Energy and Mines

Welcoming focus on climate leadership, but seriously, LNG?

Media Statement – May 12, 2015

Weaver welcomes focus on climate leadership, but seriously, LNG?

For Immediate Release

Victoria, B.C. – Andrew Weaver, MLA for Oak Bay-Gordon Head and Deputy Leader of the B.C. Green Party welcomes the government’s focus on climate leadership but is concerned that the government is putting LNG and a credibility-building exercise ahead of real action.

“The BC Government already knows what we need to do to address climate change. Academics, business leaders, First Nations and the Ministry’s own staff laid out a comprehensive plan back in 2008, and have been providing ongoing advice for years about the next steps we need to take,” said Andrew Weaver. “Now the government needs to show leadership by taking action – not by striking another expert panel to tell it what it already knows.”

Equally concerning is that while the government talks about it’s climate leadership, it has gutted its climate action initiatives to support its promises of an LNG industry. Such actions are a step backward for the province and are directly contrary to the goal of getting the province back on track to achieve our emissions reduction targets.

“While I welcome any effort to move forward on climate action, the Premier’s insistence that LNG form the centrepiece of the BC economy seriously damages our ability to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, as well as our credibility as a jurisdiction that is taking climate commitments seriously.”

If the Premier is serious about climate action, here are four actions she could take right now that would make a significant difference:

1. Re-start the annual increase of the carbon levy by $5 per tonne (up to a total of $50/tonne) and use the additional revenue generated from these further increases to help fund infrastructure and public transit investments that foster more sustainable communities, while reducing GHG emissions.

2. Update the BC building codes and infrastructure standards to allow for, and promote, the electrification of our vehicular fleet.

3. Reinstate the original Clean Energy Act. The purpose of the act was to require 93% of energy be produced from zero-emitting sources. It was changed in 2012 to deem natural gas a “clean” source of energy in order to accommodate the proposed LNG industry, despite the fact the burning natural gas releases GHG emissions.

4. Reinvigorate BC’s clean tech sector by having BC Hydro issue regular calls for power. Modify BC Hydro’s mandate to encourage the development of a geothermal capacity in BC. Reinstate the retail access program so that industry can partner with the cleantech sector to produce renewable energy for their use. Finally, BC Hydro’s mandate could further be modified to allow it to facilitate deals that would attract businesses who prioritize using renewable energy to BC, while ensuring that our base power can supply clean electricity for the increased demand we will face as a province.

-30-

Mat Wright

Press Secretary – Andrew Weaver MLA

Cell: 250 216 3382

Mat.wright@leg.bc.ca

Twitter: @MatVic

Parliament Buildings

Room 027C

Victoria BC V8V 1X4

Global BC1 Interview

Challenges Facing Mining in British Columbia

Introduction

Earlier this week I published an account of my recent trip to the Kootenays where I visited a number of mining operations, and met with people in local communities. Mining is a key economic sector underpinning BC’s economy. The industry directly employs 10,720 British Columbians, contributes $8.5 billion to BC’s GDP and a further $511 million in tax revenues to provincial coffers. Numerous small communities throughout our province depend on mining for their survival.

Earlier this week I published an account of my recent trip to the Kootenays where I visited a number of mining operations, and met with people in local communities. Mining is a key economic sector underpinning BC’s economy. The industry directly employs 10,720 British Columbians, contributes $8.5 billion to BC’s GDP and a further $511 million in tax revenues to provincial coffers. Numerous small communities throughout our province depend on mining for their survival.

While we have much to celebrate about British Columbia’s mining industry, there are also a number of challenges that must be taken seriously. The BC Government has a critical role to play in ensuring that the standards that regulate this industry are kept up to date, and that in addition to the economic benefits mining provides our province, its social and environmental impacts are being accounted for seriously.

To explore some of the challenges facing this industry – and to highlight some of the solutions that are readily available, I want to turn to two specific and related issues. First, I want to explore how mines manage their tailings ponds. I will specifically look at what we have learned since the Mount Polley tailings pond breach.

To explore some of the challenges facing this industry – and to highlight some of the solutions that are readily available, I want to turn to two specific and related issues. First, I want to explore how mines manage their tailings ponds. I will specifically look at what we have learned since the Mount Polley tailings pond breach.

The second issue I will examine concerns the enforcement and regulatory functions of government and whether adequate funding is being provided by government to ensure that it is managing the environmental and social consequences of mining operations.

Impacts of the Tsilhqot’in decision

Before diving into these issues, I think it is first important to acknowledge that for the mining industry in BC to continue to succeed, and do so in way that is environmentally and socially responsible, the BC government must ensure it is addressing the requirements placed on it by the Tsilhqot’in decision. We are already seeing examples of how this decision may affect mining investment. It was announced earlier this week that the BC Government bought back 61 coal licences from a mining company in the Northwest of the province, in order to provide a longer window for the BC government to engage in more meaningful government-to-government negotiations with the Tahltan First Nation.

