossil-fuel-combusted vehicles anymore, nowhere in B.C. That means telling heavy industry left, right and centre they have to shut down because we’re already at that with things with landfills, which we have to close down as well.

There’s a staggering disconnect, and to be fair to the politicians in this room, it’s not just here; it’s globally. There’s a staggering disconnect between science and policy here in B.C., in Canada and internationally. I’ll come back to that again in a couple of seconds.

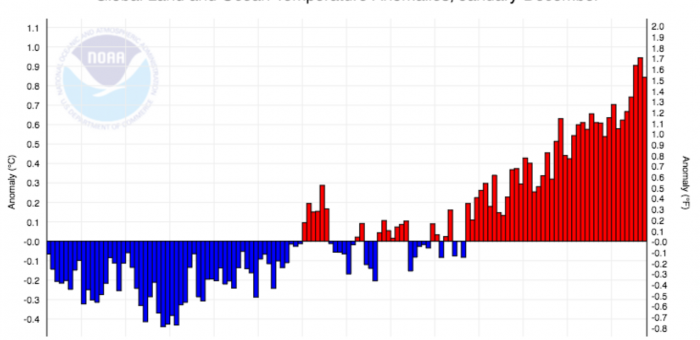

Leaders around the world signed, in 2017, something called the Paris accord, which committed…. Canada was one of the signatories of it. Despite the fact that Trump wants to get out of it, he can’t for years to come. It committed to keep global warming to below 2 degrees relative to preindustrial levels. They would actually keep it substantially below 2 degrees. So what can science say? It can say this. We know the world has warmed 1.1 degrees already. We know that 2016 was the hottest year on record, followed by 2015, 2017, 2014, 2010, 2013, 2005 and 2009.

For those people who’ve been following this climate change debate, like I have, for so many years, you should be asking the question: where were all those skeptics who said we’re in a cooling period? What happened to them? Are they finding some other argument now?

Believe it or not, scientific communities understood thermometers quite well for several centuries, and in fact, the world is warming, and we can measure it. Forty percent of Republicans in the U.S. don’t believe there’s solid evidence that the world is warming. Frankly, they don’t believe in the existence of thermometers. That’s the scale of that.

Coming back, we know the world has warmed by 1.1 degrees. We know that if we do no more, if we do nothing but keep existing greenhouse gas levels fixed at the present-day values, we’re going to warm by another 0.6 degrees. That takes us to 1.7 degrees, and we know that the permafrost carbon feedback is going to give us another 0.2 to 0.3. We know that if we do no more than just keep the levels like they are now, we’re going to warm towards 1.8 or 1.9. Yet emissions continue to go up year after year in places like Canada and elsewhere.

The disconnect that I mentioned about here in British Columbia extends globally. It’s particularly in Canada. I’ll come back to this in a second, but in Canada, Mr. Trudeau signs with a smile that we’re now part of the global agreement. On the one hand, he says we’re going to actually bring in place a climate plan in Canada to meet our Paris targets. It’s actually Harper’s plan, but that’s an aside. I’ll come to that in a second. He brings in…. He’s done nothing, argues we need to build pipelines to have a climate plan. It makes no sense because what Paris says, not only to Canada or British Columbia but to the world, is that effective immediately, we must turn the corner and stop investing in new fossil fuel infrastructure that will continue to be around for decades to come.

As I say again, we don’t build a coal-fired plant today to tear it down tomorrow. It’s about making the right choice of investments today that will affect tomorrow. I’ll come back to some of the ramifications and the importance of this bill later.

Coming back to federally in this context of meeting our legislation. Federally, ironically, people like me are beginning to look quite fondly upon the time of Mr. Harper because he did nothing on the climate change file — nothing at all — and Mr. Trudeau has done negative by stumping for pipelines.

It’s remarkable that we have this cognitive dissonance happening politically, federally, at a time when most of the world is actually recognizing the seriousness of this. Norway, for example, a nation that recognized that climate change is not only something to be concerned about; it’s also an opportunity. Did you know that 40 percent of new cars in Norway are electric? They’re electric today. Netherlands, India and other jurisdictions have announced that all new cars will be electric by 2030.

