British Columbia’s Family Doctor Shortage

With over 4.5 million Canadians in need of a family physician, Canada appears to be facing the largest doctor shortage since the creation of Medicare in 1968. Our practicing physician to patient ratio landed us 17th out of 21 in a 2006 OECD report on physician services and the situation hasn’t improved since – despite being the focus of many political promises.

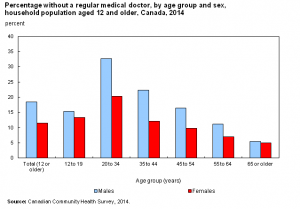

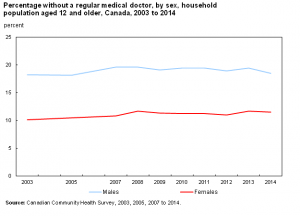

Figure 1: Percentage of Canadians without a family doctor by age, group and sex aged 12 and over. a) For various age groups; b) Averaged 0ver all ages. Data from Statistics Canada.

Over the last few years, the B.C. Liberals have repeatedly vowed that every British Columbian would have a family doctor by 2015. In 2010 then Health Services Minister Kevin Falcon announced that the Province was going to overhaul its primary health-care system with a $137-million investment to “strengthen service delivery, ensure patients are full participants in their care and provide every British Columbian who wants a family doctor with one by 2015.”

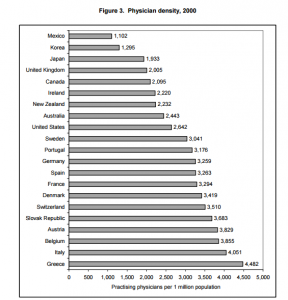

Figure 2: Practicing physicians per one million population for several countries. Repropduced from the OECD report: The Supply of Physician Services in OECD Countries.

In February of 2013 the BC Liberals renewed their commitment with the $132.4 million ‘A GP for Me’ pilot program they said would ensure everyone who wanted a family doctor would be able to access one within two years.

“The objective is clear, all British Columbians will have access to a family physician…” Unfortunately, 2015 has come and gone and there are an incredible number of people still in need of a family doctor.

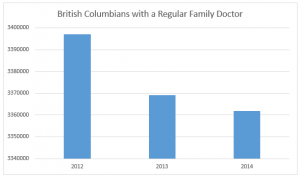

In fact, fewer British Columbians have a regular doctor now than before the government made those lofty promises. According to Statistics Canada, in 2012 3,397,007 people in BC had a family doctor. By 2013 that number had fallen by 27,947 to 3,369,060. In 2014 it was lower still at 3,361,856.

In fact, fewer British Columbians have a regular doctor now than before the government made those lofty promises. According to Statistics Canada, in 2012 3,397,007 people in BC had a family doctor. By 2013 that number had fallen by 27,947 to 3,369,060. In 2014 it was lower still at 3,361,856.

Despite the incredible amount of money that has been thrown at this problem, today in British Columbia it is estimated that over 200,000 people are still actively looking for a family doctor.

When facing a problem of this magnitude and complexity, it is important to look back at the policies and regulations that got us here. While there are no doubt countless contributing factors that influence doctor shortages, what follows is an overview of the major changes that shifted our course towards one critically deficient in family physicians.

In 1961, the average medical ratio in BC was 758 patients for each doctor. Much like today, however, the rural-urban distribution of doctors was uneven. In rural areas the ratio was much higher, at 1,229 patients per doctor, and 73.6% of the province’s physicians were concentrated in Vancouver and Victoria.

Sensing problems ahead, the federal Royal Commission on Health Services (who outlined the foundation for Canada’s universal medicare system) analyzed the medical workforce statistics and predicted an overall shortage of doctors by the 1970’s (source available in hard copy only, page 246). Along with increasing med-student intake at universities across the country, the report recommended the establishment of at least four additional medical schools to meet the needs of a growing population. Their shortage projections extended until 1991 (page 70).

When 1991 arrived, however, the perceived supply of doctors did a rapid reversal. A report presented to the Federal/Provincial/Territorial Conference of Deputy Ministers of Health by Barer and Stoddart cautioned that we were, in fact, heading towards a doctor surplus. Public policy shifted accordingly and drastic changes were made to the way physicians were trained and licensed in Canada.

Barer and Stoddart were concerned that there were too many doctors, especially in urban areas, and that this would put people at risk of being over-treated as physicians (who bill per patient) competed for limited cases (page 11, 48-50). This theory of “physician-induced demand,” it should be noted, has always been a controversial and inconclusively proven phenomenon (page 19). Nevertheless, Barer and Stoddart recommended limiting med school entry and reducing the use of foreign-trained physicians and governments followed suite.