Before diving into these issues, I think it is first important to acknowledge that for the mining industry in BC to continue to succeed, and do so in way that is environmentally and socially responsible, the BC government must ensure it is addressing the requirements placed on it by the Tsilhqot’in decision. We are already seeing examples of how this decision may affect mining investment. It was announced earlier this week that the BC Government bought back 61 coal licences from a mining company in the Northwest of the province, in order to provide a longer window for the BC government to engage in more meaningful government-to-government negotiations with the Tahltan First Nation.

Whether or not this specific policy tool — the re-purchasing of mining licences — becomes commonly used by the BC government, the status quo of mining development is likely to change. The Tsilhqot’in decision made it clear that First Nations have significant say, if not an outright veto, over developments on their land. Last summer the Tsilhqot’in First Nation established new rules for mining development on their titled land. These rules require companies to minimize negative impacts and provide revenue sharing with the community.

Mining companies who wish to develop new mines in British Columbia will need to put an even greater focus on consulting, and ultimately addressing the concerns of not only the BC Government, but First Nations who may have inherent title rights to the land.

Learning from Mount Polley

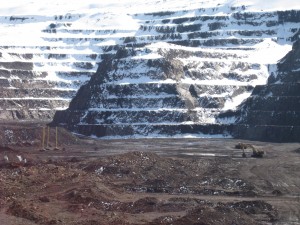

The mining industry in British Columbia was rocked last summer when the tailings pond at Mount Polley breached its impoundment dam, and released almost 25 million cubic meters of tailings and waste water into the Hazeltine Creek, and down into Quesnel Lake.

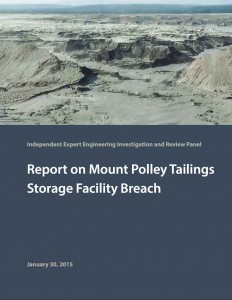

I wrote about this breach when it first happened, and after visiting the mine site and the surrounding communities, I explored in detail what had happened, and what some of the consequences were likely to be. Finally, in January of this year, the Independent Expert Engineering Investigation Review Panel published their report on the Mount Polley Breach. This Panel was empowered to investigate and report on the cause of the failure of the tailings pond facility that occurred on August 4th, 2014 at the Mount Polley Mine. In addition, they were asked to provide recommendations regarding how such an incident could be avoided in the future. It is these recommendations that I will focus on.

I wrote about this breach when it first happened, and after visiting the mine site and the surrounding communities, I explored in detail what had happened, and what some of the consequences were likely to be. Finally, in January of this year, the Independent Expert Engineering Investigation Review Panel published their report on the Mount Polley Breach. This Panel was empowered to investigate and report on the cause of the failure of the tailings pond facility that occurred on August 4th, 2014 at the Mount Polley Mine. In addition, they were asked to provide recommendations regarding how such an incident could be avoided in the future. It is these recommendations that I will focus on.

The Mount Polley tailings pond breach has shattered public confidence in government and industry ability to adequately protect the natural environment during mining operations. Regaining public trust and confidence is perhaps the greatest challenge facing the mining industry. First Nations, the Alaskan Government and Environmental groups have all raised similar concerns. How industry and government collectively respond to the Mount Polley breach will be critical in rebuilding this trust. And an ongoing examination of how mines are managing their tailings and waste, as well as a determination as to whether or not these reflect best practices, will almost certainly be one of key elements of moderating the concerns of British Columbians.

The Expert review panel touched on this point at the start of Section 9 of their report. Section 9 – entitled “Where Do We Go From Here” – explored how the BC mining industry can use best practices and best available technologies (BAT) to reduce failure rates to zero.

The Expert review panel touched on this point at the start of Section 9 of their report. Section 9 – entitled “Where Do We Go From Here” – explored how the BC mining industry can use best practices and best available technologies (BAT) to reduce failure rates to zero.

In the introduction to this section, the Panel rejected the concept of a “tolerable failure rate for tailings dams”, citing concerns that this would institutionalize failure. To quote from their report: “First Nations will not accept this, the public will not permit it, government will not allow it, and the mining industry will not survive it”.

A similar concern was voiced this week by Alaskan government, industry leaders and First Nations, who were in Victoria to meet with Minister’s regarding their concerns about the scale of development taking place in the British Columbia.

The tailings breach at Mount Polley was cited as having raised concerns about the potential impacts on the fishing industry in the region. The Alaskan delegation also felt that the review process in British Columbia was inadequate and not placing enough focus on potential cumulative impacts.

Interestingly both the Expert Review Panel and the group from Alaska pointed to the need to change the way that tailings are managed in this province.

