Environment

The ‘Gulf Stream’ will not collapse in 2025: What the alarmist headlines got wrong

Today I published an article in The Conversation concerning the headlines last week proclaiming the Gulf Stream could collapse as early as 2025. Facebook has decided to block reposting of news stories originating from Canada on their site, so I decided to reproduce the article here. Please go to the link above for the published online version.

Published Article

Those following the latest developments in climate science would have been stunned by the jaw-dropping headlines last week proclaiming the “Gulf Stream could collapse as early as 2025, study suggests” — which responded to a recent publication in Nature Communications.

“Be very worried: Gulf Stream collapse could spark global chaos by 2025” announced the New York Post. “A crucial system of ocean currents is heading for a collapse that ‘would affect every person on the planet” noted CNN in the U.S. and repeated CTV News here in Canada.

“Be very worried: Gulf Stream collapse could spark global chaos by 2025” announced the New York Post. “A crucial system of ocean currents is heading for a collapse that ‘would affect every person on the planet” noted CNN in the U.S. and repeated CTV News here in Canada.

One can only imagine how those already stricken with climate anxiety internalized this seemingly apocalyptic news as temperature records were being shattered across the globe.

This latest alarmist rhetoric provides a textbook example of how not to communicate climate science. These headlines do nothing to raise public awareness, let alone influence public policy to support climate solutions.

We see the world we describe

It is well known that climate anxiety is fuelled by media messaging about the looming climate crisis. This is causing many to simply shut down and give up — believing we are all doomed and there is nothing anyone can do about it.

Alarmist media framing of impending doom has become quintessential fuel for personal climate anxiety, and when amplified by sensational media messaging, it is quickly emerging as a dominant factor in the collective zeitgeist of our age, the Anthropocene.

This is also not the first time such headlines have emerged. Back in 1998, the Atlantic Monthly published an article raising the alarm that global “warming could lead, paradoxically, to drastic cooling — a catastrophe that could threaten the survival of civilization.”

In 2002, editorials in the New York Times and Discover magazine offered the prediction of a forthcoming collapse of deep water formation in the North Atlantic, which would lead to the next ice age.

Building on the unfounded assertions in these earlier stories, BBC Horizon televised a 2003 documentary entitled The Big Chill, and in 2004 Fortune magazine published “The Pentagon’s Weather Nightmare,” piling on where previous articles left off.

Seeing the opportunity for an exciting disaster movie, Hollywood stepped up to created The Day After Tomorrow in which every known law of thermodynamics was ever so creatively violated.

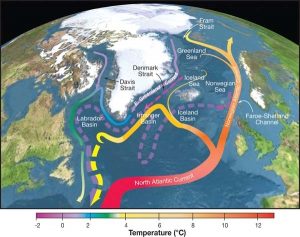

The currents are not collapsing (anytime soon)

While it was relatively easy to show that it is not possible for global warming to cause an ice age, this still hasn’t stopped some from promoting this false narrative.

The latest series of alarmist headlines may not have fixated on an impending ice age, but they still suggest the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation could collapse by 2025. This is an outrageous claim at best and a completely irresponsible pronouncement at worst.

The latest series of alarmist headlines may not have fixated on an impending ice age, but they still suggest the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation could collapse by 2025. This is an outrageous claim at best and a completely irresponsible pronouncement at worst.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has been assessing the likelihood of a cessation of deep-water formation in the North Atlantic for decades. In fact, I was on the writing team of the 2007 4th Assessment Report where we concluded that:

“It is very likely that the Atlantic Ocean Meridional Overturning Circulation (MOC) will slow down during the course of the 21st century. It is very unlikely that the MOC will undergo a large abrupt transition during the course of the 21st century.”

Almost identical statements were included in the 5th Assessment Report in 2013 and the 6th Assessment Report in 2021. Other assessments, including the National Academy of Sciences Abrupt Impacts of Climate Change: Anticipating Surprises, published in 2013, also reached similar conclusions.

