Let’s explore the concept of basic income: Please let me know what you think

Over the next few weeks I will explore the concept of “Basic Income”. I would be most grateful if you would share your comments, suggestions and concerns with me about this topic as we unpack what it all means in a series of upcoming posts. In this first post we simply provide a backgrounder.

1. What is “Basic Income”?

A basic income is a regular payment that the Government makes to individuals or families in its jurisdiction, which is not contingent on recipients fulfilling specific criteria (e.g. proving that they are active job seekers).

Basic income comes in two basic forms: means-tested and universal. In its means-tested form, a basic income is paid only to those whose income from other sources falls below a predetermined threshold, but is not contingent on recipients’ willingness to work. It is often referred to as “guaranteed minimum income”. In its universal form, a basic income is paid to all, irrespective of income from other sources. The unconditional basic income is often referred to as “universal basic income” or a “citizen’s’ wage”.

The idea of a basic income has become more popular recently, and has garnered support from across the political spectrum. In Canada, Ontario is planning a pilot next year, and Quebec, Alberta, and PEI have also raised the possibility of running pilots in the near future. Internationally, Finland and the Netherlands are both staging large-scale pilots in 2017.

2. Background

a. Poverty and Inequality in BC

The levels of poverty and inequality in BC are high relative to the national average. BC has higher than average rates of poverty, with poverty rates up to 16% and child poverty rates up to 20%, depending on the poverty measure used. BC also has one of the highest levels of inequality in Canada, estimated to be second only to Alberta.

For those needing support, our current system of social programs has a number of shortcomings. The siloed approach, with a myriad of different programs with specific eligibility criteria, allows people to slip through the cracks in the system and leaves many unsure which benefits they are eligible for. It also has a substantial administrative cost. There is significant stigma in collecting welfare today, and many argue that the invasiveness of the current approach, with its stringent conditionality and reporting requirements, strips recipients of privacy and dignity. Additionally, the current system may provide a disincentive for many to join the workforce, due to how quickly the benefits are reduced as any income is earned.

b. A Shifting Economy

Unprecedented technological advance, of rapidly increasing pace, is set to have a significantly disruptive effect on our economy. To now, we have seen deindustrialization and the closure of industries, together with a boom and bust economy in British Columbia that almost defines much of provincial economic history. With increasing automation, forecasts suggest the potential for the rapid elimination of jobs across a wide range of sectors. Automated voice recognition software is already replacing many call centre workers, car assembly plants use more robots than people, and driverless cars and trucks are already significantly impacting the taxi and trucking industries. The effects of automation are predicted to be most strongly felt in moderate and low-paying jobs: Barack Obama’s 2016 economic report predicted that jobs paying less than USD$20/hour face an 83% likelihood of being automated, while jobs paying between $20 and $40/hour face a 33% chance. In the UK, one third of retail jobs are forecasted to be replaced by 2025. The effects of automation are predicted to spread to higher paying professional sectors as well, particularly the medical and legal professions. Technological advance has been attributed as a cause of increasing inequality by a number of economists because of automation’s effects on jobs and technology’s role in further concentrating the accumulation of wealth in the hands of top earners.

We are also heading toward what is commonly termed the ‘gig’ economy. We are shifting away from the 20th century model of permanent full-time work with benefits toward precarious contract-based work, which is spreading at an increasing rate to workers at all levels of education, trade, skill and profession. Contract-based employment means employers, with an expanding labour pool, can negotiate pay, usually with few or no benefits, outside of union negotiated packages. Examples today include Uber drivers, health care assistants, and sessional lecturers at postsecondary institutions.

3. Potential Effects of a Basic Income: Opportunities and Challenges

Perhaps the most transformational promise of a basic income is its potential to raise recipients out of poverty. Living in poverty takes a significant toll, and the elevated levels of stress that it brings are associated with higher levels of alcohol and drug abuse, domestic abuse, and mental health problems. Those living in poverty are more likely to have inadequate nutrition, use tobacco, be overweight or obese, and be physically inactive. The adverse effects of growing up in poverty on a child’s ability to be successful in school and integrate into the workforce contribute to generational poverty.

The moral case for tackling poverty is self-evident: doing so would have a life-changing effect on the lives of those currently living in poverty and dealing with the problems it brings on a daily basis. The financial cost is also significant: the adverse outcomes of poverty lead to increased use of public health care, more hospitalizations, and lost economic activity, among other effects.