The panel established three conditions that addressed the instability that is created when mines use dual-purpose impoundments, storing both water and tailings. Best available technology would dictate that where possible these two waste products need to be stored in separate facilities that are specifically designed to prevent tailings releases. Critically, this panel also noted that economic considerations cannot be allowed to be the dominant factor in determining what is feasible – the costs of another accident far outweigh the implementation of best practices and technology.

The panel established three conditions that addressed the instability that is created when mines use dual-purpose impoundments, storing both water and tailings. Best available technology would dictate that where possible these two waste products need to be stored in separate facilities that are specifically designed to prevent tailings releases. Critically, this panel also noted that economic considerations cannot be allowed to be the dominant factor in determining what is feasible – the costs of another accident far outweigh the implementation of best practices and technology.

Following the establishment of the Best-Available-Technology (BAT), the Expert Panel made the following recommendations:

- “For existing tailings impoundments: Constructing filtered tailings facilities on existing conventional impoundments poses several technical hurdles. Chief among them is undrained shear failure in the underlying saturated tailings, similar to what caused the Mount Polley incident. Attempting to retrofit existing conventional tailings impoundments is therefore not recommended, with reliance instead on best practices during their remaining active life.

- For new tailings facilities: BAT should be actively encouraged for new tailings facilities at existing and proposed mines. Safety attributes should be evaluated separately from economic considerations, and cost should not be the determining factor.

- For closure: BAT principles should be applied to closure of active impoundments so that they are progressively removed from the inventory by attrition. Where applicable, alternatives to water covers should be aggressively pursued.”

The BC Government has been somewhat responsive to this report. In mid-March they announced new interim rules for tailings ponds which would require companies seeking to build a mine in BC to include the best-available technologies for tailings facilities in their application. The Ministry of Mines are currently completing a review of mining regulations that will eventually establish the new way of doing business in BC.

The BC Government has been somewhat responsive to this report. In mid-March they announced new interim rules for tailings ponds which would require companies seeking to build a mine in BC to include the best-available technologies for tailings facilities in their application. The Ministry of Mines are currently completing a review of mining regulations that will eventually establish the new way of doing business in BC.

However in response to calls from Canadian and American groups to end the use of water based storage facilities, the Minister of Energy and Mines suggested that the expert panel’s bottom line is about reducing water storage of mine waste where you can, and reducing the risk by increasing safety factors. This statement, I fear, betrays a lack of commitment to the true underlying issue highlighted in the report – that the status quo cannot continue and that we must throw out any notion of acceptable risks. I share the frustrations of these groups that we have failed to see an open and transparent commitment to the recommendations of the Expert Report.

This process cannot be taken lightly by government. The Mount Polley breach was devastating to the community of Likely, and even today uncertainty exists as to the full extent of the environmental, social and economic costs that are faced by residents. Evidence of this uncertainty can be found in a recently research paper in Geophysical Research Letters that points to the possibility of ongoing and long-term environmental impacts from the spill on aquatic life. At the very least, long term monitoring of water and sediments in Quesnel Lake will be important.

The solutions are there — they are contained in the path forward highlighted by the Expert Panel. British Columbians deserve government to ensure that it establishes a truly credible mining regime in British Columbia, one which commands the confidence of all those who would feel its impacts. It is only under such a regime, where companies are responsible for the environmental and social impacts of their developments, that mining can be truly successful in our province.

This brings us to the second related issue facing this industry – Government’s ability to regulate and enforce the standards they set for the industry.

Professional Reliance

In 2001 after the BC Liberals were elected to their first term, they began a comprehensive core review to cut the size of government. Premier Campbell asked all government departments to prepare scenarios as to what it would look like with 20%, 35% and 50% cuts to spending. As a direct consequence of government downsizing, technical expertise within the civil service became a casualty. Instead of having technical expertise in house, the government moved towards wide scale use of Professional Reliance in the permitting process. Under the Professional Reliance approach, the Ministry relies on the judgment and expertise of qualified experts hired by a project proponent.

What is particularly important to note is that in March 2014, the Office of the British Columbia Ombudsperson released a scathing report criticizing the Professional Reliance model with respect to streamside protection and enhancement areas. The report, entitled The Challenges of Using a Professional Reliance in Environmental Protection – British Columbia’s Riparian Areas Regulation made 25 recommendations, 24 of which the government agreed to accept.

My own personal view is that the government’s approach to follow the Professional Reliance model is fraught with difficulties. The role of the government is to protect the public interest. When government is making decisions solely based on a project proponent’s expert opinion, it is very troubling. Imagine a judge in a court of law only listening to the expert opinion on one side of a case (plaintiff or defendant) and not allowing expert opinion to be submitted from the opposing side.