Here in British Columbia, we have an opportunity for leadership, and the first step in claiming that leadership is setting in place targets. Because it is those targets that allow the civil service, allow the modellers, to do their wedge analyses so that we can actually start to understand what the effects of certain policy measures are in terms of future greenhouse gas reductions. That work is ongoing as I speak. I’m very pleased that it is ongoing as we speak.

Coming back to the LNG relationship with this legislation. I’ve heard it say that LNG Canada is talking about a two-train LNG facility instead of a four-train. I’ve got the numbers for a two-train LNG facility as well, and they’re no different.

If LNG Canada invested a two-train LNG facility in Kitimat, all other aspects of our economy would have to drop their emissions from 63.3 megatonnes in 2015 to 34.5 in 2030, 21.4 in 2040 and 8.6 in 2050. That’s a 46 percent, 66 percent and 86 percent reduction — an 86 percent reduction, everything else other than LNG Canada.

These are big numbers. These are very big numbers, and very big numbers cannot be met without bold plans. That is what we’re looking forward to. We’re looking forward to seeing that plan, because frankly, I got into politics back in 2012, not because I saw this wonderful opportunity for a career in politics. That was not the intention.

It’s that I was involved very intimately with Gordon Campbell’s government and the development of the climate policy and climate strategies and his government — which, hon. Speaker, I note you were part of at that time — as they put British Columbia on the map as a leader internationally in both dealing with the challenge and recognizing the opportunity of what greenhouse gas mitigation does.

We were leaders, and then I saw that start to crack apart in 2012. I could not stand by and say to my students, who would come…. You know, I would talk in these classes about framing the whole issue of climate change as an issue of intergenerational equity, because it is. Today’s generation, our decision-makers, won’t have to live the consequences of our decisions, and those who do, better get participating in our democratic institutions, because they’re going to inherit those consequences.

They don’t. I would ask them: why don’t you vote? Why is it that 30 to 40 percent of youth between 18 and 24, until the last election, voted federally? They would say to me that all politicians are corrupt. All they want to do is line their policy…. I’d say to them, no, no that’s not the case. People go there for a right reason. If you don’t like them, run yourself or find someone to run, but this is the system that we have.

In 2012, I’m giving the same lecture, and I’m looking at myself in the face and saying I’m a hypocrite. I can tell them that if they don’t like what’s happening, they should run themselves, so I ran. I ran with the B.C. Green Party. Let me tell you, it is not the easiest path to this Legislature, as my friend from Saanich North and the Islands and my friend from Cowichan Valley will attest. Running with the B.C. Green Party, a party that had elected nobody before in any province, is not what you do if you’re looking for a political career in power. You do that out of principle. The same goes for my colleague Adam and my colleague Sonia.

And we’re here. We’re here with 17 percent of British Columbians saying we support you. We were very clear in our campaign that this defining issue of our time is one that we’re here to push, to ensure that British Columbia capitalizes on the opportunities. We can be laggards of yesteryear or we can be leaders of tomorrow. I think British Columbians want to be leaders.

We could talk about revenue. Revenue to natural gas was more than $1 billion dollars a little over a decade ago. And now…. Well, a couple of years ago we actually lost money. Now we’re making a mere few tens of millions of dollars. We are not…..

Hon. Speaker, I am the designated speaker. I noticed that the light has come on.

We are not going to continue to bring wealth and prosperity to British Columbia if we continue to chase the economy of the past. We are blessed in British Columbia with resources, renewable resources and raw resources like minerals, like gas, like water, like forests. We are blessed with resources that we have a duty and a responsibility to steward for future generations — not only the resources themselves but also the environmental and the social systems that surround them.

That’s why this bill is critical as giving the first step of those targets that will allow the civil service the wedge analyzes to get there. For example, let’s look at the mining sector. British Columbia is blessed with a mining sector. We are some of the world’s leading miners around the world. Many of them started…. Some of them get bought up.