The 6th assessment report went further to conclude that:

“There is no observational evidence of a trend in the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), based on the decade-long record of the complete AMOC and longer records of individual AMOC components.”

Understanding climate optimism

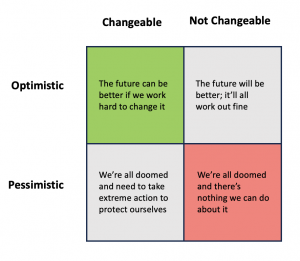

Hannah Ritchie, the deputy editor and lead researcher at Our World in Data and a senior researcher at the Oxford Martin School, recently penned an article for Vox where she proposed an elegant framework for how people see the world and their ability to facilitate change.

Ritchie’s framework lumped people into four general categories based on combinations of those who are optimistic and those who are pessimistic about the future, as well as those who believe and those who don’t believe that we have agency to shape the future based on today’s decisions and actions.

Ritchie’s framework lumped people into four general categories based on combinations of those who are optimistic and those who are pessimistic about the future, as well as those who believe and those who don’t believe that we have agency to shape the future based on today’s decisions and actions.

Ritchie persuasively argued that more people located in the green “optimistic and changeable” box are what is needed to advance climate solutions. Those positioned elsewhere are not effective in advancing such solutions.

More importantly, rather than instilling a sense of optimism that global warming is a solvable problem, the extreme behaviour (fear mongering or civil disobedience) of the “pessimistic changeable” group (such as many within the Extinction Rebellion movement), often does nothing more than drive the public towards the “pessimistic not changeable” group.

A responsibility to communicate, responsibly

Unfortunately, extremely low probability, and often poorly understood tipping point scenarios, often end up being misinterpreted as likely and imminent climate events.

In many cases, the nuances of scientific uncertainty, particularly around the differences between hypothesis posing and hypothesis testing, are lost on the lay reader when a study goes viral across social media. This is only amplified in situations where scientists make statements where creative licence is taken with speculative possibilities. Possibilities that reader-starved journalists are only too happy to play up in clickbait headlines.

Through independent research and the writing of IPCC reports, the climate science community operates from a position of privilege in the public discourse of climate change science, its impacts and solutions.

Climate scientists have agency in the advancement of climate solutions, and with that agency comes a responsibility to avoid sensationalism. By not tempering their speech, they risk further ratcheting up the rhetoric with nothing to offer in terms of overall solutions or risk reduction.

Temperature records shattered across the world as tourists flock to experience the heat

Yesterday I published an article in The Conversation. It is reproduced below as Facebook appears to be blocking reposting of Canadian news articles.

The Article

This June was the warmest one ever recorded and unprecedented summer heat waves are now gripping southern Europe, China, the Middle East and the southern United States.

In the face of such unprecedented heat, one would think that the world would wake up to the urgent need to rapidly decarbonize energy systems, transition to a low carbon economy and increase investment in negative emission technologies.

California’s Death Valley recorded 56.6 C temperatures, and rather than reflecting on the obvious effects of global warming, tourists flocked to the area. Similarly, thrill-seeking visitors rushed to Xinjiang, China, to experience 80 C surface temperatures and more than 50 C air temperatures.

Tourists also headed in droves to the beaches and historical sites of Italy, Spain and Greece, where governments were warning them to stay indoors to avoid the potentially life-threatening heat.

In Canada, we have already experienced our worst recorded forest fire season. And in British Columbia, where I live, we have already broken the previous 2018 record with more than 13,900 square kilometres burnt. And this is just the beginning of the 2023 fire season.

Remarkable cognitive dissonance

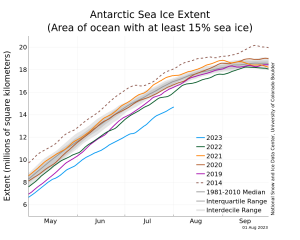

I doubt those jetting off to visit the heat-ravaged regions of the world are aware that Antarctica has already shattered previous sea ice melt records, with potentially dire consequences for glacial outflow and future sea level rise.

