Voting for a Responsible Economic Future for B.C.

Today we had a critical vote concerning the government’s proposed LNG industry.

Both the NDP and the Liberals voted to move Bill 6 – the Liquefied Natural Gas Income Tax Act to committee stage. In doing so, they voted for what I believe is ultimately a Generational Sell-out – one which will cost us the opportunity to forge a new path to develop a 21st century economy for British Columbia.

I stood alone and voted against this bill because it is fundamentally irresponsible.

The government and the official opposition are going all-in on an LNG industry despite a highly competitive market that is many steps ahead of us here in B.C. To catch up, this Bill offers a suite of tax deductions, exemptions and ultimately taxpayer funded rebates to entice industry to invest here. The hope is that we will be able to buy ourselves an LNG industry.

What I worry about is how much it will cost our province. If the bill passes, we will essentially be giving away our natural gas resources in order to fulfill the Liberal government’s desperate and hyperbolic election promise.

Instead of this pipedream, we have an opportunity to pursue a truly 21st century economy, with new investments into education and social services, a focus on new and emerging industries already found in our Province, and taking legitimate steps forward to address our contributions to climate change.

The passage of this Bill does not mean the province will crumble. However, this approach to our economy risks passing on a substantial debt to the next generation – forcing them to bear the consequences and the costs of our inaction today. This is not leadership.

I will continue to advance the only alternative that has been offered to the government’s plans: my vision of a diversified, sustainable 21st century economy–one that will serve today’s generation without burdening generations to come.

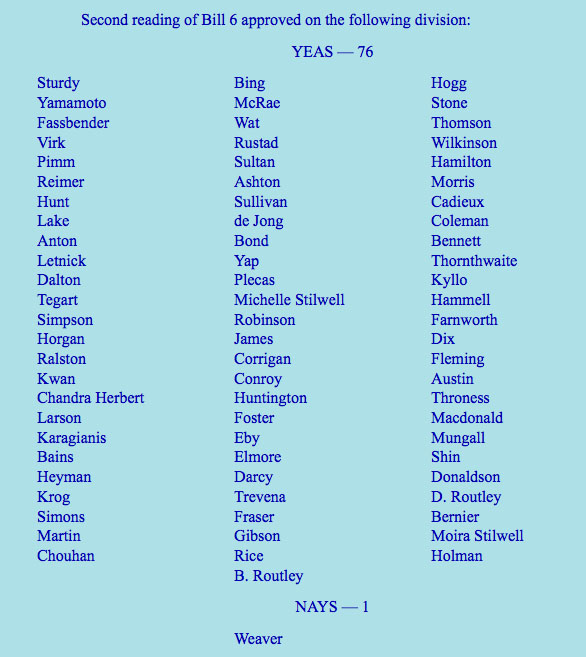

The Vote

Unpacking Trans Mountain’s “Credible Worst-Case” Oil Spill

This post is part of an ongoing series in which MLA Andrew Weaver will be sharing key information from inside the National Energy Board hearings on Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain pipeline proposal. To see previous posts, please click here.

Trans Mountain’s “Credible Worst-Case” Oil Spill

As part of their analysis, Trans Mountain conducted oil spill scenarios for what they consider to be “credible worst-case” and smaller-sized spills.

The purpose of running these scenarios is to estimate the likely impact a spill would have on our communities and our environment, as well as to gauge their ability to respond to a spill. The problem is, Trans Mountain’s “credible worst case” spill scenario only accounts for a small fraction of the oil that could actually spill.

Here’s what I mean:

A single oil tanker will carry over 110,000 tonnes of oil. Yet, according to Trans Mountain, the maximum size of a “credible worst case” spill (i.e. the largest spill they think could ever actually happen) would only be 16,500 tonnes. That’s only 15% of the oil carried by a single ship.

So where does their definition of a “credible worst case” spill come from?