Look at Teck Cominco. Well, it’s now just “Teck.” Teck — an incredible asset to British Columbia. Teck’s a good company, a good steward of the environment. Teck would love to be able to use electric trucks. But there’s no technology out there.

There’s an opportunity for B.C. innovation. There’s an opportunity for B.C. to actually do what Norway is doing in replacing their ferries with electric ferries — with batteries built in Richmond, no less. Why are we not recognizing this innovative opportunity for heavy industry? Electric trucks. We’ve got lots of electricity. We’ve got a company like Teck — a leader, a global leader — ready to adopt. There’s an opportunity.

Here’s another piece of innovation out there. We talk about gas filling stations all over the place. You want to be a leader of the new economy? You recognize that you can get land really cheap on the highway between here and there, halfway between towns, and you could start to put a gas station there. But the gas you’re doing is actually electricity for electric vehicles. When you fill up in a high-voltage 400-volt charger, it’ll take you 30 minutes. You’re going to sit there. You have a cup of coffee. It’s an opportunity for innovation — to start to create charging stations. But that innovation needs government to get out of the way.

Right now in British Columbia, you cannot give away your electricity and ask someone to pay for it unless you’re a registered utility. I have an electric charging station at my house. I’d love to charge the member for West Vancouver–Capilano 35 cents every time he filled his electric car up. But I can’t.

Interjection.

A. Weaver: There we go. My colleague here would charge me 25 cents, and the free market starts to come to play here. Capitalism, free market economy — here we go. He’s charging 25 cents, and maybe my colleague there from Whiskey Creek will say: “I’m going to charge 20 cents, because the Huu-ay-aht have got a generating station there, and they have excess power. We want to charge that power here. Let’s go.”

This is innovation. We in British Columbia used to be leaders in that regard, and now, sadly, we’ve fallen off that. This legislation is the very first step, the necessary first step, mirroring what was done in 2007 by Gordon Campbell to get us back on the right path.

British Columbia has an electric car company here — Electra Meccanica. Our colleague ran in Vancouver–Mount Pleasant, there, against the member from Vancouver–Mount Pleasant. This is a company that builds electric vehicles. It’s traded publicly on the NASDAQ. It builds electric vehicles in Victoria. But now, guess what. The factories are going to be in China and India. He’s got hundreds of millions of dollars of sales coming forward, but in B.C., we should be doing that here.

We should be saying say to Terrace that we get that you have some economic issues right now, because the oil and gas sector is hurting. The price has gone through the floor. But you are on a rail line between Chicago and Prince Rupert. You’re on that rail line, and guess what. We can get your goods manufactured there to market in both the biggest east coast and the Asian markets. But what we need is to attract manufacturing there.

By recognizing that there’s a whole generation of manufacturers who want to be clean and good corporate citizens…. B corp., the legislation I just brought in a couple days ago. Benefit corporations. We could give them that clean energy.

We don’t have to double down on the economy yesterday. We could say that Terrace is the place to go. And 100 Mile House — all of these small communities across our province have their own strategic advantages that make them the place to go for innovation and variety of areas.

Forest fire innovation. There is so much potential there, both in terms of the type of suits that people wear through the suppression techniques for innovation in the forest fire sector. We have innovation in the forestry industry, but we buy our innovation from Finland. There was a government there that recognized that in order to compete, we can’t compete by racing to the bottom. We can only compete if we are smarter. Otherwise, we’re going to give our resources away. We’re smarter, and we’re more efficient. Therein lies an opportunity there.

In those opportunities, those wedge opportunities, we meet our targets at the same time as we bring economic prosperity to British Columbia — not only for this generation but for generations to come. Not doing so is a problem.

We bemoan…. It’s a tragedy that we have the flooding events in the Boundary-Similkameen region this year. We had flooding last year. We had forest fires last year. We had forest fires that took out much of Fort McMurray. This is a story that happens year in and year out, not only in B.C. but everywhere.

