Issues & Community Blog - Andrew Weaver: A Climate for Hope - Page 156

Probing Jurisdictional Rights and Responsibility Regarding Air Quality in Metro Vancouver

Last week I sent a letter to Minister Anton hoping to clarify the province’s role in Fraser Surrey Docks’ ongoing court case. The company is disputing a ticket issued by Metro Vancouver and the court’s decision could have significant consequences for Vancouver and the province as a whole. Below is the text of the letter. I await a reply.

Letter to the Minister

April 22nd, 2015

Honourable Suzanne Anton

Minister of Justice

Parliament Buildings

Victoria, BC

V8V 1X4

Dear Minister Anton:

I am writing to you with regards to the ticket issued to the Fraser Surrey Docks LP for air contamination and the ongoing trial disputing the fine.

As you know, the maintenance of air quality is generally the purview of the province and government has decided to partially delegate this responsibility. Under the Environmental Management Act, passed in 2003, the Greater Vancouver Regional District is able to, “by bylaw, prohibit, regulate and otherwise control and prevent the discharge of air contaminants.”

On October 3rd, 2013 the regional district used this power to issue a $1,000 fine to the Fraser Surrey Docks LP for the discharge of an air contaminant, in this case soybean dust. This fine was disputed by the company, arguing that because they operate within the boundaries of Port of Metro Vancouver they are beyond the jurisdiction of regional, and by extension provincial, authority.

Serious concerns have been raised over the implications that this case could have. Locally, a decision in favour of Fraser Surrey Docks could affect Metro Vancouver’s ability to maintain clean, breathable air in its jurisdiction, as air contaminants do not adhere to provincial and federal boundaries.

Secondly, there have been concerns that the legal decision could have ramifications that go far beyond the port itself. The maintenance of air quality is a responsibility shared by all levels of government but it primarily falls within provincial jurisdiction. A decision in favour of Fraser Surrey Docks could undermine the province’s ability to set air quality standards for other federal lands, including ports and pipeline corridors.

With this background in mind, I would like to submit the following questions:

- What is the government’s position on the validity of the ticket (#006035) issued to Fraser Surrey Docks LP by the Greater Vancouver Regional District for the discharge of air contaminants?

- In your government’s opinion, how far reaching are the powers surrounding air quality that you have delegated to the Greater Vancouver Regional District? Do they include federal port lands?

- What is the historic and current involvement of the province in this case?

- Following question three, does the province have any plans to either remain involved or get involved in this case in the future? If so, what are these plans?

I look forward to the Minster’s response to my questions and hope that it will shine more light on this issue.

Sincerely,

Andrew Weaver

MLA Oak Bay-Gordon Head

Why I am opposing Bill 20: Election Amendment Act

In the coming weeks, we will be debating Bill 20: Election Amendment Act. I recently did an interview on BC1 Unfiltered which outlines the reasons why I will be opposing the Bill.

The BC1 Interview

Samantha Falk was stepping in for Jill Krop in the interview.

Bill 23: An Act of Desperation

Last week I wrote about the very serious concerns I had with Bill 23, The Miscellaneous Statutes Amendment Act. Today I spoke against the Bill at second reading. Included within the bill are three profoundly troubling sections and below I outline my objections to these in greater detail.

I begin my speech by discussing what can only be described as one of the most bizarre moments for me in the Legislature since being elected. It has to do with the government promising, in their throne speech, to create a medal that already exists.

I then move to outline a number of outrageous steps that government is taking in a desperate attempt to land a single positive LNG final investment decision. It is truly remarkable to witness how desperate government is becoming. Sadly, government’s attempt to fulfill their irresponsible election promise of wealth and prosperity for one and all from a hypothetical LNG industry is coming at the expense of future generations.

Video of Second Reading Speech

Second Reading Speech

A. Weaver: Thank you to the previous speakers for highlighting some of the issues I too would like to speak to, and against. in similar cases.

First off, I do wish to thank the Minister of Natural Gas Development for making staff available for a briefing today, which we found very helpful in explaining some of the rationale behind the royalty amendments that I will discuss later.

As was mentioned by the member from Nanaimo, this Miscellaneous Statutes Amendment Act, like previous acts, is always interesting because there’s a potpourri of topics in here, some of which some members in this House will approve. Others, some members in this House will not approve. There’s many different angles that one could take with this bill. In voting yes or no on the second reading, one has to weigh the pros and the cons. One might actually think that the ways of dealing with some of these are at the committee stage, which I certainly will explore in more detail, some of the ideas there.