Trans Mountain undertook a probability analysis, factoring tanker size, shipping lanes and traffic, as well as other data. They found that 90% of their spill scenarios were smaller than 16,500 tonnes in size. Trans Mountain then simply “defined” this to be their “credible worst-case” scenario. That is, they defined ‘credible worst-case’ as the 90th percentile.

That means there is not a single report or study in the entire 15,000 page application that considers what would happen if more than 15% of the oil on a tanker were to spill.

I found this profoundly troubling. In my first round of questions, I asked Trans Mountain to provide an analysis of the risks and impacts of having 100% of the oil spill. This is called a total loss scenario. While it fortunately isn’t a common scenario, it certainly does fall into the realm of possibility.

Unfortunately, Trans Mountain responded by saying that a total loss scenario was not “viable” or “credible”, that my request was therefore not relevant, and so refused to provide the sought after analysis. They base this on the fact that “there has not been any total loss of containment scenarios involving a double hull tanker, ever, to date…”

The Problem with Trans Mountain’s “Credible Worst-Case”

I have two big concerns with Trans Mountain’s logic.

First, the very fact that Trans Mountain’s “credible worst case” oil spill only accounts for 90% of spills means that there is a 10% chance that an oil spill will be larger than their “credible worst case”. 10% isn’t some distant possibility—it’s a very plausible scenario. In fact, the Exxon Valdez spilled roughly 35,000 tonnes of oil—more than double the size of Trans Mountain’s defined “credible worst-case” scenario. The Atlantic Empress released 287,000 tonnes of crude in 1979 after it caught fire and sank in the Caribbean. In 1983 Castillo de Bellver exploded off the coast of South Africa and released 50,000 to 60,000 tonnes of light crude into the sea. In 2002, Prestige split in half and sank off the coast of Spain releasing 63,000 tons. And of course, there are other examples. By refusing to even consider the possibility of these larger spills, they are ignoring spill scenarios that are certainly possible and that would have a devastating impact on our coast.

Second, while it may be true that so far no double-hull tanker has spilled 100% of its oil, this is far from a solid argument. The fact is, policies requiring all new tankers to be constructed with double-hulls are relatively new. It is only within the last 20 years that this has become a mandatory requirement. So, while a total loss incident involving a double-hull tanker has not occurred to date, these ships have not been in use long enough for such a justification to be made with much certainty.

This leads me to two basic questions:

How can Trans Mountain credibly say that they have provided a full analysis of the risks and impacts of marine oil spills, when they refuse to even consider the possibility of more than 15% of oil spilling?

How can British Columbians trust that Trans Mountain can actually clean up a spill, if the largest spill they are prepared for only accounts for a small fraction of the oil onboard?

If you ask me, they can’t.

Trans Mountain’s Oil Spill Economics

This post is part of an ongoing series in which MLA Andrew Weaver will be sharing key information from inside the National Energy Board hearings on Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain pipeline proposal. To see previous posts, please click here.

Trans Mountain’s Bold Claim

While reading through Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain pipeline application, my team was astonished to come across what has become one of the most talked about quotes from the entire 15,000 page application.

In discussing the impacts of oil spills, Trans Mountain tells us that “spills can have both positive and negative effects on local and regional economies.” Taking that point even further, they say that “spill response and clean-up creates business and employment opportunities for affected communities, regions, and clean-up service providers”

As you might predict, it didn’t take long for national and international news outlets to pick up on these quotes and for Trans Mountain to backtrack on their claims. According to them, the quote was taken out of context.

Given the serious and legitimate concerns we have about oil spills on our coast, I thought it was important to find out more about how Trans Mountain evaluated the potential economic impacts of a spill.

Requesting Trans Mountain’s Analysis

Now, let me first say that no economic benefits can justify the environmental catastrophe that a spill would cause. So many of our lifestyles, livelihoods and communities are based on the pristine coast we are so fortunate to have here in British Columbia. Not to mention the impact a spill would have on the environment itself, irrespective of our use of it. That is what makes Trans Mountain’s statement particularly troubling.