As I’ve tried to point out time and time again, the issue of global warming, which this is addressing, is fundamentally a question of intergenerational equity. Do we, the present generation, owe anything to future generations in terms of the quality of environment that we leave behind? If the answer is no, who cares about global warming? Really, it doesn’t matter. Because it just goes to hell in a hand basket, and “I don’t care about future generations.” But if we care, yes, we must act now. Because waiting is too late.

The analogy that’s direct is: you put a pot of water on the stove, and you turn it up to 8. That dial there is essentially greenhouse gas emissions or the level of the atmosphere of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. You turn it up. The water is cool. It starts to warm. I don’t worry about global warming. I don’t care. The thing is on 8. It starts to get a bit warm. You go: “Whoa, this is getting hot.”

It starts to get a little bit warm. I’m going to turn 8 down to 7. It gets warmer. Now it starts boiling. Oh, I better turn it off. You turn it down to zero, but guess what? It’s too late.

The analogy is direct to the world. Seventy one percent of our globe is covered by water. It takes time for the oceans to heat up. Once they do, you can’t cool them right away either. The analogy is direct. And once you get to a stage where you say, “Oh, it’s too warm. We better cool it” — it’s too late, frankly.

Now we worry about the forest fire here and a flood there. And I get that. It’s really important. But it pales in comparison to the plight that’s in store for us. And you can go back and look at what the climate scientists have been saying for decades — it’s been the same thing. Those touting that it’s just somehow some natural cycles — they act like a legal defense team who’ve lost their case. They throw all sorts of public doubt out there, fake news and all, hoping that the public jury will render a not guilty verdict.

But we know that a substantial fraction, something like 60 percent of the world’s species, will be committed to extinction — 60 to 80 percent at the end of this century as a direct consequence of greenhouse gas emissions.

We can’t turn the level of atmospheric dioxide up, on the scale of 100 years, to the levels that haven’t been seen since Jurassic and Triassic and not think there’s not going to be an ecological response. We are literally going back to the Triassic and Jurassic in the scale of a few decades, as we take that captured carbon that was captured in those swamps and the seas and created goal and natural gas that we’re releasing in decades.

Sure, life will go on after an extinction event, and it will come on in a different form. But it certainly will not be life like we know it today. We know that in the big extinction events in earth’s history, when a meteor hit or when we had more intensive volcanic activity, there were 80 percent, 90 percent of marine organisms that went extinct. We know we’re on track to do that now.

We know that the biggest sink of atmospheric carbon is the oceans. We know that the Great Barrier Reef is probably gone, and there’s nothing we can do about it because of the sink of the carbon that exists. We know that many of the ocean’s corals are dead, and they will die forever and there’s not much to do about it. These are just the early stages.

Again, I come to the point of: do we, as a present generation, actually owe anything to future generations because if we do, we must act here now. We must not weigh, for example, one LNG plant against and jobs that may or may not exist five years from now versus the opportunity for success in a new economy that preserves prosperity and the environment that our next generation will actually come to live in.

These are not options. I talk about some of the sad things that I see. One day I see a politician putting sandbags up on a dike, and the next day that same politician is here arguing: “Rah, rah, rah Kinder Morgan and LNG.”

Where’s the disconnect? The disconnect is mind-boggling. Again, we go back to this issue that we’re proposing to deal with here. The greenhouse effect goes back to Jean Baptiste Joseph Fourier in the early 1800s, the first to recognize the atmosphere acts like a greenhouse that allows incoming solar radiation through but blocks outgoing long wave radiation, to act like a blanket to keep the surface warm.

We’ve known about the different effects of a variety of greenhouse gases since the 1860s. We’ve known about the specific role of carbon dioxide in the 1890s. We knew and had the first multisensory projections in the 1930s.

In 1979, when I was graduating from high school, Jule Charney, an MIT climate and atmospheric scientist, was tasked with the first national assessment in the U.S. They came up with the best estimate of the single most important metric, summarizing our cumulative understanding of the world’s response to increasing greenhouse gases.

That is climate sensitivity. Climate sensitivity, by definition, is how much will the world warm if we double atmospheric carbon dioxide levels from Premier-industrial levels, from 280 to 560 parts per million.