My own personal view is that the government’s approach to follow the Professional Reliance model is fraught with difficulties. The role of the government is to protect the public interest. When government is making decisions solely based on a project proponent’s expert opinion, it is very troubling. Imagine a judge in a court of law only listening to the expert opinion on one side of a case (plaintiff or defendant) and not allowing expert opinion to be submitted from the opposing side.

There is no doubt that mining plays a very important role in our economy. Mining provides us with the basic elements with which we have built British Colombia into a prosperous and successful jurisdiction. However, the mining industries’ importance to our economy does not disconnect it from its responsibility to conduct itself in a way the is both environmentally and socially responsible. The Expert Review panels report made it clear that the status quo is no longer acceptable and that change is needed. However, for industry to embrace this change, the BC government needs to step up to the plate. The lack of funding for the compliance and enforcement sections of our resource and environment ministries is putting us at risk of another accident. Furthermore, if we expect the mining industry to take the Expert Review panel’s recommendations seriously, we also need to be convinced that government takes them seriously as well.

Bill 23(46): A Multigenerational Sellout as a Final Act of Desperation

Today in the Legislature we discussed Bill 23, The Miscellaneous Statutes Amendment Act at the committee stage. As I noted earlier, the bill contained a profoundly troubling Section 46 which granted the Minister unparalleled powers to enter into secret deals with LNG companies concerning natural gas royalty rates. At second reading I outlined my concerns in detail. Bruce Ralston, NDP MLA from Surrey-Whalley, and I supported each other, including our amendments, as we unpacked the implications of this bill. Below is the text of some of my contributions. I also provide a link to the Hansard video for Part I.

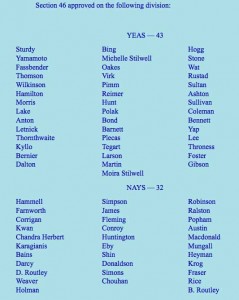

In the end both of my amendments as well as Bruce Ralston’s amendment were defeated. All members of opposition voted against section 46 as detailed below.

Video of Part I

Transcript of Part I

A. Weaver: Now, I recognize that government is rather desperate to land the $30 billion investment, and in so doing, we’re just seeing a $1 billion investment walk from Vancouver Island EDPR and TimberWest trying to put a billion-dollar wind farm investment…. Of course, government is not interested in that, because they’re desperate to fulfil this pipedream.

The concerns I have here…. I’ll ask a very direct one. In light of the fact that everything is up to the minister’s discretion, in essence, to enter into secret deals — presumably handed to him or her by a company, because this government has lost all credibility on this particular file — one of the things that they might do, for example, is work out a royalty rate that might actually be $1 billion less than it would otherwise be so that the company could then find a billion dollars to perhaps give to the First Nation to get title over their land. This is the kind of stuff that the public does not trust government on because of this legislation, where there’s nothing that precludes government working out a back deal to say: “Well done. Good for you to get your title rights recognized. Good for you to negotiate a cost. But we in the province of British Columbia will pay that cost, and we’ll pay that cost by changing this royalty rate in secrecy so that the company doesn’t actually pay it.” The province of British Columbia pays it.

My question to the minister is this, why does he need this level of secrecy, this level of secrecy here that he does not even need to give the Lieutenant-Governor-in-Council, his cabinet colleagues, notification as to what deals he is making? Does this minister honestly believe that the millions of people living in British Columbia trust him and only him to negotiate royalty rates for generations to come because somehow he knows what’s going on, and no one else does?

Hon. R. Coleman: I will walk past the ignorance of the question and just go to my answer. If the member would look and do some research with regards to the legislation, the power given to the minister to do this comes from Lieutenant-Governor-in-council, which is cabinet — the ability to do this. And if there’s any change in revenues or things that have to be adjusted on a financial basis, the minister, as I know, with regards to my service plan, my letters of expectations with my responsibility to government…. Anything that affects the government fiscally, I have to take back to Treasury Board.

I think it’s inappropriate for the member to think that it’s just the minister that’s making this decision. In addition to that, if the member would like to look at section 78.1, subsection (3), it also says that “The minister must, as soon as practicable, publish an agreement entered into under (1) but may withhold from publication anything in the agreement that could be refused to be disclosed under” — an act that governs us all — “the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act.” The only thing that would be not disclosed in that, I believe, would be if there was something that was significantly different or something that was — technology over whatever — with regards to the design of a plant or something that may have an effect on the competitive side or the marketplace before it was disclosed by the company in the appropriate manner.

If a request were made under that act, the disclosure of the agreement has to take place. It’s our full intent to make these agreements public.

A. Weaver: Well, in fact, I have read this legislation rather carefully. I’ve been following this file very carefully for the last two years. Frankly, what I’ve been saying for all that time is playing out here. Here’s another sellout.