I doubt those jetting off to visit the heat-ravaged regions of the world are aware that Antarctica has already shattered previous sea ice melt records, with potentially dire consequences for glacial outflow and future sea level rise.

Are tourists aware that coral reefs worldwide are in the process of dying off on an unprecedented scale?

Perhaps they might want to reflect on the fact that Earth has already warmed by around 1.1 to 1.2 C since pre-industrial times.

Many may not realize that even if worldwide fossil fuel combustion was immediately eliminated, the roughly 0.5 C cooling contribution of atmospheric aerosols — also the result of existing fossil fuel combustion — would rapidly dissipate through gravitational settling and precipitation scavenging of these aerosols. This would cause the Earth to warm rapidly to around 1.6 to 1.7 C above pre-industrial levels.

The warming does not end there, as the planet is on course to go well above 2 C in the decades ahead once reduced aerosol cooling, permafrost melt and other greenhouse gases are taken into account.

I suspect that these travellers are unaware that when these other pesky greenhouse gases are included, the net radiative effect is equivalent to 523 ppm CO2e, of which only 417 ppm is from CO2 alone.

The Paris Agreement

Governments worldwide have signed on to the 2015 Paris Agreement committing nations to collectively limit global warming to well below 2 C above pre-industrial levels while pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 C.

The Paris Agreement might appear promising. But the reality is that the 1.5 C guardrail cannot be met, and that socioeconomic inertia prevents us from even staying below the 2 C threshold. Even if every country met its promised emissions reductions, global mean temperatures would still soar past 2 C.

We have known for more than 15 years that “if a 2.0 C warming is to be avoided, direct CO2 capture from the air, together with subsequent sequestration, would eventually have to be introduced in addition to sustained 90 per cent global carbon emissions reductions by 2050.”

So, while governments, industry and public sector institutions worldwide are announcing their intention to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, the reality is these are nothing more than aspirational goals made by decision-makers who will not be around to be held accountable for the decisions they made.

Reaching net-zero

To meet the target of these net-zero claims, most will rely on so-called nature-based solutions such as planting trees, using biochar in soils to enhance soil carbon uptake and restoring mangroves, salt marshes and seagrass meadows.

To be clear, nature-based climate solutions have an important role to play.

Human disruption of natural ecosystems has accounted for about 30 per cent of historical greenhouse gas emissions, so it is reasonable to expect nature-based climate solutions to have a key role to play moving forward.

But there are limits, not the least of which is that global warming will continue to cause increased wildfires in the years ahead. And these wildfires release the carbon stored in the vegetation back to the atmosphere.

While nature-based solutions can help in climate change adaptation and the preservation of biodiversity, there is a growing danger that governments, industry and the public will come to rely on them to maintain the status quo, thereby delaying what is actually needed.

We now need an immediate transition towards the decarbonization of global energy systems and the widespread introduction of negative emission technology, such as direct air carbon capture and deep underground carbon sequestration.

We now need an immediate transition towards the decarbonization of global energy systems and the widespread introduction of negative emission technology, such as direct air carbon capture and deep underground carbon sequestration.

This is the only hope humanity has for a long-term solution to global warming.

We can take comfort in the very real successes of nature-based solutions and their many benefits. But we cannot take our eyes off the scale of the challenge before us. While all the solutions are known, achieving the goals of net zero emissions in the future is a matter of individual, institutional, corporate and political will.

Rather than jetting off around the world to feel the heat, perhaps it’s time for everyone to take a good hard look at their individual contribution to global warming.

Each of us is part of the problem, meaning that each of us can also be part of the solution. And this notion can create an environment ripe for innovation and creativity — the foundational requirements of any prosperous and vibrant future.