A pilot project undertaken in Manitoba in the 1970s suggests that a basic income policy can have significant impacts on the healthcare system: providing a basic income to residents of Dauphin, Manitoba for 3 years reduced hospital visits by 8.5%. The decrease in hospital visits was attributed to lower levels of stress in low income families, which resulted in lower rates of alcohol and drug use, lower levels of domestic abuse, fewer car accidents, and lower levels of hospitalization for mental health issues.

A basic income could also provide a means to respond proactively to the changes we are just beginning to see in the labour market. As the effects of automation are realized, providing a basic income would enable those affected to retrain for new professions, attend or return to University or College, take entrepreneurial risks, contribute to their communities or other causes through volunteering and civic engagement, and invest time in their families.

A challenge in considering a basic income scheme is predicting its effects on the labour market, specifically the extent to which it might provide a disincentive to work comparable to or stronger than the disincentive often associated with our current social assistance programs. The Dauphin, Manitoba pilot study provides some initial information on this question: it was found that the negative effect on people’s willingness to work was minimal for the general population, but more pronounced for mothers with young children, and teenagers aged 16-18 who completed high school instead of leaving to join the workforce.

A recent report by the Vancouver Foundation advocates paying all youth ages 18-24 transitioning out of foster care a “basic support fund” of between $15,000-$20,000. Doing so, they estimate, would cost $57 million per year, whereas the cost of the status quo is between $222-$268 million per year, due to the range of adverse outcomes that affect youth in transition, including intergenerational poverty, criminal activity, substance abuse, lost educational opportunities, and homelessness. Thus they estimate that establishing a basic support fund for youth in transition would result in savings to the Provincial Government of $165-$201 million per year.

The cost of a basic income program is difficult to predict, and estimates range widely according to assumptions made about the characteristics of the program and its social and economic effects. In costing a basic income it is important not to ignore the cost of the status quo: the direct costs of unemployment, poverty, and homelessness as well as the costs of managing the adverse effects. Nonetheless, the cost of a basic income program to BC is potentially significant, and costs associated with different implementation options must be fully worked out and tested.

4. So what are your thoughts?

While I recognize that I’ve only provided cursory information to initiate this conversation, I would like to hear your thoughts on the idea of a basic income. Do you think a basic income policy holds promise as a potential way forward in BC, allowing us to tackle poverty effectively and prepare for a future in which the nature of work is vastly different from what we have known in the past? What are your concerns about the policy? How would you like to see it implemented? Thank you in advance for your comments.

GMOs: An Update and Potential Ways Forward in BC

Introduction

Since writing our first backgrounder, we have continued to research the issues surrounding genetically modified foods, and the legislative options available in the BC context. The issue of GMOs is broad and complex and is tied to many larger questions including: our relationship to our food, the effects of large-scale conventional agriculture on human and animal health and the environment, population growth, global warming, industry funding of science, technological advance and its associated risks, and our ability to ensure a sustainable and secure food supply for the future. It is important to be cognizant of these broader issues in developing a response to GMOs, to ensure a well informed and holistic response that does not have unforeseen adverse consequences. We must also work within the context of BC, using the tools we have at our disposal to most appropriately and effectively respond to the issues and questions associated with GMOs.

Jurisdiction

Health Canada and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) share responsibility for food policies on health and safety, regulation, and labelling. The BC Liberal government has said that the responsibility for GM products rests solely with the Federal Government (see here and here and here).

However, in 2001, the BC NDP argued that GM labelling is a consumer information matter, which falls under provincial jurisdiction according to the Constitution Act (1867). During second reading of Bill 18 Genetically-Engineered Food Labelling Act, NDP Attorney General Graeme Bowbrick noted “The province has jurisdiction to legislate on a matter of property and civil rights, which is interpreted to include the authority to legislate with regard to consumer protection and consumer information.”

The Food and Agricultural Products Classification Act (2016) gives the Lieutenant Governor in Council the power to make regulations establishing or adopting certification programs, including making regulations respecting the quality standards of food or agricultural products. However, provincial certification will only apply to operators producing and selling their products within BC; those that sell their produce to other provinces will still require federal certification.

In order to fall within BC’s jurisdiction, the impact of any legislation must only be felt within BC and it must not have the effect of prohibiting or controlling the importation of goods into the province. Otherwise, legislation would infringe upon federal jurisdiction over inter-province trade and commerce and therefore be invalid.

Regarding pesticides, a province may prohibit the use of a registered pesticide, or it may add more restrictive conditions on the use of a product than those established under the Pest Control Products Act. This may provide a relevant parallel for the Province’s ability to restrict GM crops that have been approved Federally, or to impose stricter regulations on the use of GM crops within the province.

