Introduction

Over the fall, we have explored the concept of basic income in a series of posts on my website, asking for your feedback on each post. The responses I have received, through comments on the website and my Facebook page, as well as in calls and emails to my office, have shown me that there is significant interest in the idea. The reaction has included high levels of support and enthusiasm, as well as a number of concerns and questions.

Your comments and our research have informed our proposal for moving forward with exploring how basic income could contribute to building a better future in BC. In this final post I will summarize what our series has explored so far, and why we should consider basic income as a tool to help us rectify some of the problems that we face today in BC, and those that we may face tomorrow.

The status quo in BC

After a general introduction to the concept of basic income, our second post in the series discussed what poverty looks like in BC, the social assistance programs available and how they can fail to help those most in need. It also explored how basic income could help to alleviate poverty in our province. We know that BC has higher rates of poverty and child poverty than the national average: poverty stands at 11-16% and child poverty is even higher, at 16-20%, depending on the measure used. We also know that poverty is not spread evenly across population groups and regions in BC. Amongst lone parent families, for example, 50% of children live in poverty; aboriginal people, immigrants, and people with disabilities are also more vulnerable. Some regions are disproportionately affected: on the Central Coast, for example, the child poverty rate is above 50%.

After looking at poverty and social assistance in BC, we focussed on the trends we are seeing in the world of work: the rise in precarious employment and the trend towards increasing automation of jobs. Our third post outlined the shift we are experiencing as a population away from long-term, full-time work with benefits, toward short-term, part-time, and contract-based work. Federal Finance Minister Bill Morneau said recently that Canadians must get used to “job churn”, and this is a national trend that BC has not escaped: 75% of jobs created in the last year have been part-time. This situation has left many with significant financial insecurity, juggling part-time jobs, struggling to make ends meet, and worrying about an uncertain future.

We also examined the increasing automation of jobs. Many studies predict that automation will eliminate a huge number of jobs across a range of sectors: one study, for example, predicts 47% of jobs are at high risk of computerization over the next 20 years. Jobs in manufacturing, transportation and warehousing, and office and administrative support are widely cited as the most susceptible (see here and here, for example). The impact on BC of job losses in these sectors would be very significant: the transportation and warehousing sector employs 140,000 people, while manufacturing employs 168,000, down 12,000 from a year ago. Already BC is one of the most unequal provinces in Canada, a problem that automation would exacerbate as it replaces mostly moderate-paying jobs and concentrates the benefits in the hands of a few beneficiaries.

Automation is an issue that those in the technology industry are taking very seriously: Amazon’s chairman, Jeff Bezos, has said “It’s probably hard to overstate how big of an impact it’s going to have on society over the next twenty years.” Yet despite widespread acknowledgement that automation poses a serious threat to our workforce and could have widespread social implications, it does not seem that our government is considering the seriousness of the issue. As politicians we have an obligation to take the threat of automation seriously and prepare for the possibility of a future in which the world of work as we know it is fundamentally altered. We cannot be left playing catch-up, merely reacting to the moves of industry and the development of technology, and rushing to create policies to mitigate the adverse consequences after they have already taken hold.

Recommendations

Already, the economy in BC is not working for many. Despite our wealth as a province, and the many resources on which we can draw, many people in our province face substantial financial insecurity. While we have seen economic growth and the Province projects a budget surplus of $2.24 billion, we have poverty levels that have remained unchanged for years, welfare rates that haven’t increased since 2007 and that leave recipients well below the poverty line, cities that are increasingly unaffordable, and unprecedented rates of food bank use. This is a reality that we have the opportunity, and the obligation, to change.

Moreover, simply raising the minimum wage is not an adequate answer, given the changing conditions in the world of work. A higher minimum wage alone fails to provide financial security to those affected by the rise in precarious employment, as you only benefit to the extent that you maintain stable employment with sufficient hours, something that is becoming unattainable for more and more people. Furthermore, it does not respond to the threat of automation. You need to have a job in order to benefit from a higher minimum wage, so it does not help people made redundant due to automation. Combined with the increasing ability of companies to automate, a higher minimum wage alone also runs the risk of accelerating the drive toward automation, by making humans relatively more expensive than their robotic counterparts.

Basic income could be an effective tool to tackle the persistent, intergenerational poverty we see in BC, and the shortcomings of our current social assistance programs. It could also help those who are suffering from the rise in precarious employment by providing some measure of financial security, and preventing those on the edge from slipping into poverty due to inadequate hours or job transitions. It could also provide a means to make up for the structural unemployment and inequality created by automation, and keep the economy going by providing people with purchasing power. Moreover, basic income has more visionary potential: it could provide people a stable base on which they can take entrepreneurial risks, pursue further education or retraining, or spend more time doing work that is essential to our society but is not financially rewarding, such as taking care of family members in need. It could therefore improve our wellbeing as individuals, and our resilience as a society.

To achieve these goals, a basic income would need to be high enough to raise individuals and families across the Province above the poverty line. To be affordable, it would likely need to be conditional on income (i.e. not a universal basic income to all individuals regardless of income, but rather a targeted payment to those who fall below a determined threshold). It would also need to take into account the differences in the cost of living across BC, to ensure that people are not consigned to poverty in our cities.

Basic income holds exciting prospects for improving the lives of many in our Province and securing us against an uncertain future. However, it is important to recognize some of the uncertainties inherent in the idea and respond to the concerns raised by a number of people who have commented on previous posts.

