Celebrating Local Businesses in Our Community – Victoria Eye

Dr. Olivia Dam cheerfully handed my colleagues and me hairnets and booties before leading us into the operating area. In the middle of the first room sat a very large laser. We were in a building not far from my constituency office, taking a tour of Victoria Eye and learning more about the services they offer our community.

Dr. Olivia Dam cheerfully handed my colleagues and me hairnets and booties before leading us into the operating area. In the middle of the first room sat a very large laser. We were in a building not far from my constituency office, taking a tour of Victoria Eye and learning more about the services they offer our community.

The impressive piece of machinery in front of us was a Femtosecond refractive laser, Dr. Dam told us, which she uses to perform cataract surgeries. It is the latest technological advancement in the field, allowing her to make a precise 4.9 millimeter capsulotomy incision into the eye and softening the cataract in less than a minute. Dr. Dam assured the more squeamish members of my team (i.e. me) that she uses local anesthesia and a suction-based docking station to keep the eye still and pain free throughout the procedure. “If there is anything that can make the surgery better for the patient, we use it,” Dr. Dam said. “We keep up to date with the very latest technological advancements.”

Victoria Eye was the first facility in Western Canada to receive a consignment of the most progressive extended range lenses available and is the only eye center on Vancouver Island with a Femtosecond refractive laser for refractive cataract surgery. Because these advancements are not classified as medically required to complete cataract surgery, however, they are not insured.

Victoria Eye was the first facility in Western Canada to receive a consignment of the most progressive extended range lenses available and is the only eye center on Vancouver Island with a Femtosecond refractive laser for refractive cataract surgery. Because these advancements are not classified as medically required to complete cataract surgery, however, they are not insured.

From the surgery center we head past the entirely sterile “clean room” and into the recovery room where a row of curtain separated beds (all empty that day) line the wall. Dr. Dam brings out a silver tray to show us the instruments used during eye surgeries.

Watching Dr. Dam’s steady hand demonstrate how she uses each tiny instrument was fascinating. Because their facility is not located in a hospital, each of the five doctors who work at Victoria Eye are trained in advanced life support. Thankfully those skills are rarely if ever needed, but if anything were to come up every patient is in very good hands.

Watching Dr. Dam’s steady hand demonstrate how she uses each tiny instrument was fascinating. Because their facility is not located in a hospital, each of the five doctors who work at Victoria Eye are trained in advanced life support. Thankfully those skills are rarely if ever needed, but if anything were to come up every patient is in very good hands.

Dr. Dam is a comprehensive ophthalmologist specialized in managing medical and surgical ocular problems. She did her medical degree and ophthalmology specialization at Queen’s University in Ontario before completing five years of surgical residency. She has participated in medical service and ophthalmological trips to South Africa, Mozambique, Malawi, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Columbia, South East Asia, India and Bolivia. She moved to Victoria in 2005 and has been caring for patients here ever since.

Dr. Dam is a comprehensive ophthalmologist specialized in managing medical and surgical ocular problems. She did her medical degree and ophthalmology specialization at Queen’s University in Ontario before completing five years of surgical residency. She has participated in medical service and ophthalmological trips to South Africa, Mozambique, Malawi, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Columbia, South East Asia, India and Bolivia. She moved to Victoria in 2005 and has been caring for patients here ever since.

As Vancouver Island’s demographic continues to age the demand for eye care is going to greatly increase. The Victoria Eye center was built anticipating this shift and they are prepared to ramp up care to meet the need. They have capacity for eight doctors, maybe more as many split their time with the hospital.

Collaborating with different eye specialists in one center, Dr. Dam explains, allows them to share expertise, consultations, and the cost of cutting edge equipment. Staying current with the latest technological advancements is far from cheap, Dr. Dam said, but they invest in whatever will make procedures more efficient, effective, and pain-free for their patients. Victoria Eye has been a multi-million dollar project that is ongoing as continues to invest in new technologies to optimize patient care.

Collaborating with different eye specialists in one center, Dr. Dam explains, allows them to share expertise, consultations, and the cost of cutting edge equipment. Staying current with the latest technological advancements is far from cheap, Dr. Dam said, but they invest in whatever will make procedures more efficient, effective, and pain-free for their patients. Victoria Eye has been a multi-million dollar project that is ongoing as continues to invest in new technologies to optimize patient care.

Some types of extended benefits cover surgeries done at their center, but some people also chose to pay out of pocket for the latest and greatest. The Symfony Extended Range lens can cost a few thousand dollars per eye, but Dr. Dam says many people are willing to invest in the new technology because unlike traditional multifocal lenses it allows you to focus within near, intermediate and distance ranges, it doesn’t cause halos or glare, and is especially good for patients with presbyopia.

Some types of extended benefits cover surgeries done at their center, but some people also chose to pay out of pocket for the latest and greatest. The Symfony Extended Range lens can cost a few thousand dollars per eye, but Dr. Dam says many people are willing to invest in the new technology because unlike traditional multifocal lenses it allows you to focus within near, intermediate and distance ranges, it doesn’t cause halos or glare, and is especially good for patients with presbyopia.

Whatever patient’s condition or ability to pay privately, Dr. Dam and her colleagues aim to provide Victoria with the best possible eye care. They have the capacity to treat urgent issues right away, vision surgeries can be done within a few weeks, and the waitlist for the treatment of less serious chronic conditions is rarely longer than a few months.

At the end of the tour we head back through the main hall and stop to look at the incredible series of paintings hanging along the wall. The artists are students from local schools, Dr. Dam tells us. I have no doubt their work will be admired and appreciated by everyone who walks through that hall, but even more so by patients with renewed vision.

At the end of the tour we head back through the main hall and stop to look at the incredible series of paintings hanging along the wall. The artists are students from local schools, Dr. Dam tells us. I have no doubt their work will be admired and appreciated by everyone who walks through that hall, but even more so by patients with renewed vision.

Celebrating Local Businesses in Our Community – Clean Air Yard Care

Barry McLean, a fourth generation farmer from a Manitoban town of 300, moved to Victoria eight years ago to care for his mother. He wasn’t necessarily planning on staying, but he has since married and started a business, so the rest is history, so to speak. I had heard that Barry was making incredible advancements in his zero emission landscaping and gardening ventures here in Victoria and I was keen to learn more about his innovative business.

Barry McLean, a fourth generation farmer from a Manitoban town of 300, moved to Victoria eight years ago to care for his mother. He wasn’t necessarily planning on staying, but he has since married and started a business, so the rest is history, so to speak. I had heard that Barry was making incredible advancements in his zero emission landscaping and gardening ventures here in Victoria and I was keen to learn more about his innovative business.

He started Clean Air Yard Care in 2010 inspired by his grandparents who practiced advanced organic farming techniques for 75 years. Earlier that year he had been redoing the landscaping in his front yard to include more native and drought resistant plants. After the fourth neighbour stopped by to admire his work, saying “you should go into landscaping!” he decided to give the idea some serious thought.