There are a couple of sections that concern me quite profoundly. But I will start, and I want to preface that there is one section here that is actually good and something that I find very easy to support, and it’s an election promise that the B.C. Liberals will be able to keep. The irony here should not be lost on many people.

I’ve had the privilege of serving in this Legislature for two years. In that two years I’ve heard a lot about the 1990s. I’ve heard it referenced time and time again about what happened in the 1990s. Well, did you know that in the 1990s, the Provincial Symbols and Honours Act was brought in place?

Guess what is there in section 19 of that act. Section 19 states this: “The Lieutenant Governor in Council may award the British Columbia Medal of Good Citizenship to recognize persons who have acted in a particularly generous, kind or self-sacrificing manner for the common good without expectation of reward.”

This was one of the prime announcements in the throne speech — that government would actually bring forward a B.C. Medal of Good Citizenship that already exists. This has got to be one of the most bizarre moments for me in this Legislature, to see the hubris, the narcissism of a government that thinks that it’s okay to make a big deal about bringing in a medal that’s been on the books for almost 20 years. It’s truly, truly…. I mean, you can’t make this stuff up. It’s happening in B.C. politics here in the House

You know, what is so sad about this is that British Columbians are paying the price. British Columbians are paying the price for a government that clearly does not have an legislative agenda this session, apart from desperately trying to fulfil its election promise about LNG.

We watch one after another after another of the big players in the LNG market cite what I have been saying for two years: the growing glut of natural gas. The price is dropping. Japan is bringing on nuclear reactors again. Australia is well ahead. Companies are merging. The price of oil is dropping. And B.C., rather than recognizing that we are late players in this game, that we do not have a competitive advantage, that we will maybe one day find a use for this natural gas….

I see some small little additions here, which I call the methanol and the refining amendments, where there are some kinds of ideas that perhaps we should do something in case it doesn’t pan out, and there are other projects that we might go for. What this government is doing with amendments, two of them in this act, is continuing this generational sellout which my friend from Nanaimo–North Cowichan and I describe as a generational sellout. I cannot take credit for the term “multigenerational sellout.” That goes to the member for Nanaimo–North Cowichan. But it’s far beyond that.

We see this taking another step. Not only are we letting the minister enter into royalty agreements that will hamper future generations, not only government but future generations, by irresponsible promises made by a government that had no idea what it was doing during an election campaign except for offering a message of hope wrapped in hyperbole in a desperate attempt to get elected.

“Say anything. We’re not going to get elected, but let’s hope we get a few seats.” And lo and behold, we have a majority over here, a government that does not know what they’re doing on this file and that has become an embarrassment internationally on the LNG file. We’ve watched company after company after company look at us and say: “What’s going on?”

Here we now have, in this bill, the greatest, most serious insult that future generations could have, which is saying: “We are going to lock you into royalty rates with one company. We’re also going to forget municipal charter acts.” We’re going to go over that too, and we’re going to do what we can to write legislation so that this one company may — may possibly, perhaps — if things go well, make an investment decision by June of this year. And they’re the only one thinking of doing it.

The level of irresponsibility here — I cannot underestimate it. British Columbians should be walking in the streets over this legislation. I know they’re not going to pay attention to miscellaneous statutes amendment acts. Buried within that is not only an intergenerational or a multigenerational sellout, it’s a historic one. It’s a historic sellout to foreign multinationals of the rights of British Columbians and future generations to gain value from our natural resources.

It’s a very sad day in British Columbia if we were to pass the relevant sectors in here. Sadly, as this government no longer listens to constituents, to small business owners — we see it in the liquor legislations — to the opposition, to independent members, they are marching to the beat of their own drum, because they think that by being elected as a majority they have carte blanche to do whatever they want, with no accountability.

But there will be accountability when British Columbians do realize this, and we can see it happening around the province. There will be accountability in 2017 for this multigenerational, historic sellout that is continuing here in British Columbia.

Let’s move directly to section 23, the Port Edward tax agreement. Now, where is this coming from? The Port Edward tax agreement. For those riveted at home to the debates that are happening now, Port Edward is near Prince Rupert. It’s where Petronas and BG and Shell…. It’s in the area where there was going to be an LNG facility.