In fact, if you read 78.1(2), it says the following: “The approval of the Lieutenant Governor in Council is not required for the minister to enter into an agreement under subsection (1)….” I don’t know what the minister doesn’t see about that, but it specifically says that “the Lieutenant Governor in Council is not required for the minister to enter into an agreement under subsection (1) (a) in the prescribed circumstances, or (b) in respect of a prescribed class of agreements.”

In essence, this is saying that the minister can essentially enter into an agreement…. The province of British Columbia, all of us, believe that we have such confidence in this minister that we are going to let him — and only him — go into an agreement with a multinational corporation. This has got to be some kind of a joke.

What is the justification that the minister needs these exclusive powers to go and enter into agreements without his cabinet colleagues knowing, without the Premier having to even know, but giving him power under section 78.1(2) to do this? What gives him the right? This is not an autocracy. Why does the minister think it is?

Hon. R. Coleman: If you read the section, it says: “in the prescribed circumstances, or (b) in respect of a prescribed class of agreements.” These are determined by Lieutenant-Governor-in-Council and allow the minister to sign them as a delegated authority to do so.

The characteristics of these agreements — in prescribed circumstances and in the class of agreements — are dealt with long before they’d ever get to an agreement with regards to what’s in them and what the minister can sign or cannot sign.

So basically, what it effectively does…. It does what most pieces of legislation do and delegates authority, after certain prescriptions and outlines have been prescribed by government, to a minister that he can execute on behalf of government.

Video of Part II

Transcript of Part II

A. Weaver: Coming back to section 46, section 78.1(2)(a) and (b) where it describes: “The approval of the Lieutenant Governor in Council is not required for the minister to enter into an agreement under subsection (1) (a) in the prescribed circumstances, or (b) in respect of a prescribed class of agreements.”

The minister recently said that the type of agreements that he or she or whoever the minister will be can enter into are controlled by cabinet. But we have no indication as to what “prescribed circumstances” are. We have no indication as to what “prescribed class of agreements” are.

It could be — and I seek confirmation from the minister — that a prescribed class of agreements could be any agreement to extract natural gas from the Montney region in British Columbia and export it anywhere in Asia. That’s one possible interpretation, and “under the prescribed circumstances,” that the minister has the time to do so. Essentially, this would grant the minister…. We have no sense of this.

Is what I just said precluded from that? What constraints are being placed on the minister to enter into these agreements without consulting, without the need for the Premier, without the need for cabinet, without the need for anyone, obviously, except the proponent to know about what the agreement is? This set of prescribed circumstances and agreements is so large and vague, it could include anything.

Hon. R. Coleman: It gives to the Lieutenant-Governor-in-Council, in prescribed circumstances or in respect of a prescribed class of agreements, to allow the minister to execute them. Those will be prescribed in regulation through Lieutenant-Governor-in-Council, not arbitrarily by the minister.

A. Weaver: I guess that’s my point. I reiterate what I said earlier. In light of the fact that this government is so desperate to sign agreements with now one company — it’s, I guess, given up on a number of others — there is a lack of trust. There’s a lack of trust that this section is not going to be anything more than “prescribed class of agreements” is with Petronus, for example, or with any company involved in the Montney play that wants to sell gas to Asia. So there is a great deal of uncertainty with this.

This amendment does simply not instill confidence in British Columbians that the government actually has any sense of direction or actual clue as to what they’re doing. They’re making it up as they go along, moving it from a generational to now, as my friend from Nanaimo–North Cowichan points out, a multigenerational sellout in a desperate attempt to try to land a company.

Let me just follow up with a direct question here. If the minister signs an agreement under subsection (2) and then after giving it to the Lieutenant-Governor-in-Council — now it’s signed — the Lieutenant-Governor-in-Council receive this, and they then determine that they don’t like it, that the minister overstepped his or her bounds, my question is: what ability does the Lieutenant-Governor-in-Council have to overturn an agreement that was signed by a minister under section 78.1(2)?

Hon. R. Coleman: I know that the NDP and the independents in this House don’t support liquefied natural gas as an industry for the future of the British Columbia. I know that. I know the member is clearly after that in his mind, and that’s fine.

But if the member will think about the legislation, it allows regulations to be developed that specify the circumstances or describe the types of agreements that the minister can enter into. Don’t get to write the agreements. The Lieutenant-Governor-in-Council actually prescribes that in regulation. And by the way, every week the decisions by the Lieutenant-Governor-in-Council on regulations are published. That information, in and around the agreements, would be published, and the minister could only execute under those terms. If he went outside those terms, because of the regulation being in place, it wouldn’t be a legally enforced agreement.

A. Weaver: With respect, this has nothing to do about being against or for natural gas. This has to do with economic folly and irresponsible promises by this government in an election campaign that they cannot fulfil. Here we see desperation in legislation. We see one after another as they so desperately try to land a single contract.