Advancing nature based climate solutions: a cautionary tale

In recent years, governments and industry have become more and more interested in supporting so-called nature based climate solutions. So what are such solutions? The Nature Conservancy provides a concise definition: Nature-based climate solutions “are actions to protect, better manage and restore nature to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and store carbon.”

Such solutions aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions (mitigation) fall into two categories: 1) those that the enhance the uptake and storage of carbon within natural ecosystem; 2) those that reduce the emissions of greenhouse gases (e.g., carbon dioxide and methane) from natural ecosystems.

While the above definition recognizes the link between natural ecosystems and the global carbon cycle, nature based solutions also play a critical role in climate change adaptation strategies. A more complete definition that includes both their roles has been offered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and subsequently used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

“Nature-based Solutions are actions to protect, sustainably manage, and restore natural and modified ecosystems that address societal challenges effectively and adaptively, simultaneously benefiting people and nature.“

Below I attempt to highlight the important role that such solutions play in both climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies. But I try to put such solutions in the bigger context of what needs to be done to meet the challenge of global warming. I’ll attempt to outline why governments and industry appear to be so supportive of such solutions, yet point out the danger of over-relying on them.

To be clear, nature-based climate solutions have a crucial role to play. Cumulative anthropogenic fossil carbon emissions from 1750 to 2021 have been 474 GtC (billions of tons of carbon), while deforestation and land use changes have contributed another 203 GtC. That is, anthropogenic disruption of natural ecosystems has accounted for about 30% of historical greenhouse gas emissions, so it seems reasonable to expect nature-based climate solutions to have an important role to play moving forward. But there are limits. In fact, a recent paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggested that nature-based solutions could be used to meet 20% of the required emission reductions to be implemented prior to 2050 to keep global warming to below 2°C. I’ve pointed out for years (and summarized these views again recently), that the 1.5°C target was not attainable even when proposed in the 2015 Paris Accord, due to socioeconomic inertia in our built environment, the role of atmospheric aerosols, and potential effects from the permafrost carbon feedback.

Examples of Nature Based Climate Solutions

To start, I thought it would be illustrative to provide a few examples of nature based climate solutions in action. This list is by no means comprehensive, but rather serves solely to give the reader a sense of what such solutions entail.

The most obvious example of a nature based solution is planting trees. Widespread deforestation, particularly in the creation of pastures for cattle grazing and land for farming or other human uses, has provided the lion’s share of the historical 203 GtC released to the atmosphere. Reforestation (planting trees where they once were) and afforestation (planting trees in places where they weren’t historically present) both have the potential to draw carbon from they atmosphere as they grow. But of course, if we want to use tree planting in carbon budget accounting, we would also have keep track of the carbon released during forest fires.

The most obvious example of a nature based solution is planting trees. Widespread deforestation, particularly in the creation of pastures for cattle grazing and land for farming or other human uses, has provided the lion’s share of the historical 203 GtC released to the atmosphere. Reforestation (planting trees where they once were) and afforestation (planting trees in places where they weren’t historically present) both have the potential to draw carbon from they atmosphere as they grow. But of course, if we want to use tree planting in carbon budget accounting, we would also have keep track of the carbon released during forest fires.

Urban planners also incorporate tree management in their climate adaptation strategies. For example, they recognize that increasing the tree canopy can help keep cities cooler in the summer than they would otherwise be. Homeowners, for example, might plant deciduous trees in their front yard that blocks the sun from their main windows in the summer, but allow the sunshine in during the late fall and winter once the leaves have fallen.

The use of biochar to enhance the properties of soil has also been proposed as a potential nature-based climate solution. Biochar (a charcoal like substance) is created through a process known as biomass pyrolysis. (high temperature decomposition of plant material). The addition of biochar to agricultural soil leads to enhanced soil carbon uptake and storage, reduced requirement for fertilizer use (and hence reduced nitrous oxide emissions), and improved water use efficiency. Other agricultural nature-based solutions involving tiling practices, crop/grazing rotations, cover crops etc. have also been proposed.