“Looking at the industry in Victoria,” he said, “there are a lot of guys who have just thrown a mower in the back of their truck. But I’ve never been much of a follower so I looked for an underserved niche.” Caring for the environment is a family tradition, Barry told me, building his business based on those values was a given.

“Looking at the industry in Victoria,” he said, “there are a lot of guys who have just thrown a mower in the back of their truck. But I’ve never been much of a follower so I looked for an underserved niche.” Caring for the environment is a family tradition, Barry told me, building his business based on those values was a given.

What if he created a zero emissions lawn and yard care business, powered by solar energy that made no pollution and no noise? Not wanting to do anything half way, he decided to build a solar trailer that could power all of his equipment. The trailer has four solar panels (the complete unit is worth nearly $30,000) that feed DC power inside into a battery bank which is then converted to AC power. With that, Canada’s first zero emission yard care company was born. Even on a cloudy day, Barry told me, his solar trailer can run for weeks. If needed, he can plug it in and bulk charge the battery, but he has only needed to do that twice in the last two years.

What if he created a zero emissions lawn and yard care business, powered by solar energy that made no pollution and no noise? Not wanting to do anything half way, he decided to build a solar trailer that could power all of his equipment. The trailer has four solar panels (the complete unit is worth nearly $30,000) that feed DC power inside into a battery bank which is then converted to AC power. With that, Canada’s first zero emission yard care company was born. Even on a cloudy day, Barry told me, his solar trailer can run for weeks. If needed, he can plug it in and bulk charge the battery, but he has only needed to do that twice in the last two years.

Barry has a few residential clients, though appreciates the year round contracts found with strata and commercial contracts. His team has expanded to include more landscapers and a horticulturist, which he said are a huge assets to their company. They can advise clients on plant care and help them incorporate drought resistant or native plants into their garden.

The cumulative environmental impact of yard care in Canada is huge. Barry explained how a gasoline powered lawn mower emits about 106 lbs of greenhouse gases in one season. “They are very inefficient. Running an old lawn mower for an hour, for example, can produce as much air pollution as driving a new car 550 kilometers.” In addition, Barry continued, the impact of air, ground, and noise pollution associated with yard care in our communities is immense. He argued that “5 percent of Canada’s annual greenhouse gas emissions come from landscaping, not accounting for waste, and the sound of gasoline landscaping equipment can lead to hearing loss and increased anxiety in people nearby.”

The cumulative environmental impact of yard care in Canada is huge. Barry explained how a gasoline powered lawn mower emits about 106 lbs of greenhouse gases in one season. “They are very inefficient. Running an old lawn mower for an hour, for example, can produce as much air pollution as driving a new car 550 kilometers.” In addition, Barry continued, the impact of air, ground, and noise pollution associated with yard care in our communities is immense. He argued that “5 percent of Canada’s annual greenhouse gas emissions come from landscaping, not accounting for waste, and the sound of gasoline landscaping equipment can lead to hearing loss and increased anxiety in people nearby.”

Despite the serious drawbacks of conventional landscaping techniques (gasoline, oil, noise) people seem to resist altering their behaviour. “People get entrenched in the way they do things. The landscapers, but also the people who hire them don’t want to change,” Barry told me. “It comes down to the dollar. People will recycle and use organic fertilizer, but they won’t invest more… They just keep doing things the old way.”

Even when you focus on the dollar, however, Barry’s services are comparable to traditional landscapers. He charges $50 per labour hour, usually working out to around $150 to $200 per month in the summer. It’s tough being undercut by companies who haven’t made a significant upfront investment like he has with his solar trailer and equipment, but the “rampant greenwashing” in the sector is even more disheartening to him, he said. “Some ‘green’ landscapers drive up to consultations in electric cars and then come back for the job with a truck full of electric equipment that they’ve charged by plugging into the grid the night before.”

Even when you focus on the dollar, however, Barry’s services are comparable to traditional landscapers. He charges $50 per labour hour, usually working out to around $150 to $200 per month in the summer. It’s tough being undercut by companies who haven’t made a significant upfront investment like he has with his solar trailer and equipment, but the “rampant greenwashing” in the sector is even more disheartening to him, he said. “Some ‘green’ landscapers drive up to consultations in electric cars and then come back for the job with a truck full of electric equipment that they’ve charged by plugging into the grid the night before.”

Moving the emission-intensive work behind the scenes or one step removed isn’t enough when it comes to addressing our personal contributions to climate change. There are other effective options, Barry concluded, but you have to be willing to do things differently.

“The other challenge we face,” Barry said, “is that 99% of the purchasing or contract agents give no environmental weight or considerations when evaluating tenders.”

“People need to understand the impact that the gas and noise of their machines have on their neighbours and the environment. They need to know there are alternatives.”

Clean Air Yard Care has been awarded both a Saanich and CRD Eco-Star Award for “Climate Action” and “Green Energy Leadership.” In 2015 Barry was a finalist for the CRD Eco-Star Awards for Eco-Prenuer of the Year.

British Columbia’s Family Doctor Shortage

With over 4.5 million Canadians in need of a family physician, Canada appears to be facing the largest doctor shortage since the creation of Medicare in 1968. Our practicing physician to patient ratio landed us 17th out of 21 in a 2006 OECD report on physician services and the situation hasn’t improved since – despite being the focus of many political promises.

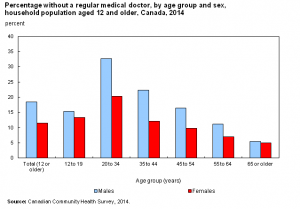

Figure 1: Percentage of Canadians without a family doctor by age, group and sex aged 12 and over. a) For various age groups; b) Averaged 0ver all ages. Data from Statistics Canada.

Over the last few years, the B.C. Liberals have repeatedly vowed that every British Columbian would have a family doctor by 2015. In 2010 then Health Services Minister Kevin Falcon announced that the Province was going to overhaul its primary health-care system with a $137-million investment to “strengthen service delivery, ensure patients are full participants in their care and provide every British Columbian who wants a family doctor with one by 2015.”

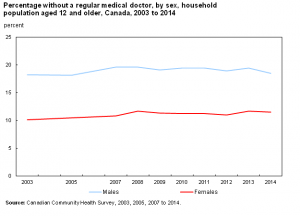

Figure 2: Practicing physicians per one million population for several countries. Repropduced from the OECD report: The Supply of Physician Services in OECD Countries.

In February of 2013 the BC Liberals renewed their commitment with the $132.4 million ‘A GP for Me’ pilot program they said would ensure everyone who wanted a family doctor would be able to access one within two years.

“The objective is clear, all British Columbians will have access to a family physician…” Unfortunately, 2015 has come and gone and there are an incredible number of people still in need of a family doctor.

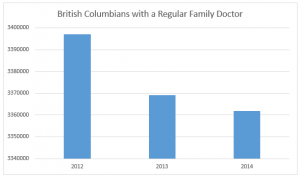

In fact, fewer British Columbians have a regular doctor now than before the government made those lofty promises. According to Statistics Canada, in 2012 3,397,007 people in BC had a family doctor. By 2013 that number had fallen by 27,947 to 3,369,060. In 2014 it was lower still at 3,361,856.