The reality is…. I’m going to read this again. I have read this legislation. It says as follows: “The approval of the Lieutenant Governor in Council is not required for the minister to enter into an agreement under subsection (1) (a) in the prescribed circumstances, or (b) in respect of a prescribed class of agreements.” It doesn’t say in respect to an agreement that has been reached and agreed to by cabinet already. It says in prescribed circumstances or a prescribed class of agreements, which is incredibly vague, no matter how you interpret that.

Again, to the minister. If he believes that these circumstances or agreements really curtail or constrain what he is able to sign, why doesn’t he tell us what they are? Why doesn’t he table here today what is actually meant by prescribed circumstances or a prescribed class of agreements? Right now it can be anything. Will the minister table examples of what these are?

Hon. R. Coleman: I’ll reiterate it. I do know the member opposite doesn’t support liquefied natural gas as a new industry for British Columbia. Even in that case, this is a piece of the legislation that allows for regulations to be developed that specify the circumstances that the minister could actually enter into and sign an agreement on behalf of the province of British Columbia.

The regulation is a law, hon. Member. The minister has to follow that law in those prescribed circumstances and in respect of the prescribed class of agreements. He has to do that, because that is defined in regulation. The regulation is developed when legislation is passed.

A. Weaver: Again, to correct the record, I have never said I am against liquefied natural gas. In fact, if you go back to estimates, you will see that I have been arguing strongly for promoting domestic sector use, including the use of liquefied natural gas in our ferry systems in British Columbia, long before the government actually came up with that direction and idea.

This is not about liquefied natural gas. This is about irresponsible economic outlook — that the government is going in with no financial underscoring. They seem to be the only ones in the world that believe this is going to play out, and they’re desperate to do so.

Coming back to the question. The reality is, as the minister would like us to believe, that somehow he’s going to be constrained in entering into these agreements, that the regulations will be developed after the fact.

There is no trust on this file anymore. So there is no trust. The government is simply not trusted to be acting in the best will of the people on this particular file. We’ve seen, time after time after time, broken promises, changing legislation. We bring in an act, an LNG act. We then completely change the LNG tax act only a few months later.

It’s for this reason that I have a second amendment that I wish to put here to actually add another check in place. This is on the order paper. It’s adding a section (8) to 78. So it’s 78.1(8), which says the following:

[SECTION 46, by adding the underlined text as shown:

(8) The Lieutenant Governor in Council may, without penalty, pull out of an agreement entered into under subsection (2) within six months of the time at which the minister provided the Lieutenant Governor in Council with the full text of the agreement.]

A. Weaver: The reason why I’m doing this is I don’t trust the minister. The opposition doesn’t trust the minister. The people of B.C. don’t trust the minister. International companies don’t trust the minister. The minister has no trust on this file.

Hon. R. Coleman: I guess he will have to understand what the law means with regards to regulation.

I should tell the member opposite that I spent eight years with the RCMP. You can’t throw an insult at me that’s going to bother me. So try as you must, it just isn’t going to work.

On the other side, the flip side, I know the member opposite doesn’t think that we have opportunities on liquefied natural gas in British Columbia. Like I said to him in debates of a while ago, I want to be invited to the dinner when he has to eat those words. It will happen in the not too distant future, I believe.

Over the next year or two, you’ll see a number of these projects go ahead. They’ll go ahead not because the international community mistrusts the minister. It’s because the minister has built a relationship with the industry across the world and with financiers to the fact that they actually believe this government will deliver on what it says it will do and, therefore, will come to B.C. and invest.

The Vote

Interview on BC1

Celebrating Mining Week in British Columbia

This week we celebrate mining in British Columbia. From May 3-9 events will be held across British Columbia to highlight the importance of mining to British Columbians.

B.C.’s mining industry is one of the pillars of our economy. In 2013, the year for which most recent data is available, the mining sector contributed $8.5 billion to BC’s GDP and employed 10,720 British Columbians. It further contributed $511 million in tax revenues to provincial coffers. Mining forms the backbone of many rural communities throughout the province, supplying us with the resources we need to enjoy the prosperity we are so fortunate to have in B.C.

Our mining industry continues to play a pivotal role in facilitating the transition to a 21st century economy. For example, without metallurgical coal, we cannot manufacture steel. Without graphite, we cannot build lithium ion batteries.

It is for this reason that I travelled to the Kootenays in April to learn more about the opportunities and challenges facing our Mining Industry in B.C. What follows is a brief report on two tours I did while I was there.

Teck Resources Ltd Metallurgical Coal Operations

Employing roughly 7,960 people and contributing $6.5 billion in gross mining revenue, Teck Resources Ltd is Canada’s largest diversified resource company, with many of its assets in metallurgical coal mining. I reached out to Teck Resources because I believe it’s important to have a clear understanding of British Columbia’s coal industry.

