The Pacific Coast Herring Fishery

The long-standing Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) policy to allow a Sac-Roe Fishery (SRF) harvest of herring eggs has always been incredibly wasteful and shortsighted. It is an industry that has triggered a cascading decline of economic, cultural and ecological well-being in B.C. The intensive reduction fishery started in the early 1930s and continued until all five major stocks collapsed in the late 1960s. Pacific herring populations recovered rapidly following a four year fishery closure but the species is prone to collapse and abundance has declined again recently, with little evidence of recovery. Using seine or purse nets to capture schools of pre-spawn herring, SRF boats can kill thousands of tonnes of fish in a matter of minutes. Of those huge catches, only the roe is removed for human consumption; the carcasses are treated as by-product and used to make feed tablets for fish farms, bait or put into garden fertilizers. As herring can spawn seven or eight times over their lifetime, this kill-fishery not only removes huge biomass from the overall herring population, but destroys their ability to reproduce in future years.

Herring captured in seine nets March 2015, photo by Ian McAllister

Herring captured in seine nets March 2015, photo by Ian McAllister

This fishery is systematically extirpating one of B.C.’s most important foundational and keystone species. Granted, there are many other wasteful industries in our country, but what makes this one so spectacularly so is the fact that there is a clear, effective, and sustainable alternative. It is not a new method of harvesting herring eggs, quite the opposite, it has been used along the B.C. coast for thousands of years. Herring bones that have been uncovered deep in the substrate of ancient village sites provides evidence of the long relationship between the first peoples of this coast and herring.

The Heiltsuk people today, like the countless generations before them, travel to the traditional herring spawning grounds in anticipation of the inshore herring migration. Heiltsuk families anchor logs and other flotation devices to the seabed and attach lines of hemlock branches or seaweed to them – essentially mimicking ideal herring spawn habitat. With luck, herring will see these branches and kelp fronds and choose them as a spawning location, after a few days multiple layers of eggs will coat the vegetation and the harvest can begin.

Spawn-on-kelp herring roe harvest. Kelp covered in eggs are pulled from the water on the central B.C. coast, photo by Ian McAllister

Spawn-on-kelp herring roe harvest. Kelp covered in eggs are pulled from the water on the central B.C. coast, photo by Ian McAllister

The Heiltsuk choose hemlock branches because of the needles’ flavour and medicinal benefits, but also because the natural resins provide a lot of sticky surface area for the eggs to attach themselves. Certain species of kelp are preferred over hemlock by some families, and spawn on kelp remains the main product used for export.

Hemlock branches coated with herring eggs, harvested near Bella Bella, B.C. Photo by Max Bakken

Hemlock branches coated with herring eggs, harvested near Bella Bella, B.C. Photo by Max Bakken

These days, as the world’s oceans are picked clean for human consumption, the words ‘sustainable fishery’ have lost their meaning. In contrast, this traditional fishery has a very small footprint. It also maximizes ecological and economic benefits as the herring get to live and continue to spawn for successive generations.

Compare this to the DFO industrial-scale kill fishery model and it becomes shameful that the Heiltsuk and other Nations have not been more supported for the long battle that they have been waging against DFO, both in the courts and by active blockades on the herring grounds – to shut this unsustainable fishery down. Like the east-coast cod and so many other fisheries that have collapsed at the hands of DFO, herring stocks here are following the same path and hundreds of traditional spawning areas in the territory have gone silent.

Seine nets set to harvest herring on the B.C. central coast, photo by Ian McAllister

Seine nets set to harvest herring on the B.C. central coast, photo by Ian McAllister

When the Heiltsuk fishers go out on the grounds they are bringing with them generations of experience and knowledge. The logic behind the SRF industry, however, hits a dead-end pretty quickly. One does not have to use much foresight to see that a fishery founded on the mass and unnecessary killing of future spawning populations is doomed to harvest itself into the ground. All of the hallmarks of hunter-overkill are evident with the herring fishery. More corporate control of the fishery, more technology being used with bigger boats and hi-tech sonars while the fish get smaller in size forcing more immature fish to be harvested. This not only destroys the fish with greatest lifetime spawning potential, it is not even profitable as immature fish (2-3 years old) have fragile stomach linings that burst before any roe can be harvested.