In fact, fewer British Columbians have a regular doctor now than before the government made those lofty promises. According to Statistics Canada, in 2012 3,397,007 people in BC had a family doctor. By 2013 that number had fallen by 27,947 to 3,369,060. In 2014 it was lower still at 3,361,856.

Despite the incredible amount of money that has been thrown at this problem, today in British Columbia it is estimated that over 200,000 people are still actively looking for a family doctor.

When facing a problem of this magnitude and complexity, it is important to look back at the policies and regulations that got us here. While there are no doubt countless contributing factors that influence doctor shortages, what follows is an overview of the major changes that shifted our course towards one critically deficient in family physicians.

In 1961, the average medical ratio in BC was 758 patients for each doctor. Much like today, however, the rural-urban distribution of doctors was uneven. In rural areas the ratio was much higher, at 1,229 patients per doctor, and 73.6% of the province’s physicians were concentrated in Vancouver and Victoria.

Sensing problems ahead, the federal Royal Commission on Health Services (who outlined the foundation for Canada’s universal medicare system) analyzed the medical workforce statistics and predicted an overall shortage of doctors by the 1970’s (source available in hard copy only, page 246). Along with increasing med-student intake at universities across the country, the report recommended the establishment of at least four additional medical schools to meet the needs of a growing population. Their shortage projections extended until 1991 (page 70).

When 1991 arrived, however, the perceived supply of doctors did a rapid reversal. A report presented to the Federal/Provincial/Territorial Conference of Deputy Ministers of Health by Barer and Stoddart cautioned that we were, in fact, heading towards a doctor surplus. Public policy shifted accordingly and drastic changes were made to the way physicians were trained and licensed in Canada.

Barer and Stoddart were concerned that there were too many doctors, especially in urban areas, and that this would put people at risk of being over-treated as physicians (who bill per patient) competed for limited cases (page 11, 48-50). This theory of “physician-induced demand,” it should be noted, has always been a controversial and inconclusively proven phenomenon (page 19). Nevertheless, Barer and Stoddart recommended limiting med school entry and reducing the use of foreign-trained physicians and governments followed suite.

In BC, the government introduced a combination of incentives and penalties in the hopes of shifting more doctors away from city centers and into remote areas. By 1993, travel assistance, isolation allowance, and subsidized, salaried positions were offered to doctors willing to move to more rural locations. At the same time, the government tried to manage doctors as they prepared to enter or exit the workforce. Young doctors looking to set up practices in areas deemed “oversupplied” were met with a 50 per cent reduction in their fee-for-service rate. This penalty only lasted a few years though, as it was challenged by physicians and the Professional Association of Residents of British Columbia and in 1997 ruled unconstitutional by the BC Supreme Court. The Court deemed the fee penalty imposed on urban doctors as a violation of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guaranteed mobility and equity clause, as well as a breach of Canada Health Act’s requirement for reasonable compensation for insured services (page 24). Mandatory retirement caps set at 75 year were removed as well, following a legal challenge by the Senior Physician Society of BC (page 25).

A few years later, however, opinions had shifted yet again and the public and policy makers were back to being worried about a serious national doctor shortage. Incredibly, within a span of a decade the believed supply of doctors had done a complete reversal. A 2002 report for the Canadian Institute for Health Information, From Perceived Surplus to Perceived Shortage: What happened to Canada’s Physician Workforce in the 1990s?, cited changes to postgraduate medical training programs as the largest contributing factor. By extending the residency requirement for general practitioners there was an extra delay on new doctors entering the workforce. In addition, a higher proportion of medical students elected to specialize, further limiting the number of family doctors (page 36). At the same time more doctors were retiring, fewer students were being accepted to medical school, and the number of positions available to foreign-train doctors dropped – all while the general population continued to increase and get proportionally older.

Five years after the BC government was taken to court for reducing urban doctors billing rates they were back to offering generous financial incentives. Retention Allowances were introduced in 2002 to encourage doctors to start practices in smaller communities. The Northern and Isolation Travel Assistance Outreach Program covered travel costs and accommodation for physicians service isolated communities. In 2007 the Family Physicians for British Columbia program paid $100,000 to doctors willing to establish full service practices for at least three years in underserved areas. That year not one doctor stepped forward to accept any of the 15 Interior Health incentive packages.

Picking up on research that suggests medical students recruited from rural backgrounds are more likely to work in non-urban areas after graduating, the BC government announced plans to expand and upgrade teaching hospitals around the province. They also increased province wide first-year enrollment from 128 in 2001 to 256 in 2007 and authorized the creation of three additional medical campuses at UVic, UNBC, and UBC Okanagan.

Backtracking on foreign-trained doctor restrictions, International Medical Graduates were once again seen as part of the solution to physician shortages across Canada. Canada has never trained enough physicians to meet the country’s needs and foreign-trained doctors account for roughly a quarter of the medical workforce in Canada. Though securing a position is incredibly competitive for non-Canadian doctors, they do account for roughly 38% of Newfoundland and Labrador’s physicians and 46% of Saskatchewan’s. Unsurprisingly, the logistics of integrating and licensing foreign-trained physicians are clumsy and slow, though some medical colleges are recognized as accredited and approved by the College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia which streamlines applications.

In 2007 the college was licensing 100 to 150 foreign doctors per year and in the 2008 Speech from the Throne the BC government promised that a “new framework to allow Canadian citizens trained outside of Canada to find residencies and practices in B.C. [would] be developed and implemented.”

This included a new health profession review board to “ensure that all qualified health workers can fully and appropriately utilize the training of skills and not be denied that right by unnecessary credentialing and licensure restrictions.”

Bill 25, the Health Professions (Regulatory Reform) Amendment Act, introduced in April of the same year provided the legislative structure for these changes

Despite these initiatives the practice of importing doctors is not without controversy and many jurisdictions are trying to become less dependent on them. In 2001 the High Commissioner to South Africa asked Canada to stop depleting the supply of doctors in his country where hospitals were desperately underserved. “Immigration of doctors can ease physician shortages in countries where numbers are lacking but it raises difficult questions about international equity when there are net, long-term flows of physicians from poorer countries with low average health status to richer countries with high health status,” writes Simoens and Hurst’s report on the supply of physicians in OECD counties. “As a result, many OECD countries aim for self-sufficiency in physician supply.”

One possible alternative to the geographically uneven distribution of doctors in BC is the use of “Telehealth” services which use videoconferencing technologies to connect doctors and patients. There are concerns about privacy and insurance coverage with these systems, but the presence of nurses to facilitate calls and operate examination cameras on the patient side do make them feasible in certain scenarios.

The certification of more nurse practitioners is also seen as a promising way to increase patient care while reducing relative health care costs. Nurse practitioners were first regulated in BC in 2005, not as a substitute for doctors, but a compliment. When paired with doctors they can streamline patient care by treating routine illnesses and injuries while physicians handle more complex diagnoses. Nurse Practitioners are able to diagnose, consult, order and interpret tests, prescribe, and treat health conditions. They work in both independent and collaborative practice roles across BC and practice acute care, outpatient clinics, residential care and community settings.

