New Ways of Funding BC’s Health Care System

“There is a difference between equity and equality and treating everyone exactly the same may not always be fair” – Dr. Livio Di Matteo

Over the past couple months, I have emphasized the need for government leadership and increased government funding if we are to truly tackle poverty and homelessness in our province. Over the course of the next few articles I will begin to outline what government leadership might look like and identify where that funding could come from. In this first post, I focus on health care funding and the Medical Services Plan premium that unfairly burdens low and fixed income British Columbians as well as small business owners with an overly heavy tax burden. In addition, I provide details concerning British Columbia’s under representation in the federal funding allocation for provincial Health Care via the Canada Health Transfer (CHT). As I will demonstrate, British Columbia is receiving $153 million less that it should through this program.

Regressive versus Progressive taxation.

The various forms of taxation available to government generally fall into two broad categories: 1) Progressive taxes; 2) Regressive taxes.

Progressive taxes, such as income or corporate tax, are based on the premise that those who can afford to pay more, should pay more. That is, higher income earners would pay larger taxes than lower earners. This premise forms the foundation of our income tax systems right across the country.

However, in recent years, there has been a general tendency towards reducing various forms of progressive taxation and replacing the lost revenue through increases in a variety of regressive taxes. Regressive taxes, such as the Provincial Sales Tax, are taxes that do not reflect one’s ability to pay. In other words, everyone pays the same, regardless of how much your earn. Perhaps the most obvious example of this is British Columbia’s Medical Services Plan (MSP) premiums.

What is the Medical Services Plan (MSP)?

As noted on the Ministry of Health website “The Medical Services Plan (MSP) insures medically-required services provided by physicians and supplementary health care practitioners, laboratory services and diagnostic procedures.” The MSP requires anyone living in BC for six months or longer to pay monthly premiums for health care coverage. While some individuals can apply for premium assistance, these subsidies dry out as soon as a person earns a net annual income of $30,000 or more. Those who earn more than $30,000 must currently pay a monthly flat fee of $72. This means that an individual who earns $30,000 per year pays the same MSP premium as an individual who earns $3,000,000 per year. And so, it is evident that MSP premiums are perhaps the most regressive form of taxation in BC.

MSP Premiums become even more regressive when you factor in who actually pays them. The fact is, many large employers pay all or part of an employee’s MSP premium as part of a negotiated taxable benefit of employment. But for many, if not most, low and fixed income British Columbians, as well as small business owners, they must pay the costs themselves.

In 2000, the MSP premium for a single individual was $36 per month. Today, that same individual pays twice as much (the same amount that a family of three or more paid 15 years ago). At the same time, personal and corporate income taxes have experienced significant cuts, the consequences of which I will explore further in future posts. The resulting major shifts in taxation have led to the provincial government now bringing in almost as much revenue from MSP premiums as it does from corporate income taxes. In the 2014/15 British Columbia budget, revenue from MSP premiums was expected to be 2.271 billion dollars whereas corporate tax revenue was estimated to be 2.348 billion dollars.

While one can make the argument that reducing MSP premiums allows for lower rates of other taxes, these benefits are often only felt by the wealthiest of the population. In fact, “when all personal taxes are considered (income, sales, property, carbon, and MSP premiums), the higher your income, the lower your total provincial tax rate”. So, while most BC households paid around the same total tax rate back in 2000, with those in the top income bracket paying slightly more, under the current system the wealthiest 20% of households now pay a lower total tax rate than the rest of the population.

Not only do these tax cuts not benefit the majority of British Columbians, but we also must then pay for these cuts in the form of reduced social services. Over an 11-year period, from 2000 to 2011, BC’s tax revenues fell by 1.6% relative to the size of the provincial economy (GDP) resulting in a revenue deficit of about $3.5 billion.

Why do we pay MSP Premiums?

Some may wonder why we have to pay provincial MSP premiums in the first place. After all, we are the only province in Canada to require them. The rest of Canada have moved away from monthly premium charges and instead use general tax revenues, primarily provincial income taxes that are based on taxpayers’ ability to pay, to acquire the funds needed to pay for Medicare services. In fact, after the Alberta government announced its plans to eliminate their premium charges for Medical Services Plan Coverage in 2008, BC was left as the only province to continue to charge these individual flat-rate premiums.