The DFO releases an annual ‘Pacific Herring Integrated Fisheries Management Plan’, which, on the surface, appears to be a comprehensive report. Reading ten years worth of these documents, however, only further convinced me that the DFO not only has a limited understanding of herring’s ecological importance, requirements, or how to safely manage them, they also don’t seem to care. Take this section of the 2004 report, for example: “At this time there is no information available on the appropriate conservation limits for the ecosystem as it pertains to the herring stocks”. It continues on to talk about harvest rates, and ends with: “Research is ongoing to better understand these ecosystem processes and the role herring plays in maintaining the integrity and functioning of the ecosystem.” This paragraph, on page two, appears sincere enough, a commitment to future herring research is definitely important. I then read the exact, word for word, statement in the 2013 report. Nine years later they have failed to do any of the conservation research they claimed to be working on, and they don’t even care enough to write a new excuse.

In 1996 conflicts between First Nations’ fishing practices and DFO’s regulations reached the Supreme Court of Canada when two Heiltsuk brothers, William and Donald Gladstone, were arrested for selling SOK. In what has become known as the Gladstone Commission, the Heiltsuk Nation argued their case and became the first Nation in Canada to be granted a court-affirmed, un-extinguished aboriginal right to commercially harvest and sell SOK. Unfortunately, this victory was not the end of the Heiltsuk Nation’s struggle with DFO. The SRF continued to kill thousands of tonnes of herring biomass every year resulting in extirpation of stocks throughout the territory.

In March, the Heiltsuk declared a tribal ban on commercial sac roe fishing in all of Area 7, including Spiller Channel, to preserve the region’s threatened herring stock. DFO opened the herring sac roe seine fishery in Spiller Channel shortly after.

“This action shows blatant disrespect of aboriginal rights by DFO and industry,” Chief Councillor Marilyn Slett told the CBC.

“DFO provided inconsistent and misleading communications throughout the day and did not attempt meaningful consultation,” said Slett.

“We must put conservation first. We have voluntarily suspended our community-owned commercial gillnet herring licenses for this season to allow stocks to rebuild, but DFO and industry are unwilling to follow suit,” said Kelly Brown, director of the Heiltsuk Integrated Resource Management Department.

In response to the situation, Fisheries and Oceans Canada told the CBC “We were committed to providing harvest opportunities where they were possible. A purse seine fishery did occur on March 22nd, yielding 690 tons of an available 800 tons. This fishery is now closed.”

The historical and ongoing treatment of herring by DFO is a tragedy. The constant theme underlying years of collapses and management failures is a complete disregard for the essential role these forage fish play in B.C.’s ecosystem and First Nations culture. Whales, dolphins, seals, sea lions, cod, salmon and sea birds all feed heavily on herring, making those small fish hugely important in the coastal ecosystem. This miraculous, mysterious species – which provides a foundation for so many – needs more support.

Banner Image: Shoreline waters change colour as the herring spawn begins in the Great Bear Rainforest, photo by Ian McAllister

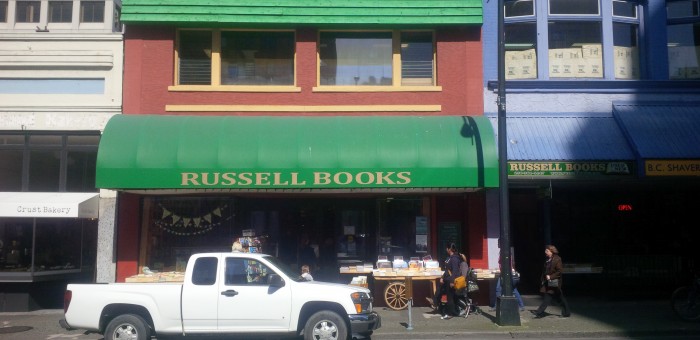

Celebrating Local Businesses in Our Community – Russell Books

Building on the success of our Celebrating Youth in Our Community series, we’ve decided to initiate a series highlighting innovation and creativity within our region’s small business sector. This is the first of our series where we celebrate an innovative partnership between Russell Books and local schools.