Now at the start of 2016, we find ourselves once again repeating history as we offer doctors a patchwork of financial incentives in an attempt to meet the province’s growing medical needs.

Currently, in addition to recruitment incentives ($15,000 or $20,000), relocation incentives ($15,000), the rural retention program, isolation allowance, and various other training bursaries, rural physicians receive a one-time payment of $100,000 for a commitment to work for three years in a designated rural communities. The incentive is available to family practitioners, specialists and residents who are paid $50,000 when they start work in the community and the remaining $50,000 after one year.

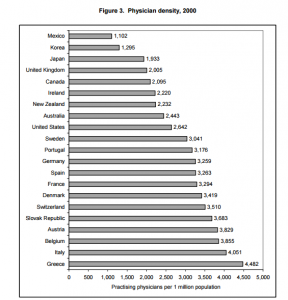

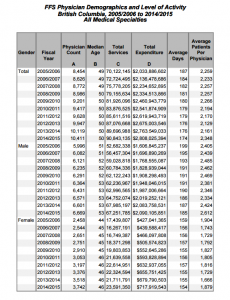

In some situations these economic bonuses have changed the problem, without improving the overall situation. The current set up gives doctors the ability to work less while earning more, and one can hardly fault them for making the most of it. As the graphs from the MSP Physician Resource Report below indicate, the total expenditure for general practice doctors has increased significantly since 2005, but the average number of patients treated per physician has dropped. The government’s policy changes over the last ten years have lead to more doctors, working less days, treating fewer patients. An important, though further complicating, caveat to this data is that it focuses on quantity of care – not quality. In many cases doctors seeing fewer patients is a positive change as it indicates they are spending more time with each individual. For people struggling with multiple or complex conditions this added assistance is essential.

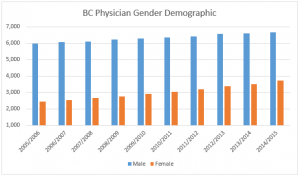

With more female doctors, who statistically allocate more time to each patient, practicing in BC than ever before and doctors in general striving to create a healthier work life balance, the policies used to influence the doctor shortages of the 1970’s are no longer relevant. Family doctors play a vital role in our well being and they deserve a policy framework that lets them treat patients in a manageable, fulfilling, and efficient manner.

With more female doctors, who statistically allocate more time to each patient, practicing in BC than ever before and doctors in general striving to create a healthier work life balance, the policies used to influence the doctor shortages of the 1970’s are no longer relevant. Family doctors play a vital role in our well being and they deserve a policy framework that lets them treat patients in a manageable, fulfilling, and efficient manner.

Given this province’s complicated history with doctor shortages, what is most concerning about the BC Liberal’s promise to provide every British Columbian with a family physician is not that they have failed – one only has to look back at the struggles Canada has had maintaining an appropriate number of GPs to know BC’s doctor shortage was never something that could be fixed in two years. What is most concerning is that British Columbians were repeatedly mislead about what could be realistically achieved.

We’re beginning to see a pattern emerge with this government. Whether it be promises of 100,000 LNG jobs, a debt free BC, or a GP for every British Columbian, the government is long on rhetoric and short on policy grounded in evidence. British Columbians deserve better. They deserve a government that is transparent and honest with its expectations and promises.

Over the next year, and in collaboration with my policy advisors, I will be outlining ways we might consider to alleviate the British Columbia’s GP crunch.

If you have ideas you would like to share with me and my team, please don’t hesitate to email us at: Andrew.Weaver.MLA@leg.bc.ca

Celebrating Local Businesses in Our Community – Maria’s Deli

Strategically scheduling the meeting around lunch time, I was delighted to be back at Maria’s Deli – a staple during our campaign in 2013. Leading up to the last provincial election my campaign office was located across the street from this amazing deli on Shelbourne and Feltham and I credit them with keeping my team well fed and happy throughout every long, busy day. A family focused business, Maria’s Deli was started in 1977 by Maria Pereria and her husband Floyd. Though they both immigrated to Canada from Sao Miguel Portugal, Maria and Floyd didn’t meet until they signed up for the same English class at Vic High.

Strategically scheduling the meeting around lunch time, I was delighted to be back at Maria’s Deli – a staple during our campaign in 2013. Leading up to the last provincial election my campaign office was located across the street from this amazing deli on Shelbourne and Feltham and I credit them with keeping my team well fed and happy throughout every long, busy day. A family focused business, Maria’s Deli was started in 1977 by Maria Pereria and her husband Floyd. Though they both immigrated to Canada from Sao Miguel Portugal, Maria and Floyd didn’t meet until they signed up for the same English class at Vic High.

Their shop has been in the same location for 38 years and though it is now largely run by their daughter Susan Coombs, it hasn’t changed much. When I arrived Susan was behind the counter cheerfully helping an older customer. Switching between speaking English and Portuguese she says, “She has been coming here as long as I can remember!” Her parents opened the deli the year after she was born and she spent much of her childhood here helping out and visiting with customers, officially starting to work for them when she was 14.

Their shop has been in the same location for 38 years and though it is now largely run by their daughter Susan Coombs, it hasn’t changed much. When I arrived Susan was behind the counter cheerfully helping an older customer. Switching between speaking English and Portuguese she says, “She has been coming here as long as I can remember!” Her parents opened the deli the year after she was born and she spent much of her childhood here helping out and visiting with customers, officially starting to work for them when she was 14.

Now Susan works there with her own daughter, who just finished high school. “The people are the most enjoyable part of working here,” they both agree. It shows too, the place is bustling with people greeting one another and chatting as they shop. Two construction workers come in to get lunch, “I’ve been coming here for 20 years!” one of them tells me even though he looks like he’s hardly 30. He helps another customer read the label on a tin of cookies as Susan makes their sandwiches, slicing their choice of meat and cheese from the huge selection in front of them. Amazingly, their lunch costs less than $5.00. There are fridges stacked with 10 kilo rounds of cheese and an incredible variety of olive oil, vinegar, pasta, and meat. A baker from Esquimalt walks in carrying a tray of Portuguese buns on her shoulder, she delivers buns to Maria’s Deli nearly every day, she says. Today she is dropping off 20 dozen.

Now Susan works there with her own daughter, who just finished high school. “The people are the most enjoyable part of working here,” they both agree. It shows too, the place is bustling with people greeting one another and chatting as they shop. Two construction workers come in to get lunch, “I’ve been coming here for 20 years!” one of them tells me even though he looks like he’s hardly 30. He helps another customer read the label on a tin of cookies as Susan makes their sandwiches, slicing their choice of meat and cheese from the huge selection in front of them. Amazingly, their lunch costs less than $5.00. There are fridges stacked with 10 kilo rounds of cheese and an incredible variety of olive oil, vinegar, pasta, and meat. A baker from Esquimalt walks in carrying a tray of Portuguese buns on her shoulder, she delivers buns to Maria’s Deli nearly every day, she says. Today she is dropping off 20 dozen.