In 1979, the very best estimate was between 1½ and 4½ degrees. That was the range. In 1990, the first IPCC assessment — Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change — scores of publications examined. Best estimate:1½ to 4½ degrees.

In 1996, second assessment report, best estimate:1½ to 4½ degrees. The single best estimate of the single most important metrics, summarizing our cumulative understanding of how the world responds to a doubling of carbon dioxide, has not changed from 1979 to 1996, where we’re in the second assessment report.

We move to 2001. We’re now at the third assessment report. The best assessment gives 1½ to 4½ degrees, and then we move to 2007. That’s the Nobel Prize year. It moves to 2 to 4½ degrees. Wow. We’ve changed it slightly. And then in 2013…. I was involved in every report from 1996 through 2013, and that 2013 one was fundamentally frustrating. The report had largely concluded in 2012, and I withdrew from the process when the writ was dropped in the 2013 election, but all the rating had been done.

The 2013 estimate from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, summarizing tens of thousands of papers’ knowledge on this issue, the best estimate of climate sensitivity, the single most important metric summarizing our cumulative understanding of what will happen as a consequence of global warming — that is, how much will the world warm if we double carbon dioxide….? The best estimate was 1½ to 4½ degrees again.

We don’t need more science. What we need is political will, and what we don’t need is more grandstanding on these important issues, which is why I’m excited about this bill. Why am I excited about this bill? Because it provides the first step, as was done in 2007 — the very first step that is necessary to actually head us in a direction. And that necessary step…. This should be taken as a signal.

If government is serious about this bill brought forth, it cannot support the addition of a two- or four-train LNG facility. We just can’t do it. You cannot square that round peg. It doesn’t work. The numbers don’t work, and the last thing this government needs to do is try and play the accounting games that happened towards then end of the last administration’s governance.

We start to get things like: “Okay, I’m going to give you money and take a carbon credit, because you’re not going to not cut down those trees that otherwise you would cut down.” This is the kind of carbon accounting nonsense we get into. If you open that Pandora’s box, you’re going to have to start accounting for forest fire losses as well, and we don’t want to do that, let me tell you.

We started to pay Encana…. They had at the time…. We gave them carbon offset as they actually upgraded some natural gas facilities. Okay. That’s fine, but that was not the intent. The intent was to actually get fundamental changes and send a direction to the economy that we want to move elsewhere. And we have to be careful how we continue with the offsetting.

With that, I will suggest that this debate…. Both my colleague from Saanich North and the Islands and my colleague from Cowichan Valley will be looking to speak to this bill further. I do want to touch upon the last two things that I haven’t marked.

I want to support the minister in his ability to be given the powers to set sectoral targets through regulation. I think that’s important, and he has articulated and identified, in his opening remarks, that he will seek guidance for that from his — I forget the name of this reincarnation; we’ll call it, for the purpose of Hansard — climate leadership team 3.0. He will seek advice from them. They represent a variety of sectors, and I think that’s a good strategy, and I think the approach is a fine one.

I also want to give the minister a lot of credit for adopting the recommendation of the Canadian Auditor General with respect to biannual reporting out of the risks as well as how we are moving towards meeting those risks of climate change.

The risks are very real and very serious and will get worse as time goes one. You know, I could talk about…. For example, we knew since 2000, when a student of mine, Dáithí Stone…. He went to Oxford — I lost touch with him in the last few years — and was a lecturer there after that. He wrote a paper where he analyzed precipitation trends in Canada. We know extreme precip is going up.

We know, for example, we can attribute…. We did this in 2004. Nathan Gillett is a former…. He’s now head of the Environment Canada Canadian centre for climate modeling and analysis. We knew, in 2004, that we could detect and attribute the increasing area of forest fires burnt in Canada directly to human activity. We know that.

We know what the cause is. We know what the precursors are. We need to have ignition. Well, we’ve got lots of lightening. We need to have dry timber, and the way you get dry timber through soil moisture and summer warmth. We know we can detect regional changes in increasing temperature.