The answer is simple. It’s a choice that successive British Columbia governments have made. It’s a choice to favour regressive over progressive taxation. It’s a choice that puts the interests of the wealthy over the interests of low and fixed income British Columbians as well as small business owners. And the choice is made, in part, to maintain the illusion of low taxes.

The Canada Health Act and Canada Health Transfer

The federal Canada Health Act sets the standards for all provinces and requires coverage for all necessary care provided in hospitals and by physicians. But health care is ultimately the responsibility of the province.

General revenues from the Federal Government provide funding for health care to the provinces and territories through the Canada Health Transfer (CHT). Up until this past year, the CHT consisted of two components: a cash transfer and a tax transfer. Though CHT is allocated on a per capita basis, the cash transfer was not. Instead, the CHT cash transfer would take into account the value of provincial and territorial tax points and the fact that provinces do not have equal economies and, therefore, have unequal capacity to raise tax revenues. This meant that provinces with the highest revenue raising ability received lower per capita CHT cash payments than other provinces.

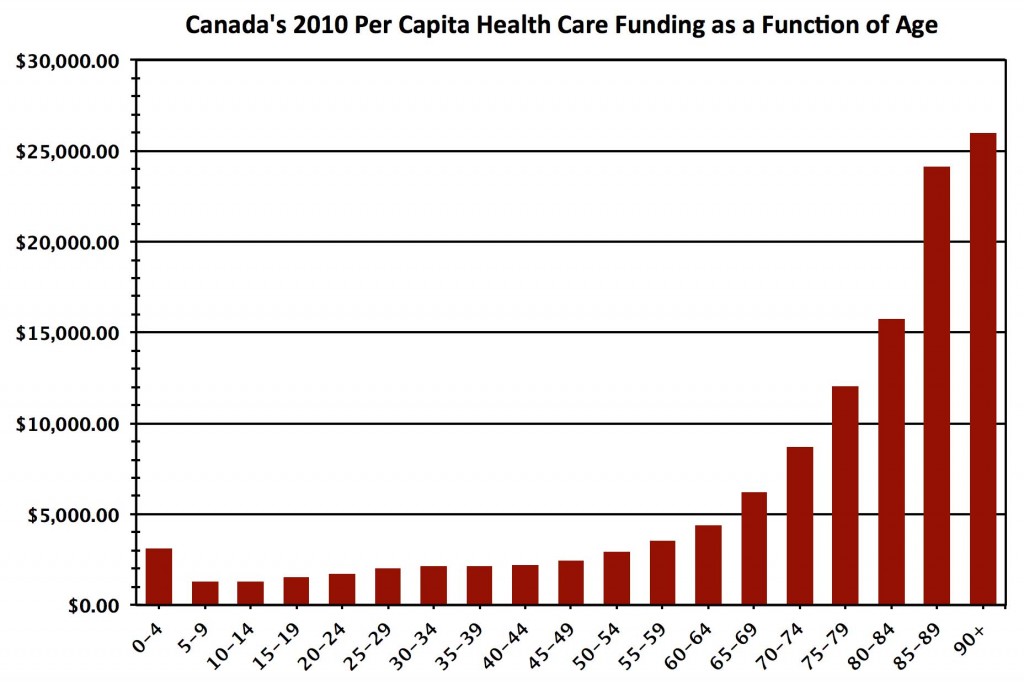

However, since January 2014, CHT allocations are now determined solely on an equal per capita cash basis. While this new system means that all provinces will receive equal transfer payments based on population size, I believe that this is not the most equitable way to proceed, particularly in light of provincial age demographics and associated health care costs. Take for example BC, a province many view as a popular retirement destination. It is common practice for individuals who have lived and worked – and therefore paid taxes – elsewhere, to move to BC later in life. However, with national trends showing that seniors’ health care costs more than that of any other age group, this can put a significant strain on our provincial health care system — one that cannot afford to go unaccounted for (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Per capita funding of health care as a function of age. Note that as age increases, health care costs increase dramatically. Annually, more than $25,000 is spent on health care costs for a Canadian over the age of 90. Source: Canadian Institute for Health Information, National Health Expenditure Trends, 1975 to 2012.