Susan and her daughter joke and laugh as they work and another customer proudly tells me they’ve been coming here for years. “Oh and her mother in law too!” Susan says, “We go way back.”

Susan and her daughter joke and laugh as they work and another customer proudly tells me they’ve been coming here for years. “Oh and her mother in law too!” Susan says, “We go way back.”

Maria’s Deli is a wonderful mainstay in this community, feeding generations of families – and campaign teams lucky enough to work nearby.

Endangered Species Management: Caribou versus Wolves

Over the last few months British Columbia’s controversial wolf cull has been the subject of substantial public dialogue. Like most MLAs, I receive ongoing communication from numerous British Columbians questioning the rationale behind the government’s approach. These communications crescendoed when well known singer Miley Cyrus spoke out against the cull and urged her more than 23 million followers to sign a petition. One of the recent communications I received was from a young woman named Katie. She started off her email saying:

“My name is Katie, and I oppose the wolf cull. In school we learned about predator prey relationships. I know you probably won’t care, and that the government will go ahead with it anyway, but please read this…”

I found her email to be a source of inspiration. Despite her apparent cynicism towards politicians she took the trouble to express her concerns to me (even though she is not a constituent). Her email struck a chord. I campaigned on a promise of evidence-based decision-making and giving youth in our society, the generation that will have to live the consequences of the decisions my generation is making, a voice in the legislature. And so Claire Hume and I decided to look at BC’s controversial wolf cull a little more closely. What follows is an extensive analysis of the available literature. Our analysis derived from many hours of discussions with scientists, including wildlife biologists, with expertise in the area. I look forward to your comments.

Is it justifiable to kill one animal in the name of saving another? What if one of those animals is endangered?

Is it justifiable to kill one animal in the name of saving another? What if one of those animals is endangered?

I have always maintained that humans have a moral obligation to prevent endangered species from going extinct, but wildlife management conflicts in which species are pitted against one another are always challenging. For a variety of industrial, social, or budgeting excuses, they are often situations that have been allowed to escalate far past a point of simpler intervention. When you start rationalizing culling one species to protect another you also introduce an ethical element that needs to be considered alongside scientific findings. Let one – or both – of those species become threatened or endangered and your situation becomes immensely worse.

Many ecosystems have been altered so drastically that we can no longer let nature take its course. If we don’t continue to intervene with the mountain caribou crisis we are currently facing in B.C., for example, it will not be long before the remaining herds in the South Selkirk and Peace regions are extirpated. Ideally, our wildlife management system would never let things get this bad. But it happens. And when it does we have no choice but to make tough decisions.

In January I wrote to the Minister of Forests, Lands, and Natural Resource Operations to ask a number of questions regarding the rationale for the wolf cull in the South Selkirk Mountains and the South Peace region. In response Minister Thompson sent me the supporting data that backed up their wolf cull. I read through it and agreed that with 18 caribou left we needed to take immediate and drastic action to ensure as many caribou as possible survived through another breeding season. Since then, the issue has continued to polarize our province with both sides of the debate claiming science. And in many ways, both sides are right. There is supporting evidence that suggests, for certain situations, that culling wolves is an appropriate wildlife management tool. There are also many other studies that conclude that it is an ineffective solution, one that could make the situation even worse while causing a great deal of animal suffering in the process.

So, where do we go from here? We do a literature review of the available relevant research and we have a conversation. We explore the feasibility of other options and try to find a solution that maximizes protection for threatened species while minimizing the harm done to all other animals. Over the last few months my office has been talking to scientists and analyzing data across disciplines, across species, and across the country (across continents in one case) to learn more about endangered species management.

Lessons from the Vancouver Island Marmot

In the late 1990s the Vancouver Island marmot population dropped to 70 members. While clear-cut logging in marmot territory was thought to be the initial and main reason their population numbers were plummeting, the landscape changes also led to increased predation. Between 1995 and 2005 predation by wolves, cougars, and eagles accounted for 80% of marmot mortality. Much like the caribou, habitat destruction was the main catalyst for their decline and wolves moved in to take advantage of the new open landscape. I reviewed the group’s marmot recovery plan and contacted them to ask why predator control has never been a part of their strategy.

Their Executive Director, Viki Jackson, said they tried everything they could think of on Mount Washington in place of culling predators: they collared cougars and brought dogs in to scare them away, had “shepherds” stay with the marmot colonies, put dirty human clothes around to deter predators, put up fences, and used bear bangers. Having people camp with the marmots 24/7 worked well, Jackson said, but the other attempts didn’t do much. At the same time, they started to have success with their captive breeding program. Without their active intervention the Vancouver Island marmot would have likely gone extinct years ago.

When it comes to endangered species management, Jackson said, there will never be consensus but you have to do everything in your power to protect key females when animal numbers drop to extreme lows. You need to get them over the extinction hump and stable enough that other conservation efforts have a chance to help.

While the specifics of this case do not exactly translate to the needs of larger, transient animals like caribou, I found their imaginative approach to crisis species management inspiring. Threatened species in our province are facing very modern difficulties as they try adapt to new stressors and habitats changed by development. Perhaps we should be trying to combat these challenges with equally modern and innovative solutions before defaulting to predator culling, a practice that only targets one aspect of highly complex situations. With this thought I contacted Dr. Adam Ford from the University of Guelph’s Department of Integrative Biology to talk about the use of technology in wildlife research and management.

GPS Management

Global Positioning Systems (GPS) placed on collars, Dr. Adam Ford explained, can be used to pinpoint, with high accuracy, the location of an animal at a given time. It is also possible to track animals and process data almost instantaneously. Knopff and his colleagues, for example, used GPS to track cougar predation to study predator/prey interactions with immediate data retrieval. “Real time monitoring has enormous potential in the fields of wildlife ecology and conservation, especially for at-risk wildlife,” their report states.

With these systems you can monitor the spatial relationship between an animal and a wide variety of geographical features. Data can be collected that orients an animal in relation to specific points (like feeding grounds), linear features (roads, fence lines, fishing nets, etc.) and spatially dynamic features (like a mobile herd of livestock). Given these tracking advancements, and the incredible success scientist and conservation officers have had using them in wildlife management settings, it is hard not to feel hopeful imagining the great potential for their use with woodland caribou in BC. I think it would be worth assessing, for example, the feasibility of attaching GPS’ to select members of threatened caribou herds and their neighbouring wolf packs, as suggested by Dr. Ford. You could outfit caribou and wolves with GPS collars, Dr. Ford explained, and program them with a GSM-linked messaging system that warns managers when wolves, say, are within 1 km of the caribou. The managers could then travel to the coordinates shown in the GSM message, and herd the wolves away with aversive conditioning. That way, intervention is case-specific and the helicopter time is used much more efficiently. They use this method in Kenya with elephants to keep them away from crop fields and refer to it as ‘geofencing‘.

I appreciate comparing elephants to caribou sounds dangerously like an apples-to-oranges tangent, but the success the Save the Elephants organization has had with GPS-based wildlife management is incredible and certainly worth further consideration. Their Geo-fencing program started ten years ago, in the hopes of reducing human-elephant conflicts. “Kimani was the first elephant to be collared and tested under the Geofencing [system]. He became the focus of the Ol Pejeta management due to his considerable skill in breaking expensive fences. In December 2005 he went on a crop-raiding spree that lasted 21 straight nights.”