The most common question is whether basic income would provide a disincentive for people to work. Would basic income encourage people to leave the workforce, or discourage them from joining in the first place? Or, on the other hand, would it provide a safety net, and a level of autonomy necessary to encourage entrepreneurship, retraining, and the pursuit of educational goals? What would be the overall balance in a community? Would there be an effect on young people specifically? The question of how basic income would affect people’s choices about working is difficult to answer in the abstract, and we have limited real-world experience from which to draw. The Dauphin, Manitoba pilot found that the negative effect on people’s willingness to work was negligible for the general population, but more pronounced for mothers with young children, as well as school aged teenagers from low income families, who completed high school instead of leaving to join the workforce. The question of cost has been the second-most discussed issue. What would be the net cost of basic income? Would basic income create an inflationary effect? How would the social benefits translate into cost savings? Which social programs could be streamlined or eliminated, and which supports would need to be maintained, perhaps in an altered form?

Pilot Projects

The need to answer these questions, and others, leads me to conclude that pilot projects are a necessary step in considering implementing basic income in BC. A policy change of this magnitude has significant associated opportunities and risks, many of which cannot be quantified in the absence of real world results. Pilot projects would allow us to test how such a policy could be rolled out effectively, calculate the net costs, and measure the outcomes on families, individuals, and communities in BC.

A number of other jurisdictions are undertaking pilot projects. Finland and the Netherlands are both staging pilots in 2017, while the charity GiveDirectly is staging a pilot in Kenya. In Canada, Ontario is currently undertaking community consultations to inform their roll out of pilot projects in 2017: they are designing their pilots to determine whether basic income would be more effective than their current social programs in lifting people out of poverty and improving health, housing and employment outcomes. Quebec has also shown considerable interest in basic income. And earlier this month, MLAs in PEI voted unanimously to approve a motion calling for developing a basic income pilot project in partnership with the Federal Government. There is no reason why BC should be left behind in the move to test this idea.

To be effective in tracking the effects of basic income on some of the most pressing problems facing BC, including poverty, inequality, and economic change, the places selected for pilots should be particularly affected by these issues. Places such as Port Alberni and Prince Rupert provide examples of potentially appropriate sites for a pilot. One pilot site should be a relatively small town, to enable saturation in order to measure the effects on the community as a whole, as well as on individuals and families within that community. The project would likely need to be at least five years long, in order to enable us to measure the poverty, health, education and employment outcomes, and to calculate the net cost of such a program, taking into account the social benefits that accrue over time. We would seek the partnership of the Federal Government in testing basic income, as PEI has decided to do. We would also need to create residency requirements to avoid a large influx of people into the pilot site.

Beyond these fundamentals, a committee that is independent of the governing party should be established to undertake further analysis of basic income, to hold community and stakeholder consultations, and to advise on the details of how pilot projects should be designed and implemented. There are a number of specific issues that need to be investigated, such as: parameters for tax rates on earned income above the basic income threshold; interactions with other social programs and supports; how to mitigate risks to vulnerable groups; and how to incentivize the pursuit of education as well as paid and unpaid contributions to society.

Conclusion

We must address the unacceptable levels of poverty and inequality in our province, mitigate the adverse consequences of the rise in precarious work, and prepare for a future that may bring fundamental economic change through technological advance. To address these challenges we must create forward-thinking policies, informed by a commitment to a more equitable future and strong evidence on how to get there.

Basic income could be one such policy. It could help us alleviate poverty, foster healthier families and communities, encourage entrepreneurs and volunteers, enable education and retraining, and allow British Columbians dignity and autonomy while they navigate a changing world of work. With the right tools and foresight, and guided by evidence all the way, we can support a 21st century economy that is resilient, and craft a future that works better for everyone.

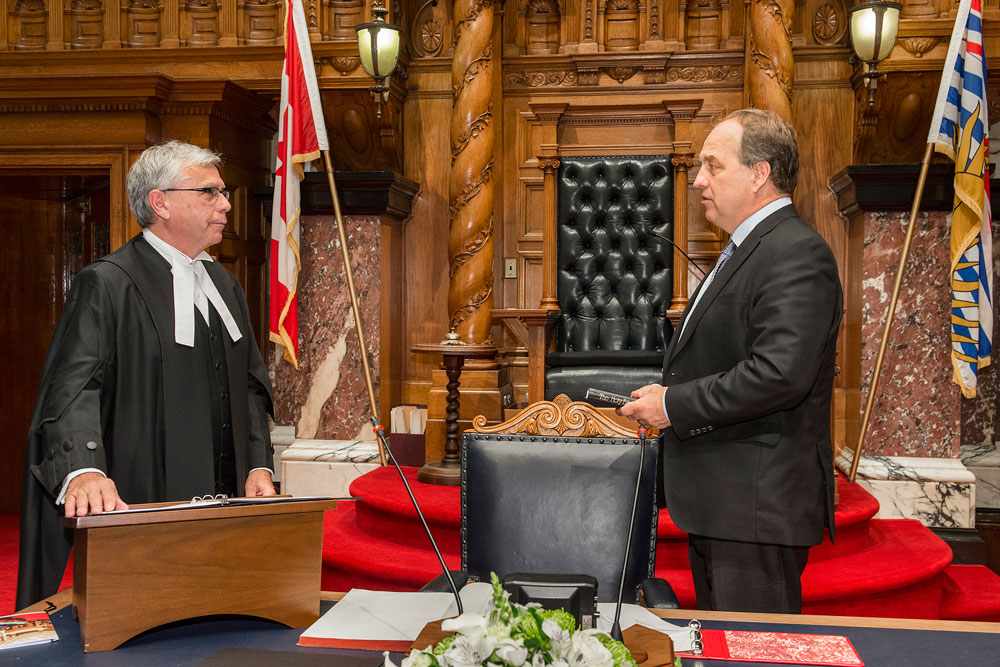

As premier in a BC Green government, I commit to introducing pilot projects that explore the costs and benefits of basic income.

I continue to welcome your comments, particularly if you haven’t yet had a chance to share your thoughts on basic income and the role it could play in BC.