Again, I’ve said the same thing since the 1990s. As a climate science community, we know it’s going to happen. We know that we’re going to get an increase in extreme weather events, particularly in precipitation. The 100-year event is no longer a 100-year event; it will become a 25-, a ten-year event, and then it’ll become a 5-year event and so forth. We know we’re going to get that.

We know we’re going to increase our precipitation in our latitudes. We know water here is not going to be an availability issue; it’s going to be a storage issue, because we know we’re going to get increased water in the winter and less in the summer, because we have increased likelihood of summer droughts.

We know that in the winter it’s going to be increasingly likely and more and more extreme events. Ironically, we might get amazing snow years, because if the temperature is slightly below zero, it’s snow instead of rain. So yes, we might get a big snowfall, but that’s exactly what we would expect to get, because it’s winter it’s and cold and we expect increasing amounts — of the warming climate to have more moisture in it.

We expect a northward shift of the storm track, so yes and lo and behold, we’re getting more of these stronger storms hitting our latitude. What would you think? That’s exactly what we’ve been saying: these move further northward. The same in the south. We know artic sea ice is going. We know it’s likely going to be gone in the summer in a few decades. We know that 2017 is right on the edge of setting a new record — the record that was first set in 2007 and then broken, quite dramatically, in 2010. We’re on path to beat it again this year.

We know that global sea ice volume was a record low this year. We know that if we don’t do anything, we’re going to commit 60 to 80 percent of the world’s species to extinction towards the end of this century. We know that we’re going to get increasing droughts. We know that we’re going to flood islands.

We know that there are hundreds of millions of people living on the coasts, and we know that if we get warming to about two degrees, we have a very high probability that we’re committed to seven metres to sea level rise, because that point puts Greenland and the West Antarctic Ice Sheet past the point of no return.

Now, we also know that when there’s a storm — and we know that there are increasingly strong storms — that we actually get storm surges. We know that with the warming water — again, you could do this experiment at home — when you have a high tide, warming water and storms, you get big storm surges, and you start to see things like Hurricane Sandy flooding New York.

Now what happens when New York, which was flooded once, starts to get flooded like that every ten years. Then you add six metres of sea level rise on that. You start to create a problem for our built infrastructure — a problem when you have hundreds of millions of people within ten metres of the coast. The town of Shanghai, the burgeoning metropolis of Shanghai, is less than ten metres from the coast. You get rid of Greenland and west Antarctic ice sheet — it’s pretty hard for them to adapt if you add ten metres of sea level rise. It’s pretty hard for deltas, for Richmond, to adapt if they have ten metres of sea level rise.

It’s not going to happen overnight. This is why the issue is one of intergenerational equity. That won’t even happen in the next 100 years. It takes hundreds of years for that to happen. But, hon. Speaker, let members in this House know that history will not be kind to those of us who stand by and let this happen. We will be judged. So be it if people don’t care, if they don’t care about intergenerational equity. That’s fine. People who don’t have children might not care.

Some people may have belief systems that this conflicts with. They might believe, for example, that whatever is going to happen was meant to happen, and it’s God’s will. As climate scientists, we can’t argue science against faith. You can’t dismiss those views, people within our society, because nobody, no science could ever address the question: do we as a society need to actually deal with this issue? That requires all of us.

What we need to do is we need facts and evidence on the table, and we’ve got to stop listening to rhetoric that’s put forward and doublespeak — like we need to build pipelines in order to have a climate plan. Politicians need to be truthful to the people of British Columbia. They need to know what the consequences of inaction are.

If society believes that you don’t need to deal with this problem, so be it. I happen to think we do, and I happen to think most people do believe we need to deal with this issue. As such, this bill is critical. When we apply this is critical, not only to implement this bill but also the subsequent policy measures that will ensure we will meet targets. Targets have been in place in Canada since the 1980s, when Brian Mulroney introduced the first targets, and we have a litany of missed and failed targets.

Europe met their targets. We have not met our targets here in Canada — not one, not close, not even a little bit close to any of our targets.

I look forward to the subsequent legislation announcement to come, and with that I thank you for your attention, and I look forward to further debate.

Video of Speech

Comments are closed.