It’s an area where there used to be a vibrant pulp mill, but of course that shut down because we’re not nurturing our forest industry; instead, we’re natural gas. It’s LNG or nothing in B.C. right now. It’s a message that’s being sent to business in B.C. I recognize the minister is troubled by those words, but the reality is business in B.C. has heard the message: you’re either with us on LNG or we’re not interested in where you’re going.

That is the signal, because the government here is picking winners and losers in the marketplace — a so-called free enterprise government picking winners and losers in the marketplace. The winner they’ve picked is LNG. But it’s even worse than that. It’s not winners and losers; it’s winning companies and losing companies, because we see legislation at the scale of individual municipalities. We’re amending the Municipalities Enabling and Validating Act to allow the district of Port Edward to enter multi-year agreements with Pacific NorthWest LNG.

What is going on here? We’re introducing law so that a municipality can forget the rest of the law that’s applied to municipalities in the province so that they can negotiate and do special deals with one company. We’re picking the winning technology and the winning sector, and we’re picking the winning company.

This is no longer a government that has any credibility as a free enterprise government. This is a government that is really a pick-a-winner-and-loser government. They’re picking losers as we go along, and it’s continuing to manifest itself with this legislation.

To be able to have this agreement last up to 25 years and establish an amount or formula to be used for the duration of that agreement for one company may give business certainty for that one company. Sure, Pacific NorthWest is going to have business certainty, and we all know business needs certainty, but this is giving an intergenerational sellout at the same time.

There’s no certainly for British Columbians here. This government was elected to represent British Columbians, not elected to represent Pacific NorthWest natural gas and Petronas and market that company to British Columbians, which is what is happening here in this legislation.

There are many other examples in this. I have another couple on this particular section.

You know, we see Port Edward being given the power to set a unique tax rate for Pacific NorthWest LNG that could be different from other class 4 properties. No, we’re picking one company over another. You want to develop this land, your class 4 property? Guess what. If you’re LNG, it’s one thing. If you’re forestry, you’re another. This is sending a message to industry that you are either…. You want to do industry in B.C.? You’re with LNG. We’ll do anything we can for you. But if you’re a struggling industry in another sector, maybe not. It’s LNG or nothing here in British Columbia.

A government that has the audacity to claim leadership on climate. The audacity for a Premier to be invited by the World Bank and to claim, in this province, that she is leading a government that has leadership on climate policy does nothing but make the government of British Columbia a laughingstock within credible people across Canada.

This government has no credibility on the issue of climate policy. It was the previous administration, under the leadership of Mr. Campbell and the leadership of Barry Penner, the Environment Minister, that built that credibility that this government has destroyed in the matter of two-and-a-half short years.

Now, I recognize the Minister of Health did his bit. He was a very fine Minister of Environment when he was there, but he’s no longer there. The Minister of Environment is doing what she can. Unfortunately, they are but a few within a caucus of many who are doing everything they can to unravel the leading climate policy that existed in this province.

Interjections.

A. Weaver: The truth does hurt. When the members opposite start heckling, they recognize that the truth does hurt — the truth to try to claim leadership on greenhouse gas emissions.

Interjection.

A. Weaver: The Minister of Health suggests I’m losing credibility by telling the truth. I would suggest to the minister that the government has lost credibility by not telling the truth for two years.

You can check my page: andrewjweaver.ca. It’s there from December 2012. That’s on Facebook prior to the election and during the campaign. I’ve said the same thing about LNG. I haven’t changed my tune. The government has — a $100 billion prosperity fund, a $1 trillion hit to GDP, “Debt-free B.C.,” no PST, thriving schools and hospitals. La, la, la. Come to B.C. We’ll tell you what you want to hear, not what you need to hear. Unfortunately, here we are in B.C. with yet another generational sellout happening before us.

Subsection (4)(b) exempts agreements from cabinet regulations that prescribe limits on tax rates, relationships between tax rates, formulas for calculating tax rates and so on.

Section (4)(c), another exemption for PNW properties, allows an exemption for them being prescribed as port land under the Assessment Act. That, again, means that cabinet regulations that prescribe the actual value of the port land — or they establish rates, formulas, rules or principles for determining the actual value of the port land — would not apply. Let’s just throw that out. It might not give a company certainty.

Subsection (4)(d) exempts PNW properties under an agreement from the Ports Property Tax Act. We wouldn’t want to tax LNG, which generally outlines property tax provisions for ports.