Effects and Costs of Mandatory Labelling

The BC NDP estimated that mandatory labelling would cost $11.8 million (in today’s dollars; see Note 1 below), which equals 0.1% of total retail food sales in BC. If implemented, mandatory labelling in BC could result in nation-wide labelling by companies, as is happening in the US, where Vermont labelling legislation (going into effect on July 1st, 2016) has led to large companies – including General Mills, Mars and Kellogg – to label their products nationwide.

Potential Ways Forward in the BC Context

Many potential legislative responses to GMOs fall under federal jurisdiction, including the approval and regulation of GM crops for growth and sale in Canada.

In BC, two key responses may be warranted. First, the Ministry of Agriculture could establish a robust tracking and monitoring regime, to track where GM crops are grown in BC, and to pro-actively monitor any actual or potential environmental and agricultural effects of GM crops. The Province does not currently track or monitor GM crops in BC. If any action is warranted, we must first identify and fully understand the scope and impact, if any, of GM crops in our province.

Second, BC should establish an expert panel, made up of independent researchers, to assess the current and potential future impacts of GM agriculture in BC, and to assess the jurisdictional ability, logistics, and costs of implementing mandatory labelling in BC or of increasing the regulation or restriction of GM imports into BC. Independence is important since many studies on GMOs are industry funded, but not all. Some evidence suggests that industry funding systematically biases studies towards favourable outcomes (see Note 2)

So what do you think?

Please continue to share your thoughts on what we should do in BC to address potential or perceived concerns associated with certain GM crops.

Note 1: adjusted 2001 NDP estimate ($9 million) for inflation (BC Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General, Regulatory Impact Statement, April, 2001)

Note 2: Healthy People and Communities—Steering Committee, Multi-Sectoral Partnerships Task Group, 2013: Discussion Paper: Public-Private Partnerships with the Food Industry;

Ayevard, P., D. Yach, A.B.Gilmore, and S. Capewell, 2016: Should we welcome food industry funding of public health research? The BMJ, 2016, 353:i2161. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2161.

Labelling of GMOs: A backgrounder & what do you think?

Introduction

Genetically modified (GM) foods are widespread in Canada, with the potential for further expansion. Though the majority of studies show no negative health effects from consuming GM foods, there is controversy regarding the validity of these studies, and many significant concerns and unanswered questions regarding their effects on the environment.

Background

Genetic Modification (GM) refers to the introduction of new traits to an organism in a way that does not occur naturally, by making changes to its genetic makeup through intervention at the molecular level.

Genetic Modification (GM) refers to the introduction of new traits to an organism in a way that does not occur naturally, by making changes to its genetic makeup through intervention at the molecular level.

The first GM crops were approved for sale in Canada in the mid 1990s, and they have since become pervasive: they are found in more than 70% of processed foods sold in North America. More than 90% of canola and sugar beets, 80% of corn and 60% of soy grown in Canada are genetically engineered.

While genetic modification can be undertaken for a variety of purposes, including nutrition improvement, virus resistance, and drought resistance, virtually all GM crops on the market today are engineered exclusively for herbicide tolerance or insect resistance.

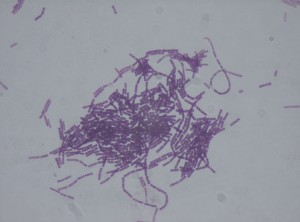

Herbicide tolerant crops have been engineered to withstand application of herbicides: most common is Monsanto’s “Roundup Ready” corn, which tolerates glyphosate. Crops engineered for insect resistance produce their own pesticides. The most common are Bt crops, such as Bt Cotton and Bt Corn, which are engineered to synthesize Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) endotoxin in their cells, making them toxic to some insects. Many GM crops are “stacked” with both herbicide tolerance and insect resistance.

Herbicide tolerant crops have been engineered to withstand application of herbicides: most common is Monsanto’s “Roundup Ready” corn, which tolerates glyphosate. Crops engineered for insect resistance produce their own pesticides. The most common are Bt crops, such as Bt Cotton and Bt Corn, which are engineered to synthesize Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) endotoxin in their cells, making them toxic to some insects. Many GM crops are “stacked” with both herbicide tolerance and insect resistance.

There is a strong “right to know” movement advocating mandatory labelling of GM foods in the US and Canada. Polls show that 90% of Canadians support mandatory labeling, and 64 countries around the world have mandatory labelling. Going further, some countries have banned the cultivation of GMOs altogether. Some US states have passed mandatory labelling laws, but a bill is currently under consideration in the US Senate, which would mandate that any such labelling takes place only at the Federal level, and only if health and safety is shown to be at issue.