Figure 1: Per capita funding of health care as a function of age. Note that as age increases, health care costs increase dramatically. Annually, more than $25,000 is spent on health care costs for a Canadian over the age of 90. Source: Canadian Institute for Health Information, National Health Expenditure Trends, 1975 to 2012.

Let’s unpack this further. In the 2014-15 budget year, the Federal Government Canada Health Transfer amounted to 32.1 billion dollars distributed across all provinces. In 2014 Canada’s population was estimated to be 35,540,400, and British Columbia’s population was estimated to be 4,631,300. Alberta has a similar population to that of British Columbia (see Table below).

| Province | Population | Ages 0-14 | Ages 15-64 | Ages 65+ |

| Alberta | 4,121,700 | 18.3% | 70.4% | 11.3% |

| BC | 4,631,300 | 14.6% | 68.4% | 17.0% |

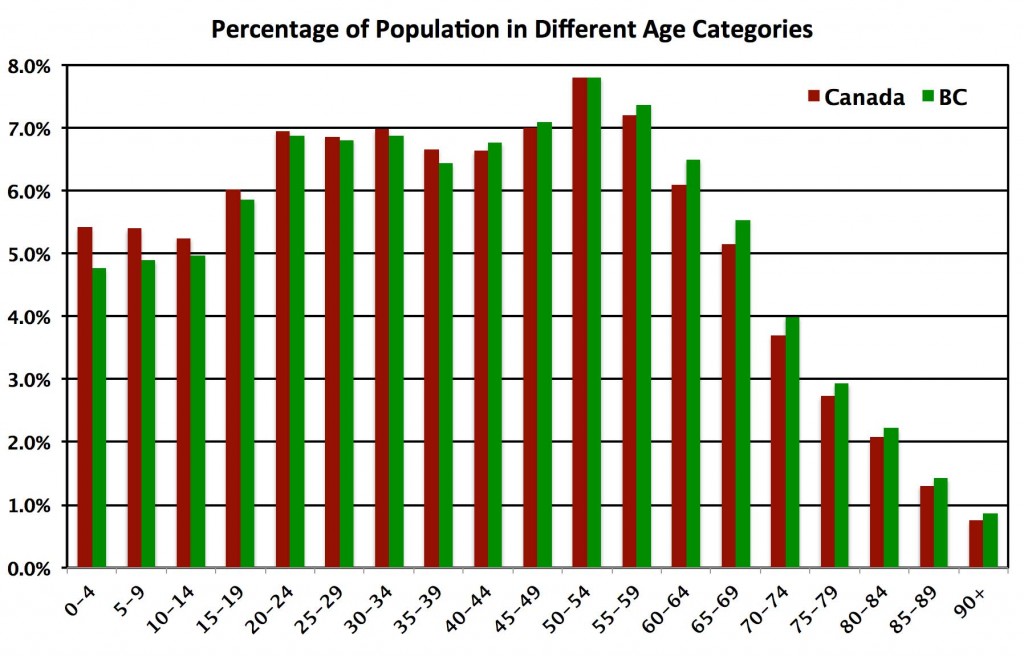

As clearly evident in Figure 2, British Columbia had a smaller percentage of its population in every age group under the age of forty than the Canadian average. The opposite is true for those over the age of forty. Compared to Alberta, British Columbia is home to nearly 70% more seniors. A quick glance back at Figure 1 immediately highlights the glaring inequity in the fixed CHT dollar per person transfer formula. British Columbia has a higher proportion of seniors than the rest of Canada and it is this age demographic that requires more health services. The funding should reflect the actual cost of service delivery.

Figure 2: Percentage of overall population in separate age categories for Canada (Red) and British Columbia (Green). Note that the percentage of overall population under the age of 40 is greater in Canada in a whole than in British Columbia. The reverse occurs over the age of 40 when health care costs per capita start to increase. Source: BC Stats and Statistics Canada.

Figure 2: Percentage of overall population in separate age categories for Canada (Red) and British Columbia (Green). Note that the percentage of overall population under the age of 40 is greater in Canada in a whole than in British Columbia. The reverse occurs over the age of 40 when health care costs per capita start to increase. Source: BC Stats and Statistics Canada.