The use of biochar to enhance the properties of soil has also been proposed as a potential nature-based climate solution. Biochar (a charcoal like substance) is created through a process known as biomass pyrolysis. (high temperature decomposition of plant material). The addition of biochar to agricultural soil leads to enhanced soil carbon uptake and storage, reduced requirement for fertilizer use (and hence reduced nitrous oxide emissions), and improved water use efficiency. Other agricultural nature-based solutions involving tiling practices, crop/grazing rotations, cover crops etc. have also been proposed.

In the coastal ocean, mangroves, salt marshes and seagrass meadows more efficiently capture and store carbon than land based, slow-growing forests. Many of these so called “blue carbon” sinks have been stressed by human activity in research decades and steps have been taken to both preserve and enhance their health and extent. These rich, biodiverse ecosystems also play key roles in climate change adaptation as they serve to protect coastal erosion from storms and sea level rise.

In the coastal ocean, mangroves, salt marshes and seagrass meadows more efficiently capture and store carbon than land based, slow-growing forests. Many of these so called “blue carbon” sinks have been stressed by human activity in research decades and steps have been taken to both preserve and enhance their health and extent. These rich, biodiverse ecosystems also play key roles in climate change adaptation as they serve to protect coastal erosion from storms and sea level rise.

Recognizing the importance of nature-based solutions, the Canadian federal government developed a natural climate solutions fund to protect, enhance and preserves Canada’s biodiverse and carbon rich wetlands, grasslands and forests, in addition to a commitment to plant two billion trees over a ten-year period.

What’s required to stabilize atmospheric temperature

As most everyone is aware, the goal of the internationally-negotiated Paris Agreement is to limit global warming to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels while pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C. Yet we’ve known for more than 15 years that such a target would ultimately require rapid decarbonization and the introduction and scale-up of negative emission technology. In a paper entitled Long term climate implications of 2050 reduction targets that we published in 2007, we note in the abstract (and discussed below):

“Our results suggest that if a 2.0°C warming is to be avoided, direct CO2 capture from the air, together with subsequent sequestration, would eventually have to be introduced in addition to sustained 90% global carbon emissions reductions by 2050.“

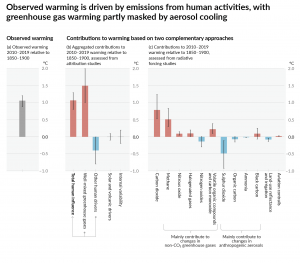

Earth has already warmed by ~1.1-1.2 °C since preindustrial times and if worldwide fossil fuel combustion was immediately eliminated, the direct and indirect net cooling effect of atmospheric aerosol loading would rapidly dissipate through gravitational settling and precipitation scavenging of these aerosols. As such, the source of the ~0.5 °C aerosol cooling realized since the preindustrial era would be eliminated (see Figure 1), thereby taking the Earth rapidly to ~1.6-1.7 °C warming. The Earth would warm further as we equilibrate to the present 523 ppm CO2e (NOAA 2023) greenhouse gas loading in the atmosphere (only 417 ppm of which is associated with CO2), and that is not including the committed warming from the permafrost carbon feedback that would add another 0.1 to 0.2 °C this century (Macdougall et al, 2013).

Figure 1: Observed global warming (2010-2019 relative to 1850-1900) and the contribution to this net warming by observed changes to natural and anthropogenic radiative forcing. Reproduced from IPCC (2021).

Let’s once more explore the level of decarbonization required to keep warming below 2°C (recognizing that 1.5°C is no longer attainable). I present results from the UVic Earth System Climate model discussed in Weaver et al. (2007) and my book Keeping our Cool: Canada in a Warming World.