Meeting at the sunny entrance of Russell Books, I joined the store’s manager, Andrea Minter, and very passionate group of teachers and parents to discuss their vision for inspired book fairs in Victoria schools – fairs that move beyond the corporate Scholastic model to integrate student’s interests with a small local business and sense of community. Sarah McLeod (a constituent of OBGH), the teacher-librarian at St. Margaret’s School currently doing her Master’s on the transformation of libraries to learning commons, Jennifer van Hardenberg, the communications coordinator for St. Margaret’s School, two of their Parents’ Auxiliary members, Victoria Davis and Stephanie Neilson (a constituent of OBGH), and I sat amongst great literary company in the vintage books section while they told me about the budding partnership between Russell Books and local schools.

Russell Books was started by Andrea’s grandfather, Reg Russell. He was a banker, she explained, with a book collection that outgrew his home. Andrea’s grandmother suggested he take all his books and open a small store and, in 1961, Mr. Russell did just that, starting with a 300 square foot book shop in Montreal. The store packed up and moved to Victoria in 1991 where it was run by Andrea’s parents. It has continued to expanded from its humble beginnings and now consists of 16,000 square feet of new and used books, all managed by Andrea and her husband.

Fed up with plastic book fairs that seemed designed to push stuff on their kids instead of celebrating the joy of reading, Sarah and Andrea joined forces to host their first-ever non-scholastic book fair at St. Margaret’s elementary school, building off similar fairs Andrea had hosted at Sir James Douglas where her children were students. On all levels, they said, it was a huge success. “We wanted to start slow,” Andrea said, “to make sure we were doing it right.”

“There is waste [associated with Scholastic fairs] and the books are also quite expensive,” added Sarah describing the metal boxes that would follow the shiny pamphlets to her library, chock-full of individually wrapped erasers and posters. “Russell Books provides a variety of prices [$2-20], a sense of community and warmth. It’s just a different feeling.”

70% of the books at Russell Books are used and readers can swap them back for store credit at the store once they are done, an element that provides students with a valuable lesson in sustainability and sharing.

The team working to grow and expand Russell book fairs to more schools is keen to keep kids involved. Over the past few years, the weeks leading up to their fairs are spent exchanging countless emails and phone calls about special books students are hoping will be at the fair.

“It’s all about forming connections and relationships – connecting the virtual and physical worlds found in stories, connecting schools with their community, connecting kids with books,” said Sarah.

Students have been engaged and excited about the fairs, and so have the staff at Russell Books. Before we wrapped up our meeting I asked Andrea what their capacity for expansion would be if other schools came forward interested in collaborating for their own fair, “absolutely,” she said, “we have an amazing staff here and everyone is keen to work at the book fair.” Not to mention they have over a million titles to choose from. The next fair at St. Margaret’s will be at the end of this month, coinciding with grandparent’s day.

It’s exciting to envision the potential whereby local booksellers partner with local schools to host book fairs that cater to the specific interests of our school communities. Thank you Russell Books for being an innovator in this regard.

Private Member’s Bill Tabled to End Trophy Hunting in B.C.

On Monday, March 2nd, I tabled a bill that restricts the practices of non-resident trophy hunters coming to B.C. to kill large game by making two specific amendments to the Wildlife Act.

The proposed changes remove grizzly bears from the list of animals exempt from meat harvesting regulations and ensure all edible portions of game animals killed in B.C. are taken directly to the hunter’s residence.

As the legislation currently stands, it is illegal to waste meat when hunting in B.C., unless the animal you have killed is a cougar, wolf, lynx, bobcat, wolverine, or grizzly bear. The edible parts of big game animals must be removed from the animal and packed out to one’s home, or importantly for non-resident hunters, to a meat cutter or a cold storage plant. These last two options provide trophy hunters with legal meat laundering opportunities. By adding “directly or through” to the clause hunters can still use meat cutters and cold storage plants to process their harvests, but it can’t end there. The meat must make it to their home address. If they want to donate that meat to charity after the fact they are welcome to do so, but they have to take it home first.

Hunters are already required to remove the edible portions from black bears, if enacted, this bill would bring meat harvesting standards for grizzly bears up to the same level.