Employing roughly 7,960 people and contributing $6.5 billion in gross mining revenue, Teck Resources Ltd is Canada’s largest diversified resource company, with many of its assets in metallurgical coal mining. I reached out to Teck Resources because I believe it’s important to have a clear understanding of British Columbia’s coal industry.

Five of Teck Resources’ thirteen mines are located in the Elk Valley in the Kootenays where they extract metallurgical coal. While I was there, I had the opportunity to meet with representatives from Teck Resources and to tour their Coal Mountain operations.

Those who have read my previous coal-related posts know how important I believe it is to distinguish between thermal coal, which is used for coal-fired power plants, and metallurgical coal, which is used in the production of steel. Metallurgical coal is used to produce coke. This is done via heating the coal to very high temperatures (>1000°C) in the absence of oxygen. The resulting almost pure carbon is then mixed with iron ore to create the molten iron that is turned into steel.

Thermal coal, on the other hand, is the single biggest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions in the world. It is also the most widely available of all fossil fuels and we produce very little of it here in British Columbia. Thermal coal has smaller carbon content and higher moisture content that metallurgical coal thereby precluding its use in steel making.

Thermal coal, on the other hand, is the single biggest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions in the world. It is also the most widely available of all fossil fuels and we produce very little of it here in British Columbia. Thermal coal has smaller carbon content and higher moisture content that metallurgical coal thereby precluding its use in steel making.

The overwhelming majority of thermal coal that is shipped through British Columbia ports is sourced from the United States. That coal travels through B.C. ports because Washington, Oregon, and California have taken a stand to curb their own thermal coal exports. To quote from the governors of Oregon and Washington “We cannot seriously take the position in international and national policymaking that we are a leader in controlling greenhouse gas emissions without also examining how we will use and price the world’s largest proven coal reserves.” Here they were acknowledging that the United States has the largest reserves of thermal coal in the world (237,295 million tonnes) and that their domestic market is dropping as natural gas generation increases and more renewables are brought on stream.

Teck Resources produces metallurgical (not thermal) coal here in British Columbia. The fact is that metallurgical coal is essential for building everything from windmills to electric cars because without it, you cannot have steel. Teck Resources’ five metallurgical coal mines in the Elk Valley employ about 4,000 people and together contributed $140 million in taxes to the province in 2014. Touring Teck Resources’ Coal Mountain mining operation offered an excellent view into the scale and complexities of modern metallurgical coal mining in British Columbia. I was extremely impressed by steps Teck has taken to ensure their metallurgical coal operations were as environmentally sensitive as possible. These include their approaches to reclamation, greenhouse gas reductions, acquisition and preservation of parkland for future generations, and their state of the art water treatment operations that will commence in the Fall of this year.

Teck Resources produces metallurgical (not thermal) coal here in British Columbia. The fact is that metallurgical coal is essential for building everything from windmills to electric cars because without it, you cannot have steel. Teck Resources’ five metallurgical coal mines in the Elk Valley employ about 4,000 people and together contributed $140 million in taxes to the province in 2014. Touring Teck Resources’ Coal Mountain mining operation offered an excellent view into the scale and complexities of modern metallurgical coal mining in British Columbia. I was extremely impressed by steps Teck has taken to ensure their metallurgical coal operations were as environmentally sensitive as possible. These include their approaches to reclamation, greenhouse gas reductions, acquisition and preservation of parkland for future generations, and their state of the art water treatment operations that will commence in the Fall of this year.

Now, Teck Resources does not only produce metallurgical coal. They also own and operate Highland Valley Copper and the integrated zinc and lead smelting facility in Trail. If we actually include all of Teck Resources’ operations in our province, this one company accounted for 21% of all BC exports to China in 2013. That year Resources directly employed 7,650 full-time workers with an average salary of $100,000 per year. They are expanding their operations in British Columbia and presently there are 28 job openings within the company.

Eagle Graphite

Whereas Teck Resources is British Columbia’s largest mining company, many of B.C.’s junior mining companies are quite a bit smaller. Eagle Graphite Mine is one of them.

Whereas Teck Resources is British Columbia’s largest mining company, many of B.C.’s junior mining companies are quite a bit smaller. Eagle Graphite Mine is one of them.

Located in the Slocan Valley, Eagle Graphite is one of only two flake graphite producers in North America and the only one in British Columbia. Graphite is an essential component of lithium ion batteries, which are used in electric vehicles. In fact, about 95% of a lithium battery is made up of graphite. About 50 kilograms of graphite is contained in an electric car, 10 kilograms in a hybrid vehicle and 1 kg in an electric bike. Laptops and mobile phones contain about 100 grams and 15 grams, respectively.