In BC, the government introduced a combination of incentives and penalties in the hopes of shifting more doctors away from city centers and into remote areas. By 1993, travel assistance, isolation allowance, and subsidized, salaried positions were offered to doctors willing to move to more rural locations. At the same time, the government tried to manage doctors as they prepared to enter or exit the workforce. Young doctors looking to set up practices in areas deemed “oversupplied” were met with a 50 per cent reduction in their fee-for-service rate. This penalty only lasted a few years though, as it was challenged by physicians and the Professional Association of Residents of British Columbia and in 1997 ruled unconstitutional by the BC Supreme Court. The Court deemed the fee penalty imposed on urban doctors as a violation of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guaranteed mobility and equity clause, as well as a breach of Canada Health Act’s requirement for reasonable compensation for insured services (page 24). Mandatory retirement caps set at 75 year were removed as well, following a legal challenge by the Senior Physician Society of BC (page 25).

A few years later, however, opinions had shifted yet again and the public and policy makers were back to being worried about a serious national doctor shortage. Incredibly, within a span of a decade the believed supply of doctors had done a complete reversal. A 2002 report for the Canadian Institute for Health Information, From Perceived Surplus to Perceived Shortage: What happened to Canada’s Physician Workforce in the 1990s?, cited changes to postgraduate medical training programs as the largest contributing factor. By extending the residency requirement for general practitioners there was an extra delay on new doctors entering the workforce. In addition, a higher proportion of medical students elected to specialize, further limiting the number of family doctors (page 36). At the same time more doctors were retiring, fewer students were being accepted to medical school, and the number of positions available to foreign-train doctors dropped – all while the general population continued to increase and get proportionally older.

Five years after the BC government was taken to court for reducing urban doctors billing rates they were back to offering generous financial incentives. Retention Allowances were introduced in 2002 to encourage doctors to start practices in smaller communities. The Northern and Isolation Travel Assistance Outreach Program covered travel costs and accommodation for physicians service isolated communities. In 2007 the Family Physicians for British Columbia program paid $100,000 to doctors willing to establish full service practices for at least three years in underserved areas. That year not one doctor stepped forward to accept any of the 15 Interior Health incentive packages.

Picking up on research that suggests medical students recruited from rural backgrounds are more likely to work in non-urban areas after graduating, the BC government announced plans to expand and upgrade teaching hospitals around the province. They also increased province wide first-year enrollment from 128 in 2001 to 256 in 2007 and authorized the creation of three additional medical campuses at UVic, UNBC, and UBC Okanagan.

Backtracking on foreign-trained doctor restrictions, International Medical Graduates were once again seen as part of the solution to physician shortages across Canada. Canada has never trained enough physicians to meet the country’s needs and foreign-trained doctors account for roughly a quarter of the medical workforce in Canada. Though securing a position is incredibly competitive for non-Canadian doctors, they do account for roughly 38% of Newfoundland and Labrador’s physicians and 46% of Saskatchewan’s. Unsurprisingly, the logistics of integrating and licensing foreign-trained physicians are clumsy and slow, though some medical colleges are recognized as accredited and approved by the College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia which streamlines applications.

In 2007 the college was licensing 100 to 150 foreign doctors per year and in the 2008 Speech from the Throne the BC government promised that a “new framework to allow Canadian citizens trained outside of Canada to find residencies and practices in B.C. [would] be developed and implemented.”

This included a new health profession review board to “ensure that all qualified health workers can fully and appropriately utilize the training of skills and not be denied that right by unnecessary credentialing and licensure restrictions.”

Bill 25, the Health Professions (Regulatory Reform) Amendment Act, introduced in April of the same year provided the legislative structure for these changes

Despite these initiatives the practice of importing doctors is not without controversy and many jurisdictions are trying to become less dependent on them. In 2001 the High Commissioner to South Africa asked Canada to stop depleting the supply of doctors in his country where hospitals were desperately underserved. “Immigration of doctors can ease physician shortages in countries where numbers are lacking but it raises difficult questions about international equity when there are net, long-term flows of physicians from poorer countries with low average health status to richer countries with high health status,” writes Simoens and Hurst’s report on the supply of physicians in OECD counties. “As a result, many OECD countries aim for self-sufficiency in physician supply.”

One possible alternative to the geographically uneven distribution of doctors in BC is the use of “Telehealth” services which use videoconferencing technologies to connect doctors and patients. There are concerns about privacy and insurance coverage with these systems, but the presence of nurses to facilitate calls and operate examination cameras on the patient side do make them feasible in certain scenarios.

The certification of more nurse practitioners is also seen as a promising way to increase patient care while reducing relative health care costs. Nurse practitioners were first regulated in BC in 2005, not as a substitute for doctors, but a compliment. When paired with doctors they can streamline patient care by treating routine illnesses and injuries while physicians handle more complex diagnoses. Nurse Practitioners are able to diagnose, consult, order and interpret tests, prescribe, and treat health conditions. They work in both independent and collaborative practice roles across BC and practice acute care, outpatient clinics, residential care and community settings.