In phase one of the project they programmed a virtual fence line (or string of coordinates) into the GPS collar worn by the elephant. If the elephant strays out of his designated range – suggesting he is heading towards farms or villages – his collar sends a text message with his exact location to the reserve managers, who can then mobilize and intervene with negative reinforcements before he does too much damage. After only a few months in his GPS collar, Kimani the elephant had stopped breaking fences. Years later, Kimani has still not returned to his crop-stomping ways.

Another breakthrough, which does not relate to caribou but highlights the brilliant potential for innovative wildlife management strategies, was their elephants and bees hypothesis. “Having found that elephants run from the sound of bees, in 2007, we set up a unique beehive fence line in the area to see if they would deter elephants from raiding crops. To test our hypotheses, we geo-fenced several known crop-raiding elephants to see if their behaviour changed once confronted with large concentration of bees. Thanks to the geo-fencing technology, we were able to witness and confirm that bees did in fact deter elephants from crop raiding.”

Elephant-caribou differences aside, the technology is transferable. “The real-time monitoring algorithms presented here for monitoring African elephants (proximity, geo-fencing, movement rate, and immobility) are widely adaptable and applicable to monitor a variety of behaviours across numerous species,” wrote Wall et al.

While there is considerable consensus within the scientific community about the effective use of technology in wildlife management, I have found concerning disagreement about the role of wolves in caribou declines and the impact of culling them. What follows is a literature review of sorts, of the relevant research that has been done on this subject.

Wolf Cull Literature Review

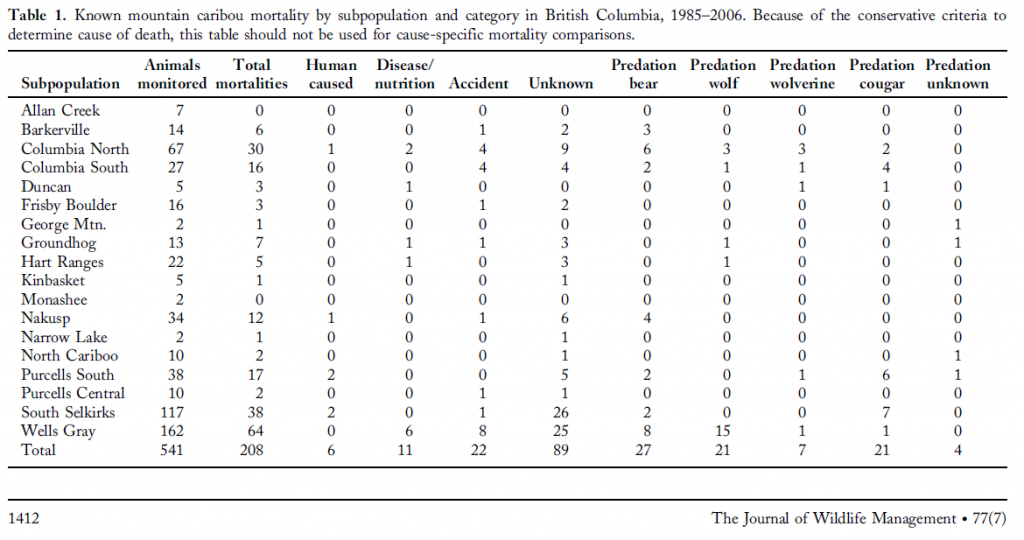

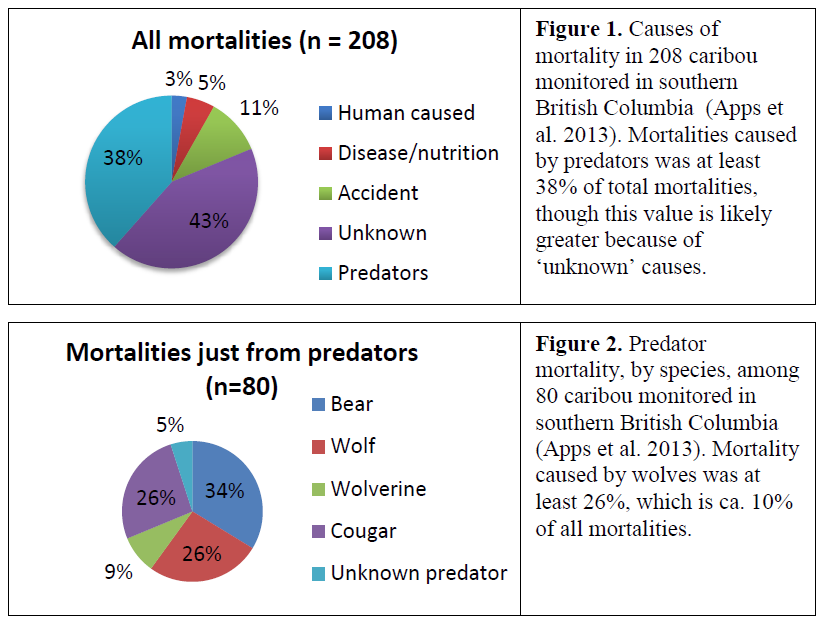

Apps et al. studied the GPS, very high frequency (VHF), and motion sensor data collected from 541 caribou over 22 years. When the collared animals stopped moving for prolonged periods researchers tracked their location and tried to determine the caribou’s cause of death. In their cause-specific mortality analysis of mountain caribou in B.C. they found that wolves are only one of many important sources of mortality for caribou. The data, though limited, indicates that wolves are not necessarily the primary killer of mountain caribou. In fact, it is possible that bears and cougars may have a stronger impact on caribou numbers. That said, I spoke to Dr. Clayton Apps about his study and he cautioned that the data should not generalized too broadly as it pertains to specific sampling cases. The wider conclusion of his work focused on caribou vulnerability as it relates to landscape changes. Wolf predation was found to be concentrated at lower elevations and areas with a higher concentration of roads, which they used as a navigational advantage when hunting.

On a similar theme, DeCesare’s data links industrial development with increased encounters between wolves and caribou, which in turn can lead to increased predation. Supporting that notion, other studies have illustrated the considerable impact wolves can have on local ungulate populations. Kortello et al. conducted a study that analyzed the diet and spatial overlap between wolves and cougars in Banff National Park. During their research they observed a 65% decline in local elk populations following the arrival of wolves. This shift caused cougars to switch from a primarily elk winter diet to one that favoured deer and other alternative prey options.

At this point we have a fairly clear picture of a wolf – caribou relationship that has been knocked out of whack in areas that have been altered by industrial development. Wolves eat caribou, even more so when roads and cleared forests give wolves efficient access to a larger range while simultaneously limiting caribou’s own food sources. If we have too few caribou, and too many wolves, it is easy to conclude a wolf cull would be an appropriate response. Some short term studies support that assumption. Bergerud et al. for example suggested that a wolf cull in Northern B.C. and the Yukon lead to increases in ungulate populations, but many studies do not.