Located in the Slocan Valley, Eagle Graphite is one of only two flake graphite producers in North America and the only one in British Columbia. Graphite is an essential component of lithium ion batteries, which are used in electric vehicles. In fact, about 95% of a lithium battery is made up of graphite. About 50 kilograms of graphite is contained in an electric car, 10 kilograms in a hybrid vehicle and 1 kg in an electric bike. Laptops and mobile phones contain about 100 grams and 15 grams, respectively.

By the end of the decade, graphite demand for electric vehicles produced in North America is projected to increase substantially, far exceeding current supply. The team at Eagle Graphite has been working hard to take advantage of this projected supply gap by proving their reserves and developing methods to efficiently extract graphite from their quarry reserves. And one of the interesting tidbits I picked up on the tour was that golf course grade sand is the by-product of producing graphite!

Touring Eagle Graphite offered a helpful insight into the opportunities and challenges faced by smaller mining firms.

Summary

My brief trip to the Kootenays highlighted the diversity of resource opportunities that have been capitalized upon in the area. What impressed me most at the locations I visited were the steps taken by all companies involved to ensure sustainability of their industry for decades to come with minimal environmental footprint. Whether it be Teck Resource’s Elk Valley coal operations or their Trail smelter powered by the Waneta Dam, Eagle Graphite’s small operation, Canfor’s Elko Mill, or Columbia Power’s Waneta Expansion Project, everyone I met was beaming with pride at the work that they do, their safety records, and the care they take to ensure their operations are as clean and sustainable as possible. After all, these people are locals and the industrial operations are literally in their backyard.

Finally, a highlight of my trip truly had to be that I can now say triumphantly “I’ve been to Yahk and Back”.

NEB Denies My Motion for More Adequate Answers

For more than a year now, I have been trying to get Trans Mountain to answer my questions on their pipeline proposal. As an intervenor in the National Energy Board (NEB) hearings, getting answers to questions is an essential prerequisite to offering an informed argument on whether the pipeline should be built or not.

Sadly, today I learned that the NEB has fully denied my second and final opportunity to get answers to essential questions. What is even more troubling is that I’m not alone.

Collectively, intervenors challenged 1,291 of the roughly 5,700 questions posed to Trans Mountain during the second round of information requests. Of those 1,291 questions, the National Energy Board only ruled in intervenors’ favour 32 times. Put another way, the NEB ruled in Trans Mountain’s favour 97.6% of the time.

Personally, I submitted nearly 100 questions this round and challenged 24 of the answers I received.

To be clear, I was not challenging unsatisfactory answers, or answers I disagreed with. There were many cases where I disagreed with the response that was given, but still received an answer.

Instead, I was challenging answers that simply did not respond to my questions.

Here’s an example:

One of my biggest concerns is that, from the information I have seen, we currently have no capacity to recover sunken or submerged oil. That means that if an oil spill were to occur, and the oil were to sink, we would have no way to clean it up.

For me, this is the line in the sand. We should not be transporting heavy oils along our coast if we cannot clean them up when they sink.

I therefore asked Trans Mountain to provide a list of all equipment owned and operated by Western Canada Marine Response Corporation (WCMRC – the organization that is contracted to respond to oil spills along the B.C. coast) that can be used to recover sunken oil.

In response, Trans Mountain acknowledged that heavy oils can sink under certain circumstances, but failed to provide the requested list. I noted this when I challenged the response, and asked that Trans Mountain provide the requested list. Once again, they did not.

After a back-and-forth, the NEB then gave the following ruling:

Deny – Motion sought information that Trans Mountain is not responsible for, or which is the responsibility of another body (e.g., regulator, tanker operators).

Deny – Motion sought information that may touch upon the List of Issues, but would not contribute to the record in any substantive way and, therefore, would not be material to the Board’s assessment. In some instances, the request was unreasonable or overly broad in scope.

How the NEB can feel that a basic question about WCMRC’s capacity to respond to sunken oil “would not contribute to the record in any substantive way” is beyond me. In my mind, that is one of the most fundamental questions to the whole hearing process. Can we clean up a heavy oil spill? And if we don’t know what equipment WCMRC has, how can we know if we can clean up a spill?

But here’s the other problem:

The NEB has ruled that Trans Mountain isn’t responsible for providing information on behalf of WCMRC. Yet, WCMRC isn’t directly involved in the hearing process. So we have a situation where we cannot get the information on record from Trans Mountain, but we also cannot get the information on record from WCMRC within the formal hearing process.[1]

This brings me back to the essential question: How can the NEB truly evaluate Trans Mountain’s ability to respond to a spill when they seem to have created a situation that denies the Board, and intervenors, the ability to get the information we need?

[1] It should be noted that WCMRC did take the time to meet with my staff and were incredibly helpful. They spent several hours going through their oil spill response plan and answering our questions. However, since that meeting occurred outside the parameters of the hearing process, the information they provided is not necessarily on record within the formal hearings and therefore cannot be considered by the National Energy Board.