Now at the start of 2016, we find ourselves once again repeating history as we offer doctors a patchwork of financial incentives in an attempt to meet the province’s growing medical needs.

Currently, in addition to recruitment incentives ($15,000 or $20,000), relocation incentives ($15,000), the rural retention program, isolation allowance, and various other training bursaries, rural physicians receive a one-time payment of $100,000 for a commitment to work for three years in a designated rural communities. The incentive is available to family practitioners, specialists and residents who are paid $50,000 when they start work in the community and the remaining $50,000 after one year.

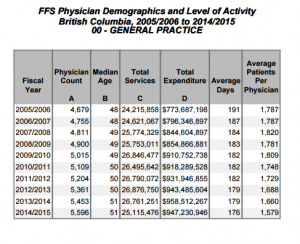

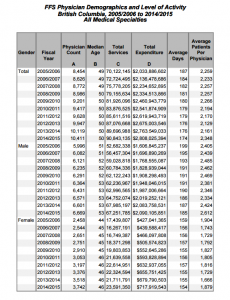

In some situations these economic bonuses have changed the problem, without improving the overall situation. The current set up gives doctors the ability to work less while earning more, and one can hardly fault them for making the most of it. As the graphs from the MSP Physician Resource Report below indicate, the total expenditure for general practice doctors has increased significantly since 2005, but the average number of patients treated per physician has dropped. The government’s policy changes over the last ten years have lead to more doctors, working less days, treating fewer patients. An important, though further complicating, caveat to this data is that it focuses on quantity of care – not quality. In many cases doctors seeing fewer patients is a positive change as it indicates they are spending more time with each individual. For people struggling with multiple or complex conditions this added assistance is essential.

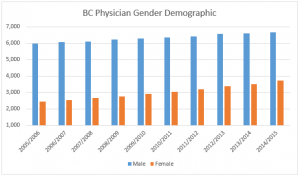

With more female doctors, who statistically allocate more time to each patient, practicing in BC than ever before and doctors in general striving to create a healthier work life balance, the policies used to influence the doctor shortages of the 1970’s are no longer relevant. Family doctors play a vital role in our well being and they deserve a policy framework that lets them treat patients in a manageable, fulfilling, and efficient manner.

With more female doctors, who statistically allocate more time to each patient, practicing in BC than ever before and doctors in general striving to create a healthier work life balance, the policies used to influence the doctor shortages of the 1970’s are no longer relevant. Family doctors play a vital role in our well being and they deserve a policy framework that lets them treat patients in a manageable, fulfilling, and efficient manner.

Given this province’s complicated history with doctor shortages, what is most concerning about the BC Liberal’s promise to provide every British Columbian with a family physician is not that they have failed – one only has to look back at the struggles Canada has had maintaining an appropriate number of GPs to know BC’s doctor shortage was never something that could be fixed in two years. What is most concerning is that British Columbians were repeatedly mislead about what could be realistically achieved.

We’re beginning to see a pattern emerge with this government. Whether it be promises of 100,000 LNG jobs, a debt free BC, or a GP for every British Columbian, the government is long on rhetoric and short on policy grounded in evidence. British Columbians deserve better. They deserve a government that is transparent and honest with its expectations and promises.

Over the next year, and in collaboration with my policy advisors, I will be outlining ways we might consider to alleviate the British Columbia’s GP crunch.

If you have ideas you would like to share with me and my team, please don’t hesitate to email us at: Andrew.Weaver.MLA@leg.bc.ca

3 Comments

Thank you for drawing attention to this issue once again. I just finished writing a letter on the topic to Terry Lake which I’m including here. Do you have any suggestions on who else I should write to or what else I should do about this?

> Dear Mr. Lake, I have been living in Victoria, British Columbia for almost my whole life and have always had a family doctor. Very recently my family doctor retired and I now find myself, like many other people in Victoria and the rest of BC, without a family doctor. When I went to the College of Physicians and Surgeons website to look for a new doctor, I found that NONE are available in Victoria. Back in July 2015 in a CBC news article where you and Dr. Cavers are interviewed, a statement was made that the “BC Doctors and the Health Ministry were working together to solve the shortage.” At that time, there were still three doctors taking patients and now there are none. I understand that this is a difficult issue to solve if you are continuing to rely on only doctors to supply medical help. I’m wondering why Nurse Practitioners are not playing a bigger role in alleviating this problem. I would be happy to have a Nurse Practitioner provide me with my medical care but there are very few places where they are employed and I can’t find a listing of where they work anywhere. I’m sure using Nurse Practitioners would not only be a cost effective solution but provide the help that the people of BC so desperately need.

> Please act now as this problem has become a crisis.

>

> Yours truly,

>

> Debbie Marchand

I think you’ll find that “Braer and Stoddart” is actually Morris Barer of UBC.

Thank you for this. We’ve corrected it.