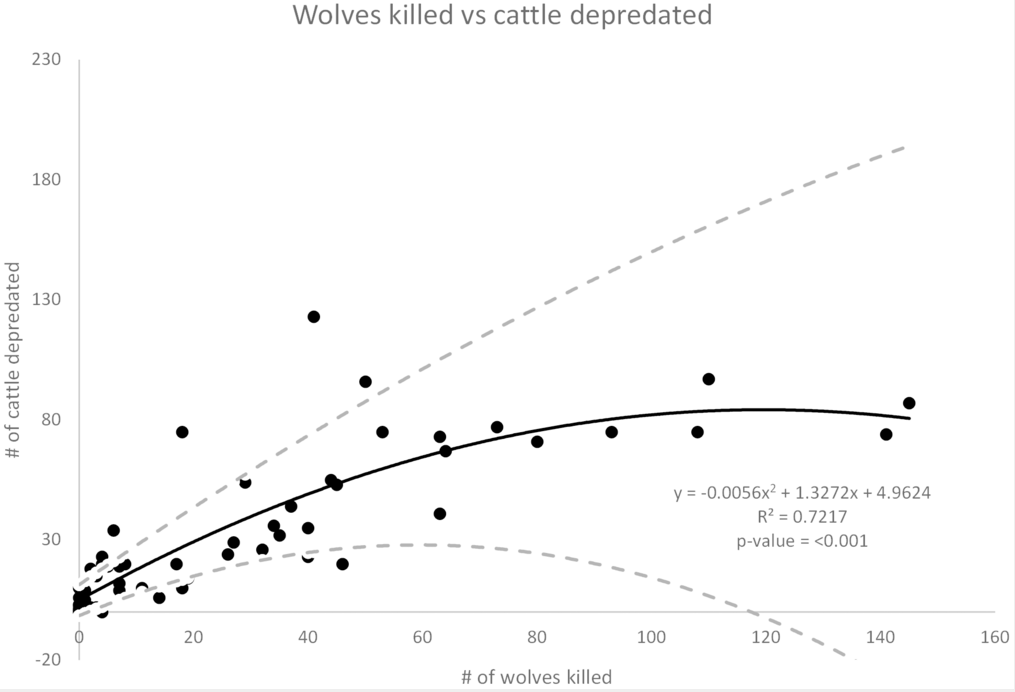

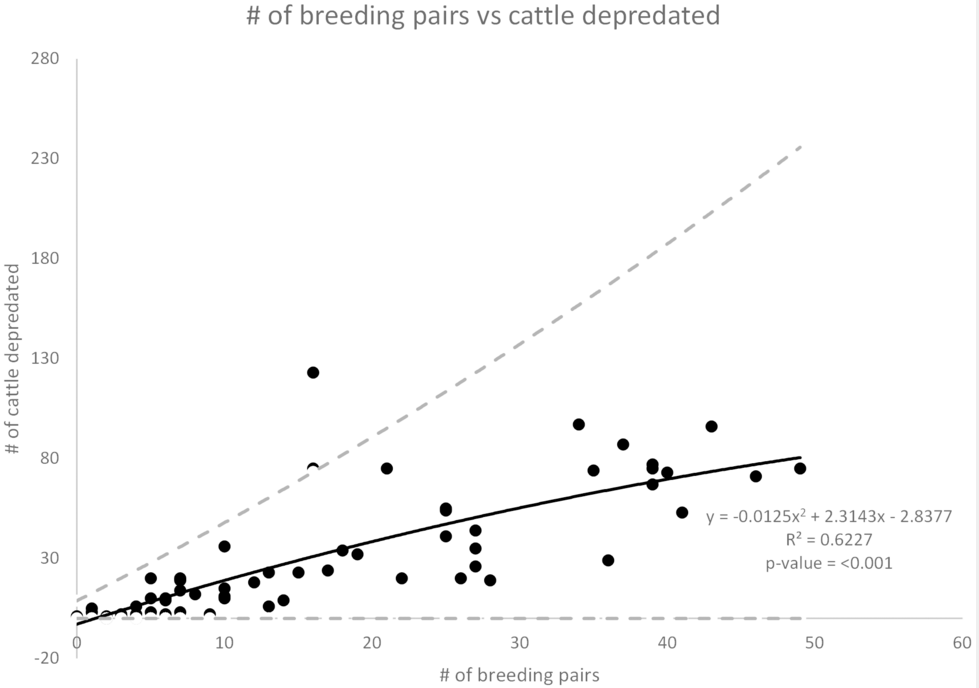

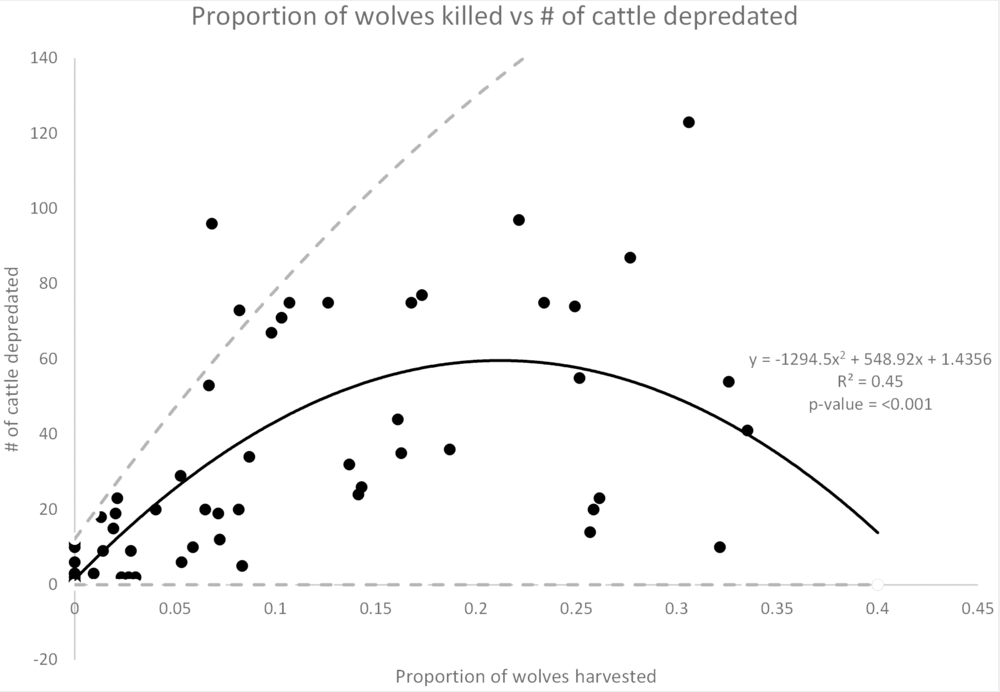

In an incredibly comprehensive and long term study, Wielgus et al. assessed the effects of a wolf cull on reducing livestock depredations in Idaho, Montana and Wyoming from 1987–2012 using a 25 year time series. The number of livestock depredated, livestock populations, wolf population estimates, number of breeding pairs, and wolves killed were calculated for the wolf-occupied area of each state for each year. Unsurprisingly, their results describe a positive association between the number of cattle in a given area, the number of cattle killed, and the number of breeding wolf pairs. In other words, as you increase the number of cows and wolves in a given area, instances of wolf-cow conflict will also rise. Incredibly, however, their data also shows a positive, not negative, association with the number of wolves culled the previous year – meaning culling wolves actually led to more livestock being killed by wolves the following year. “The odds of livestock depredations increased 4% for sheep and 5-6% for cattle with increased wolf control” (graphed in Figure 1.). Wielgus et al., hypothesized that livestock depredation increased when wolves were killed because the cull disrupted pack structures, which in turn, lead to a compensatory increase in breeding pairs, more pups, and more hunting (Figure 2.). This trend was consistent until 25% of the breeding wolf pairs had been culled, after which point livestock predations began to decline from its elevated state (graphed in Figure 3.). As the paper stresses, however, “mortality rates exceeding 25% are unsustainable over the long term.” As you can see in Figure 3., to get to the livestock mortality rate that you started with before the wolf cull elevated depredation levels, you would need to kill over 40% of the breeding wolf pairs. Ultimately, Wielgus et al. concluded that their results do not support the ‘remedial control’ hypothesis of predator mortality which predicts a drop in livestock following increased lethal control. “However,” they write, “lethal control of wolves appears to be related to increased depredation in a larger area the following year.”

Figure 1: Wolves killed versus cattle depredated: The number of wolves culled the previous year plotted against the number of cattle killed by wolves the following year. The black line indicates that as more wolves were killed through control methods, the remaining wolves killed an increased number of cattle. The dashed lines show the upper and lower limits of the 95% confidence interval for the best fit line.

Figure 2: Number of breeding wolf pairs versus cattle depredated: The number of breeding wolf pairs present in a region the previous year plotted against the number of cattle killed by wolves the following year. The black line indicates that as the number of breeding wolf pairs increases, so to does the number of cattle they kill. The dashed lines show the upper and lower limits of the 95% confidence interval for the best fit line.

Figure 3: The proportions of wolves killed versus cattle depredated: The proportion of wolves killed the previous year versus the number of cattle killed by wolves the following year. The black line indicates a 2-way negative interaction. Cattle depredation increased with increasing mortality up until roughly 25% of the wolf population was culled, then the number of cattle killed began to decline.

Echoing their conclusion from a different research angle, Brainerd et al. analyzed pooled data from 148 territorial breeding wolves and found increased movement and dispersal of wolves when the pack’s breeding (alpha) pair was removed. In other words, when you kill the alpha wolf pair who keep the rest of the pack in line, remaining wolves are statistically likely to breed more and spread into new territories. This disruption to the ecosystem is likely to trigger other changes and lead to issues to neighbouring environments.

Similarly, Treves et al. found that the removal of carnivores generally only achieves a temporary reduction in livestock depredation before other predators move in to fill their space and eat their prey. Harper et al. also found that killing a large number of wolves in Minnesota did not reduce the following year’s livestock depredation levels. They did notice, however, that a mere increase in human activity decreased the amount of hunting wolves did in the area.

Caribou Health

Credit: Mark Gocke, Wyoming Game and Fish