Whose needs are actually being served here? Is it British Columbia’s needs? Is it this government that is voted and tasked to represent British Columbians and provide the oversight that British Columbians want? Or is it the winner that they chose in the winning sector, in an economy, in a market that’s falling? When other jurisdictions are diversifying their economy, we are not.

The Community Charter was written to provide fairness and a level playing field for businesses. This act seems to empower Port Edward to create an unfair playing field.

It gets worse, with the royalty agreement section in sections 44 to 56. Sections 44 through 66 have received a lot of focus already, as they appear to be particularly troubling. They appear to allow the minister to enter into royalty agreements with natural gas producers. The minister can enter into an agreement without approval from the Lieutenant-Governor-in-Council if the agreement is “in respect of a prescribed class of agreements” — whatever that means.

There are several concerning points here. The entire purpose of this section appears to allow this government — a government that’s lost credibility on the LNG file, if it ever had any in the first place — to lock future governments into royalty agreements without offering as much as any way of oversight or checks and balances to protect British Columbians from, frankly, irresponsible decision-making that is ongoing in British Columbia today on this file.

We already have a royalty regime in place. The problem, of course, is that as far as the government is concerned and, perhaps, the industry is concerned, this royalty regime may not be certain in future governments. Perhaps the government is worried. Perhaps the government is worried that in 2017 the B.C. Green Party will be sitting over there, and they’ll be sitting over here. There’ll be a lot of my friends to the right over there and a few of you over here.

Perhaps they’re worried about that, and they want to give Petronas, or PNW, some certainty by locking in 25-year royalty rates at some rate that is to be prescribed at some point by a minister, if he or she wants, with some consultation — maybe, maybe not. Who knows? Because we’re not going to be actually bringing this forward in a very public fashion.

You know, the powers that have been given to the minister in this amendment act with respect to royalty creation in the natural gas sector are enormous. Not only are they enormous, they’re enormous powers to one minister — not the minister in the next government or the government after that but the minister in this government, a minister who’s part of the government that is so desperate to fulfil their irresponsible election promises.

The media are not going to…. They’re going to start probing. They may have given the government a few years of grace on this, but mark my word, when people start looking into this, it’s going to come a cropper if it’s not already starting to. This is egregious — what’s going on in this particular amendment.

Under the changes, the minister also has to disclose information that would be required to be disclosed under the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act. However, the section in here does not clarify who determines if the information needs to be disclosed or not. Is it an independent body that’s at arm’s length from the ministry? Or could the minister theoretically decide what should be or should not be disclosed? It’s not clear.

There are other aspects of this act that I’ll just very briefly speak to, that I’d be interested in exploring further at committee stage. That’s with respect to the oil and gas activities changes, section 48, where we have (e.1) and (e.2) to include two types of oil and gas activities, and these are “the construction or operation of a manufacturing plant designed to convert natural gas into other organic compounds” and “the construction or operation of a petroleum refinery.”

Again, it’s seeming to me, in light of the fact that I know of one proposal that’s been brought to government on (e.1) and one proposal that has been brought to government on (e.2), the government again is going forward and trying to pick winners and losers in a marketplace before actually letting the market decide who those winners and losers should be. I’m curious about what the government is intending here, and I will, indeed, speak to it at committee stage.

With that, I do thank you for the time. I look forward to further discussions in committee stage. At this point, I’m still in a quandary, with respect to the vote at second reading, not because I support everything in it, but I’m not sure at this point and I still need time to reflect on whether or not the merits of supporting it at second reading or not supporting it at second reading are more on the positive or negative.

Clearly, the egregious royalty and Port Edward changes that are the government desperately trying to pick winners and losers in the marketplace to fulfil election promises are unsupportable.

Obviously, I support the B.C. Medal of Good Citizenship — again. It’s already been on the books for nearly 20 years, and the irony of this…. Again, it’s one of these priceless moments that you get in this place, in the Legislature, after listening as an independent here for two years to “in the 1990s this” and “in the 1990s that.”

Well, one of the things that happened in the 1990s is that this B.C. Medal of Good Citizenship was brought into place. Obviously, I support that. Obviously, there are other aspects in this updating of various acts that I support. But these two changes are very, very troubling.

With that, I’ll pass and look forward to hear the continuing debates.