There is a strong “right to know” movement advocating mandatory labelling of GM foods in the US and Canada. Polls show that 90% of Canadians support mandatory labeling, and 64 countries around the world have mandatory labelling. Going further, some countries have banned the cultivation of GMOs altogether. Some US states have passed mandatory labelling laws, but a bill is currently under consideration in the US Senate, which would mandate that any such labelling takes place only at the Federal level, and only if health and safety is shown to be at issue.

Some of the Key Issues

GMO foods have been widely consumed for 20 years. The majority of scientific studies undertaken suggest no negative health effects from consuming GMOs (see here and here). However, there are a number of criticisms aimed at these studies, including their short-term nature and the fact that industry funds a large proportion of them.

Some studies have shown negative health effects of GM foods, including toxicity, immune responses, hormonal effects, and allergenicity, but their results are also contentious within the scientific community. Many of the studies showing negative health effects focus on the effects of glyphosate, which the World Health Organization has listed as a probable human carcinogen, and Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt), which are present in GM crops but are also used in conventional, and, in the case of Bt, organic agriculture. It is debated whether the levels at which Bt is found in GM crops are higher or lower than in conventional or organic crops, and whether there are qualitative differences in Bt, with human health and environmental implications, depending on how it is used.

Some studies have shown negative health effects of GM foods, including toxicity, immune responses, hormonal effects, and allergenicity, but their results are also contentious within the scientific community. Many of the studies showing negative health effects focus on the effects of glyphosate, which the World Health Organization has listed as a probable human carcinogen, and Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt), which are present in GM crops but are also used in conventional, and, in the case of Bt, organic agriculture. It is debated whether the levels at which Bt is found in GM crops are higher or lower than in conventional or organic crops, and whether there are qualitative differences in Bt, with human health and environmental implications, depending on how it is used.

The environmental effects of GM crops are a second key issue. Herbicide resistant plants – so-called “super weeds” – are on the rise, resulting from the widespread use of herbicides, particularly glyphosate. Herbicide use has increased significantly since the advent of GM crops; one study estimates a 15-fold increase between 1996, when glyphosate-resistant crops were introduced, to 2014. Many draw a direct link between herbicide-resistant GM crops and the increase in herbicide use (see here and here, for example). In response to weed resistance to glyphosate, chemical companies are developing new herbicides and engineering crops to resist them, such as 2,4-D resistant corn and soybeans, grown with Dow’s Enlist Duo, which combines herbicides 2,4-D and Glyphosate.

The other major GM crop, modified with Bt to resist insects, has led to a reduction in the use of chemical insecticides in the US (the Canadian government does not track the impact of Bt crops on insecticide use). However, it is debated whether the GM plants have more or less pesticides present than those used in conventional or organic agriculture. Furthermore, since Bt has been used so widely in GM crops, insects are becoming resistant to it, thus farmers may have to switch to other, more toxic pesticides (see here, here and here).

The other major GM crop, modified with Bt to resist insects, has led to a reduction in the use of chemical insecticides in the US (the Canadian government does not track the impact of Bt crops on insecticide use). However, it is debated whether the GM plants have more or less pesticides present than those used in conventional or organic agriculture. Furthermore, since Bt has been used so widely in GM crops, insects are becoming resistant to it, thus farmers may have to switch to other, more toxic pesticides (see here, here and here).

In terms of contamination, GM crops have the ability to contaminate organic farms, which prohibit the use of genetic modification, thereby making organic farming difficult or impossible in regions close to GM agriculture. There is a largely unknown risk of transgene transference from GM crops to wild gene pools: some instances of transference have been reported, but the extent and future potential is unknown.

A Canadian expert panel put together by the Royal Society of Canada noted that the uncertain environmental impacts of GM crops could justify mandatory labeling. Independent research is lacking, as research is primarily funded by industry. The Canadian government doesn’t undertake an independent review process of industry studies on the health and environmental safety of their products before approving them.

Underlying discussions of the health and environmental effects of GM crops is a problem with treating GMOs categorically. Genetic modification is a process that can be used for different purposes and to a wide variety of effects. As noted, while herbicide resistant GM crops are associated with increased herbicide use, pesticide producing GM crops, such as Bt crops, have reduced the use of chemical insecticides. Genetic modification can potentially improve nutrition, such as “Golden Rice” with vitamin A added, or GM potatoes that release fewer carcinogenic acrylamides when cooked; it can make crops virus resistant, by inserting virus proteins into the DNA, as with the GM papaya; and it can help plants become drought resistant, potentially improving global food security. A key point of criticism of mandatory labelling is that it does not differentiate between the types of modification taking place, and their associated effects on human health or the environment.