Unfortunately, there is yet another layer of concern to add to this complex analysis; caribou health. The University of Alberta’s Center for Conservation Biology began studying this issue after the government of Alberta announced plans to cull up to 80% of wolves in the oil sands in the hopes that it would slow the rate of caribou decline. They conducted dietary analyses had found that 60% of the caribou winter diet consisted of lichen. “This food source is particularly vital to pregnant caribou as it is high in glucose, which is the primary food source to the fetus,” they wrote. If female caribou do not have adequate access to lichen, they explained, it compromises their pregnancies and lowers birth rates.

“They [the government of Alberta] argue that climate change and habitat disturbance are causing deer, the preferred prey of wolves, to move north into the oil sands. Wolves are said to increase in response, increasing the risk of predation on caribou. Our work suggests that there may be better options.”

The conservation biologists suggested that reducing human and industrial activities in lichen rich feeding grounds may be a more effective mitigation strategy than killing wolves.

“Moreover,” they continued, “owing to the preference of wolves for deer, removing wolves from the population to protect caribou could actually place the ecosystem at markedly greater risk by accelerating the expansion of deer into this ecosystem.”

The Columbia Mountains Institute of Applied Ecology has picked up on this theme too. “Caribou decline may be related to too much energy spent on just trying to stay alive,” explained national park warden John Flaa. “Over the past summer, the three caribou mortalities I investigated had no body fat, which is bound to have an effect on calf production. Census results here show that the proportion of calves in the herd are below replacement level.”

Accessing an adequate food supply has been an ongoing issue for elk too, especially across the border in Wyoming. Their Game and Fish Wildlife Division, however, has managed to greatly inflate herd size over the last few decades by feeding them hay every winter. Not surprisingly, issues of disease began to increase as more elk congregated at feeding grounds. As Creech et al. explained; “High seroprevalance for Brucella abortus among elk on Wyoming feedgrounds suggests that supplemental feeding may influence parasite transmission and disease dynamics by altering the rate at which elk contact infectious materials in their environment.” Thankfully, they have also since shown that spreading out feeding areas reduces cross contamination infection rates by 70%.

This is not an ideal solution, of course, but it has been quite successful in many respects. Elk populations in Wyoming are now strong enough to support hunting, an activity that more than covers the cost of the feeding program. “Elk hunters spent $49.9 million in 2012… The program cost $558 per animal and generated $1,856 in ‘economic return’ per [elk].”

Conclusion

As Dr. Adam Ford wrote in his summary paper Science, Uncertainty, and Ethics in the Alberta Wolf Cull; “It is past time that we adopt a more creative view of how we can coexist with caribou and wolves in an industrialized landscape.” After reviewing the literature available on this and related issues I agree. While this is an undeniably complex situation with a lot at stake, I think we should be doing more to learn from innovative wildlife managers around the world.

We could try creating a geo-fence between wolves and threatened caribou like conservation officers do with their problem elephants in Kenya. Or get ‘caribou shepherds’ to track GPS collared herds, intervening when they are at risk of predation; much like the ‘marmot shepherds’ who saved endangered (admittedly easier to track) colonies on Vancouver Island. We could explore the feasibility of capturing, sterilizing, and re-releasing the alpha breeding pair in a pack of wolves; thereby reducing the growth of a wolf population while keeping the governing pack structure in place. Given the above concerns about food availability for caribou, as well as the effective use of feed lots elsewhere, I think we should also consider supplementing the diets of the South Selkirk and Peace region herds with a stable supply of lichen over the winter. It would be a relatively cost effective, simple, and could potentially be game-changing for our struggling caribou.

Some of these solutions may sound crazy, but when you consider we are currently spending millions of dollars to indiscriminately shoot wolves from helicopters, I would argue they potentially offer for more cheaper and less-crazy alternatives.

Acknowlegements

We are sincerely grateful to the many scientists who made time to talk to us about their work.