Bill 22: Special Wine Store Licence Auction Act

On Wednesday, April 22 (Earth Day) I rose to speak to Bill 22: Special Wine Store Licence Auction Act. This Bill provides government with the legislative power to create an auction for wine licenses in support of a wine-on-shelves in grocery store model. In my opinion, this bill creates a multi-tiered system that preferentially favours large grocery chains over small business. It is following a similar pattern to what we are seeing emerging with government legislation. It’s a pattern that is putting more and more power in the hands of the minister to do whatever he or she wants to do, with little legislative accountability. The only reason this legislation is being brought forward at all is because the auction “bids” that government receives are ultimately defined as a “tax” whose collection requires consent of the legislature.

To give a specific example of how this bill might hurt small business, we have to look no further than the locally-owned Peppers Food Store in Cadboro Bay Village.

In 1962 John Pepper opened a Shop Easy grocery store at the location. In the early 80’s John Davits and his partner bought the store after working in the meat department for Mr. Pepper. Once they took ownership, the community voted on a new name and it was renamed Pepper’s Food Store. John then became sole owner in 1990, although he has been either employed there or owner for over 35 years. Currently, he is in the process of turning over the day to day operations to his son, Cory, who has worked at the store in many capacities for over 25 years. Peppers is a grocery story with an area of 7,500 square feet. It does not qualify as a “grocery store” under the government’s definition that a “grocery store” referred to in the act has an area of at least 10,000 square feet. Peppers Foods owner John Davits publicly expressed concern over the fairness of this Bill. I concur.

Of course Pepper’s isn’t the only grocery store in Oak Bay-Gordon Head that doesn’t qualify. For example, the local grocery store that my family and I get most of our groceries from is Mount Doug Market owned by Carol and Cori Lau (it’s walking distance from our house). They too have an area less than 10,000 square feet yet they too only sell groceries to local residents.

This legislation grants government regulatory power to prescribe “…the number of special wine store licenses in respect of which bids may be accepted under this Act.” In essence, claims made in the media that there will be no new licenses are certainly not evident from this act. The legislation exempts “grocery stores” that win an auction license from the “one-kilometre rule” (prohibiting “store within store” grocery store liquor outlets being established within one kilonmetre of an existing distributer).

Here I worry about the Tuscany Village Metro Liquor store that has developed an excellent reputation for it’s special focus on wine, especially BC VQA wines. There are three larger grocery stores very close by that could undercut their market significantly, especially in light of the special pricing specialty wine store license auction holders are entitled to. Locally-owned small businesses are being unfairly treated. This is not right and I am absolutely bewildered why government wouldn’t ensure that small business in our community is protected. Small business in the engine of our economy.

Finally, the fact that these specialty wine store licenses restrict grocery stores to carry BC wine, cider or sake on their shelves may not be allowable under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). If we look specifically at Annex 312 of NAFTA it seems pretty clear to me that this act is simply not going to stand up to a NAFTA challenge. I wll be raising this at committee stage when we continue debate on the bill next week.

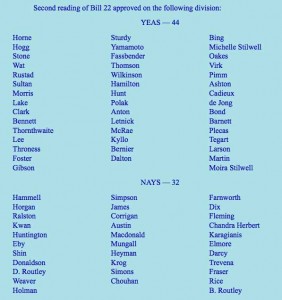

I was not alone in opposing the Bill as is evident in the second reading vote below.

The Vote

Congratulations to Sherri Bell on becoming Camosun College president

Media Statement: April 23, 2015

Andrew Weaver Welcoming Appointment of Sherri Bell as Camosun College President

For Immediate Release

Victoria B.C. – Andrew Weaver, MLA for Oak Bay – Gordon Head and Deputy Leader of the B.C. Green party welcomes the appointment of Ms. Sherri Bell as the new President of Camosun College. Ms. Bell has served as the Superintendent of School District 61 since March of 2014 following the retirement of John Gaiptman, She brings a wealth of experience to her new position from both the K-12 and post-secondary levels including time as principal in Lake Cowichan and James Bay Community School in Victoria, and as an instructor and practicum supervisor at the University of Victoria. Since 2001 she has worked in administration in the Greater Victoria district.

“This is tremendous news for Camosun College and the Greater Victoria community” said Andrew Weaver. “Sherri Bell is an outstanding and inspirational educator and administrator. Her professional achievements and experience will be a fabulous asset supporting the extraordinary work of the students, staff and faculty at Camosun and I congratulate Sherri on what really is a distinguished appointment”

Sherri Bell will be taking over from interim President Peter Lockie.

-30-

Media Contact

Mat Wright – Press Secretary, Andrew Weaver MLA

Mat.Wright@leg.bc.ca

Cell: 1 250 216 3382