Yet, when it comes to this type of application, part of the process for weighing the costs and benefits of the pipeline also means analyzing the economic impact of a potential spill. Unfortunately, here’s what I found out from Trans Mountain:

In their entire 15,000 page application, Trans Mountain did not once adequately analyze the economic impact of a marine-based oil spill resulting from their project. Not only that, they told me they don’t need to do this. Here’s what they said:

“Economic cost-benefit analysis is an analytical tool sometimes used to inform whether a planned activity, policy or investment is beneficial to the economy and society. A spill is not a planned activity: it is an accident”. Therefore, “spills are not part of the economic benefits analysis undertaken for the project.”

If the economic impact of a spill is not analyzed in the application, then how can we know the true impact a spill would have on our local communities? And if we don’t know that, then how can we know the full extent of the risks we will be undertaking should this project be built?

A Look at the Research

Trans Mountain’s statement is based on what they say is a “growing body of literature” that “shows that both positive and adverse effects can occur” from a spill. So what does that literature say? According to one study:

“The McDowell Group (1990) report concludes that there are positive effects on spill-related business and certain business sectors such as hotels/motels, car/RV rentals, air taxi and boat charters offset negative effects on Vacation/Pleasure business.”

Most of these “positive effects” benefit businesses and sectors that help clean up a spill or that house temporary workers who would travel here to clean up a spill. Local economies, like our commercial fisheries or our tourism industry—an industry that thrives on the unique and unparalleled beauty of our natural surroundings—won’t be so lucky.

Not only that, but as it turns out, even this growing body of literature clearly demonstrates that the net overall effect of a spill is negative.

Of course, what Trans Mountain’s statements also ignore is the potentially catastrophic impacts a spill would have on the environment itself. There are few places in the world that offer as pristine a coastline and as beautiful an environment as we have here in British Columbia. To lose that to a spill would be simply devastating.

Trans Mountain’s failure to consider the full range of negative impacts that its pipeline could have on our local communities and on our environment reflects a mindset that is simply out of touch with the beliefs and values of countless British Columbians. It shows just how far Trans Mountain is from ever gaining the social license it needs to build its pipeline.

Determining the Scope of Trans Mountain’s Pipeline Consultations

This post is part of an ongoing series in which MLA Andrew Weaver will be sharing key information from inside the National Energy Board hearings on Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain pipeline proposal.

Consulting with British Columbians

One of the biggest stumbling blocks for Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain Pipeline is the question of whether there has been adequate consultation with British Columbians and with First Nations. Ultimately, this question is so critical that in many cases, it will have to be decided by the courts.

Indeed, Enbridge’s Northern Gateway pipeline proposal is already facing a number of court challenges from BC First Nations. They argue that they were not adequately consulted. They further argue that the company did not fully consider their opinions when they were consulted.

Trans Mountain is already caught up in similar legal action from the Tsleil-Waututh First Nation. The Tsleil-Waututh position is that the Federal Government has failed to consult with them about the pipeline proposal.

British Columbians have been clear that for any company to build an oil pipeline, it must first earn a social license for the proposed project. And earning that social license starts with consultation. I therefore spent quite a bit of time unpacking Trans Mountain’s consultation efforts in my first round of questions to the company.

Guidelines for Community Engagement

As a part of their consultation process, Trans Mountain defined guidelines for community engagement. These guidelines were generally referred to as the “scope” of the engagement process. They set boundaries and limitations for what was to be done during consultation.

Here is the scope of engagement for the project:

- Determining the scope of the environmental and socio-economic assessment (ESA);

- Identifying potential mitigation measures to reduce environmental and socio-economic effects;

- Identifying potential benefits associated with the Project;

- Routing alternatives where it is not practical to follow the existing Trans Mountain Pipeline System right-of-way.

Finally there was also a guide to future consultations that stated:

“Future consultation plans will include providing communities with information on pipeline integrity, safety and emergency response; a topic that has been raised in many communities”.