It’s a relatively straightforward calculation to weight the CHT transfer to each province by its age demographic and associated health care delivery cost. Rather than receiving 13.0% ($4.183 billion) of the total CHT funding (reflecting 13.0% of Canada’s population residing in British Columbia), we should receive 13.5%. While this may not seem like a lot, it translates into 153 million dollars that British Columbia must find from other sources.

Nevertheless, no matter the method that CHT payments are allocated, these federal transfers only cover a portion of BC’s annual healthcare expenditures. The remaining expenses are financed out of general revenues raised by tax and non-tax sources, with MSP premiums presently contributing over $2 billion per year.

Alternatives to MSP Premiums

While here in BC we do not have the fiscal resources to stop charging MSP premiums without replacing the revenues, there are alternative, and more progressive, options we could be exploring. We need look no further than provinces like Ontario and Quebec, where health premiums are paid through personal income tax systems, rather than flat-rate levies. This approach avoids the regressive effects of monthly premiums, as rates rise with income to a maximum annual level. For example, in Ontario the current maximum annual rate is set at $900 for taxable incomes of $200,600 and higher, with those individuals earning less than $20,000 paying no premiums, and in Quebec the maximum annual contribution is $1,000 for taxable incomes over $150,000. At the same time the British Columbia government should lobby for its fair share of CHT revenue — a share that reflects our demographics and the actual cost of delivering health services.

It is time for BC to replace MSP premiums with a more progressive and equitable approach to financing our health care system. Whether this means following in the steps of Ontario and Quebec with an income tax-based approach, or simply raising other taxes, such as corporate tax rates, as the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) found after conducting extensive research on what British Columbians think about taxes:

“[British Columbians] know more revenues are required if we are going to tackle the major challenges we face, like growing inequality and persistent poverty, climate change, and the affordability crisis squeezing so many families. And we know higher revenues are needed to sustain and enhance the public services…In short, [we] are ready for a thoughtful, democratic conversation about how we raise needed revenues and ensure everyone pays a fair share.”

5 Comments

There is no nurse shortage….LPNs can do the job and save money…

http://www.ipetitions.com/petition/lpns-not-being-used-to-alleviate-nursing-shortage/?utm_medium=social&utm_source=facebook&utm_campaign=button

I have a couple of issues with what you state here. First you state sales tax is regressive as it does not differentiate between incomes, this is incorrect in the manner that those with more disposable income spend more thus pay more in sales taxes. Second the point on income for map premiums that nobody emphasizes is that it is net income not gross income. Another point I would like to bring to attention is that BC is the only province that has a large increase in retired people in the country. This to me is an issue as to the fact that they paid all their taxes to another province but use BC’s medical resources with their only contribution being the MSP. What do you as a politician propose to do to make this more fair if you want to remove the MSP? Also what is your position on the disparity of government input between federal and provincial governments?

Hello Jim, the BC government (and I would if the BC Greens were government) needs to speak out strongly against the unfair nature of the CHT as I mentioned in the article. To be blunt, tying the CHP to GDP makes no sense. Frankly the only reason I can see why the BC Liberals did not speak our strongly against this when the Harper Tories brought it in was that they would have to publicly admit that their LNG plans were nothing but a pipedream (which of course they are).

I just happened to find your comments about changing the MSP to a progressive tax similar to the one in Ontario. I heartily agree.

Having recently moved to Victoria from Toronto I was somewhat annoyed by the MSP premium idea. Surely the administration costs to collect and process such a system must be considerable. Whereas a Provincial tax not only allows for a sliding scale based on income, but is a fairer system especially if one has a scale comprised of many levels instead of just two.

Keep up the good work.

Thank you for raising this important issue for all British Columbians. I live in John Horgan’s constituency. I have been annoyed for some time about the MSP billings I get monthly and in early December 2014 (not knowing what you were up to) I emailed my MLA to ask: 1) his opinion about whether this violated the Canada Health Act, in principle or legally, and 2) what his and the provincial NDP’s position was on the matter. I expected a quick and easy response. Now two months later I have yet to get an answer. Two days ago I was told that my email has been sent to the NDP Health critic for a response.

Your approach and analysis has filled the vacuum. That’s good leadership!