Underlying discussions of the health and environmental effects of GM crops is a problem with treating GMOs categorically. Genetic modification is a process that can be used for different purposes and to a wide variety of effects. As noted, while herbicide resistant GM crops are associated with increased herbicide use, pesticide producing GM crops, such as Bt crops, have reduced the use of chemical insecticides. Genetic modification can potentially improve nutrition, such as “Golden Rice” with vitamin A added, or GM potatoes that release fewer carcinogenic acrylamides when cooked; it can make crops virus resistant, by inserting virus proteins into the DNA, as with the GM papaya; and it can help plants become drought resistant, potentially improving global food security. A key point of criticism of mandatory labelling is that it does not differentiate between the types of modification taking place, and their associated effects on human health or the environment.

Mandatory labelling has a significant amount of public and political support, advertised as a means to give customers the ability to know what they are eating. The effect of mandatory labelling on consumer demand is debated: some argue that it will be widely perceived as a warning, thereby decreasing consumer demand for GM products. In response to consumer demand it is predicted that producers will shift away from GM products and source non-GM ingredients. The costs of labelling to the consumer in Canada are debated, but a large study in the US estimated that mandatory labelling would cost US$2.30 per person annually, not incorporating potential behaviour changes.

Mandatory labelling has a significant amount of public and political support, advertised as a means to give customers the ability to know what they are eating. The effect of mandatory labelling on consumer demand is debated: some argue that it will be widely perceived as a warning, thereby decreasing consumer demand for GM products. In response to consumer demand it is predicted that producers will shift away from GM products and source non-GM ingredients. The costs of labelling to the consumer in Canada are debated, but a large study in the US estimated that mandatory labelling would cost US$2.30 per person annually, not incorporating potential behaviour changes.

Another significant issue is the role of chemical companies and large corporations in agriculture. A small number of large corporations exercise ownership over a large and growing amount of food. Farmers cannot save and replant GM seeds; they must purchase them from the manufacturers. There are fears seed diversity will be negatively impacted, impacting food security.

Several Questions

Whereas today GM foods are primarily present in processed foods and animal feed, there is potential for the commercialization of many other GM crops. Efforts are underway to commercialize the non-browning “Arctic Apple”, GM alfalfa, wheat, and some species of fish. What would the effects be of the expansion of the kinds of GM crops being grown, especially for our ability to grow organic produce?

Whereas today GM foods are primarily present in processed foods and animal feed, there is potential for the commercialization of many other GM crops. Efforts are underway to commercialize the non-browning “Arctic Apple”, GM alfalfa, wheat, and some species of fish. What would the effects be of the expansion of the kinds of GM crops being grown, especially for our ability to grow organic produce?

GM crops have only been on the market since the 1990s, so the long-term effects on health and the environment cannot yet be conclusively known. Given the concerns regarding industry funding of scientific studies and the lack of long-term independent studies, many questions remain regarding the chronic and long-term effects of GM crops on human and animal health, and the environment.

Evaluation and Summary

Given the number and the extent of the unknowns associated with GM crops, precaution would suggest, at a minimum, mandatory labelling, an independent, peer-reviewed process to ensure the safety of GM crops before they are approved by government regulators, and long-term, well-funded independent studies on the effects of GM crop on human health and the environment. Mandatory labelling of foods containing genetically modified ingredients would enable people to choose if they want to consume GM foods and support GM technology through their purchases. It would also have the likely effect of decreasing demand for products containing GM crops, moving producers away from sourcing GM crops.

Labelling that specifies the nature of genetic modification (e.g. genetically modified for insect resistance; herbicide tolerance; vitamin A added) would differentiate between kinds of genetic engineering and make the information conveyed through labels more meaningful for consumers. Investigating the extent to which specific labelling is possible, what its challenges and costs would be, and whether there are best practices elsewhere, is suggested.

Industry is a significant source of funding for scientific studies on the health and environmental effects of GM crops, and the Canadian government does not independently review company studies on the safety of GM crops. Funding independent and long-term research on health, environmental, and other effects of GMOs would provide a trusted scientific source of information to inform policy going forward. The establishment of a national research program to monitor the long-term effects of GM organisms was recommended by the Royal Society of Canada expert panel to the Canadian government in 2001, but has not yet been realized.

It seems that many of the strongest motives for concern regarding GMOs come less from an issue with the technology of genetic modification itself, and more from the context in which it is taking place. Regulation and independent long-term research are lacking, and a small number of large chemical companies are driving forward a huge expansion of GM technology in the midst of many uncertainties and unanswered questions regarding its potential effects on our health and the health of our environment.