For local sustenance hunters – the vast majority of hunters in B.C. – this bill merely echoes what they are already doing; harvesting wild game to bring the meat home to feed themselves and their families. For non-resident trophy hunters coming to B.C. to bag an animal for its hide, skull, or antlers this poses a larger logistical challenge of exporting large quantities of meat.

The purpose of this Bill is to provide the government with another tool to address the growing concerns about trophy hunting in our province. As with any tool the government develops, its effectiveness is entirely dependent on government’s commitment to using it as it was designed. If government were to pass this bill, but fail to enforce its provisions, or provide regulatory loopholes for guide outfitters, then its purpose will be undermined. It will be up to government to make a commitment to embracing the values that are at the heart of this Bill and using them in a meaningful manner.

This is not a perfect solution, of course, but it is an achievable step in the right direction of protecting the interests of sustenance hunters while reducing the wasteful influence of non-resident hunters who come to our province to kill our wildlife acting with disregard for its value as a food source. It is also a strong legislative move towards conserving grizzly bear populations in B.C. as it forces the government to reevaluate its outdated grizzly hunting mandate. It shows the current government that we are serious about conserving grizzly bears through working collaboratively with conservation organizations like the British Columbia Wildlife Federation, BC’s First Nations and BC’s resident hunters.

Brown bears, of which grizzlies are the North American subspecies, were once found on four continents, making them one of the most widespread mammal populations in the world. Their original range included Europe, North Africa, northern and central Asia, the Middle East, and North America. Today, they are locally extinct or endangered across the map — except in Russia, Alaska, and B.C.

According to the provincial government’s 2002 report on B.C. grizzly bears, in North America healthy grizzly bear populations once extended from northern Mexico to the Yukon, and from the West Coast to Hudson Bay. As human populations began to expand, grizzly numbers steadily declined as their habitat became fragmented, their food sources threatened, and they were killed for recreation and for getting too close to the people who were moving into their territory.

British Columbia and Alaska are the last strongholds of grizzly bear populations on the planet, though the exact numbers are contested because the bear’s solitary and roaming nature makes them difficult and expensive to study. The B.C. government estimates there are 15,000 grizzly bears in the province today, some independent scientists and First Nations groups think there could be as few as 6,000.

Precise population number aside, the global trend for brown bears is clearly one that favours extinction. The Himalayan brown bear has dwindled to two per cent of its former range and there are an estimated 49 brown bears left in Italy. Mexico’s grizzlies are now extinct and the last known Californian grizzly was shot in the 1920s. The Liberal government maintains the fate of B.C.’s grizzly bears will be different, but the government’s scientific justifications for the hunt in some regions are harshly criticized by many local and international scientists.

Like Canada’s polar bears, B.C.’s grizzly bears have been listed as a “species of special concern” by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). Unlike their Arctic cousins, though, grizzly bears don’t qualify for federally legislated conservation measures.

In addition to the unrelenting pressure brought by climate change, industrial expansion, and habitat destruction, this iconic species is pursued by “hunters” who come to B.C. to kill a prize bear. The importation of B.C. grizzly bear parts into the European Union has been banned for over a decade because they think the hunt is being unsustainably managed. The wealthy non-resident hunters who come to our province to buy a grizzly trophy, therefore, are predominantly from the U.S. They cut off the bear’s head, paws, and fur but leave the bodies behind to rot.

This so-called sport has been banned by nine coastal First Nations and is opposed by nearly 90 percent of British Columbians. Importantly, 95 percent of hunters surveyed in the province-wide McAllister Research poll also agreed that people should not be hunting if they are not prepared to eat what they kill.

I support sustainable, respectful sustenance hunting in British Columbia that is grounded in a science-based conservation policy. It with this in mind that I introduced the Bill today.

This bill is an attempt to bring the environmental and hunting communities together. Many urban environmentalists don’t realize that BC hunters and their supporting organizations (like BCWF, Ducks Unlimited and Fish and Wildlife organizations) are some of the most active conservationalists. At the same time, some hunters believe that most urban environmentalists are out to stop hunting. The reality is that almost everyone I have spoken with is on the same page. They support hunting for food. They don’t support hunting only for trophies. This bill supports the former and penalizes the later.