Breaking down the Guidelines

The first thing that hits you after reading this, is that all the guidelines for engagement assume that the project will be built, regardless of what people say. They simply ask about how the project should be built, not if it should be built. Why didn’t Trans Mountain ever ask people if they thought the pipeline should be built in the first place? Is that not a fair question?

When I asked Trans Mountain about this in my first round of questions, they replied by saying that the scope of their engagement does not limit them from going further to consider other issues.

While that sounds great in theory, in practice it is very problematic.

The whole reason scope exists is to provide limitations on what can be considered. For example, Trans Mountain refuses to answer questions about climate change and the Alberta tar sands during the hearing process. They say such questions are outside the scope.

The fact is, you can’t have it both ways. Trans Mountain cannot continue to refuse to answer questions because they are ‘out of scope’, but then claim that they can consider anything, regardless of whether or not it is ‘in scope’.

I think you will agree that it’s critical that questions about what falls inside or outside of scope are adequately addressed now, in order to properly evaluate how consultation was conducted.

An inclusive and transparent engagement process that is accessible to all British Columbians is the only way large industrial projects are going to be able to proceed in British Columbia.

Kinder Morgan’s “Casualty Data Survey”

This post is part of an ongoing series in which MLA Andrew Weaver will be sharing key information from inside the National Energy Board hearings on Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain pipeline proposal.

Many British Columbians are concerned about the risk of an oil spill on our coast.

That’s why my team and I went through the oil spill risk analysis provided in Kinder Morgan’s application. We wanted to see if the evidence Kinder Morgan offered gave British Columbians an honest take on the risks of this project.

There are a lot of sections to Kinder Morgan’s risk analysis—some are done quite well, others are deeply concerning. I will write more about these over the coming months.

Today, I would like to look at one report in particular. It offers a good example of the concerning way in which Kinder Morgan is approaching the review process.

Casualty Data Survey

As a part of its application, Kinder Morgan submitted a report done by Det Norske Veritas (DNV) titled a “Casualty Data Survey”. The report looked at the frequency of incidents involving oil tankers and compared the results to other types of vessels, such as chemical tankers and bulk carriers. Overall, the report is quite informative and gives a good sense of the frequency of incidents, including spills.

What is concerning is not the report itself, but the highly questionable conclusions that Kinder Morgan draws from the report. Let me offer an example:

In its pipeline application, Kinder Morgan makes the claim that “based on the available data, DNV shows that worldwide incident frequency involving oil tankers is among the lowest of all marine vessels for the period 2002 to 2011…”

I thought this was important, so I decided to ask about it.

Questioning the Claim

First of all, I found this claim interesting, since DNV only appeared to compare oil tankers with three other types of vessels: LNG-LPG Tankers, Chemical Tankers and Bulk Carriers.

I asked what data was theoretically available for comparison. It turns out that data was available for 19 different types of vessels. Kinder Morgan chose to only compare four types (including oil tankers) because it felt they provided the best basis for comparison.

That could be a fair judgment to make. But when they have only compared 4 of the 19 vessels types, they cannot then make the assertion that they have compared oil tankers to “all marine vessels”.

What makes it worse is that oil tankers don’t actually have the lowest number of incidents when compared to the other three vessel types. Oil tankers have the second highest frequency of “total loss” incidents (damaged beyond repair) and the third highest rate of “serious incidents”.

I asked Kinder Morgan to justify their claim in light of this evidence. In their response, they reiterated that their conclusion is “accurate”, but failed to address the contradictory evidence.

My Concern

Ultimately there is a bigger issue here than simply how an oil tanker compares to other marine vessels.

My concern is that this example is indicative of a trend we are seeing from Kinder Morgan. The company has made claims that are unsubstantiated by the information it provides in its application. When intervenors ask about these claims, Kinder Morgan avoids the question or refuses to give a clear answer.

An effective review process is predicated on openness and honesty. I am concerned that we are not seeing enough of either from Kinder Morgan.