Starting from a pre-industrial equilibrium climate, I force the UVic model with observed natural and human-caused radiative forcing until the end of 2005. After 2005, future trajectories in emissions must be specified. Each of the post-2005 scenarios I use assumes that contributions to radiative forcing from sulphate aerosols and greenhouse gases other than carbon dioxide remained fixed throughout the simulations. An alternative way of looking at this is that any increase in human- produced, non-carbon dioxide greenhouse gases is assumed to be balanced by an increase in sulphate aerosols (or some other negative radiative forcing). This assumption should be viewed as extremely conservative, since most future emissions scenarios have decreasing sulphate emissions and increasing emissions of non-carbon dioxide greenhouse gases.

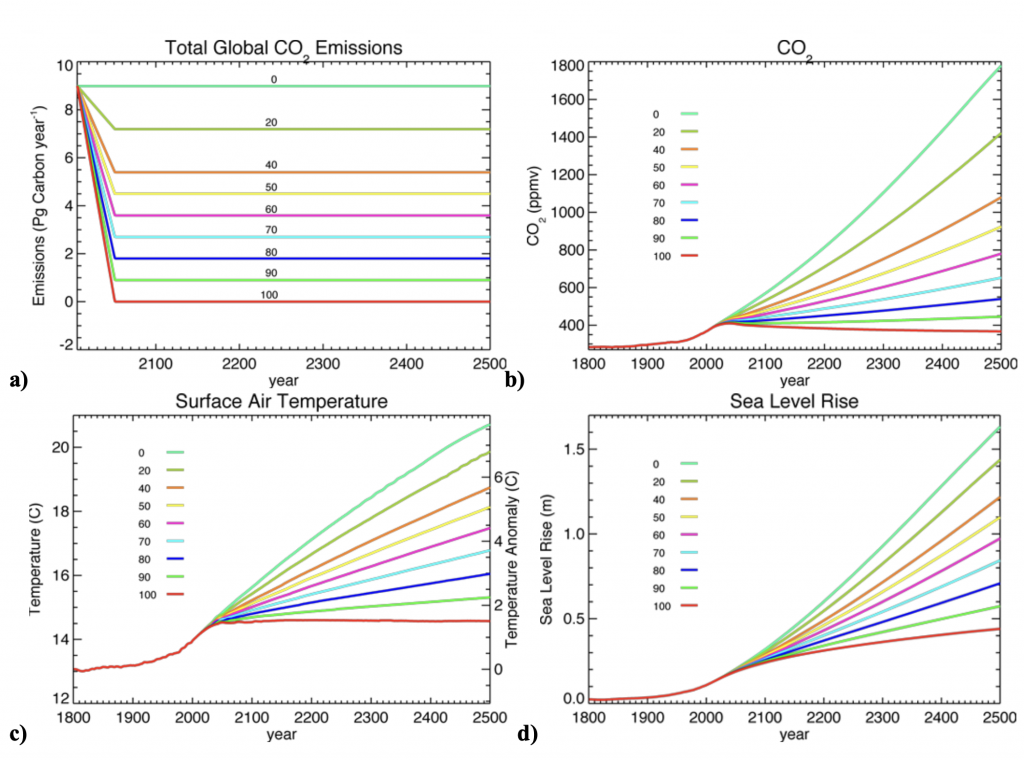

We’ll start by examining the effects of a hypothetical international policy option that linearly cuts emissions by some percentage of 2006 levels by 2050, and maintains emissions constant thereafter until the year 2500 (see Figure 2a). Of course, my baseline case of constant 2006 emissions is substantially more optimistic than the IPCC scenarios, some of which have 2050 emissions at more than double 2006 levels. The various pathways in emissions lead to atmospheric carbon dioxide levels in 2050 ranging from 407 ppm to 466 ppm, corresponding to warming relative to 1800 of between 1.5°C and 1.8°C (Figure 2b and Figure 2c). As the twenty-first century progresses, the atmospheric carbon dioxide levels and warming begin to diverge between scenarios, and by 2100 the range is 394 ppm to 570 ppm (we are presently at 417 ppm), with a warming of between 1.5°C and 2.6°C. None of the emissions trajectories lead to an equilibrium climate and carbon cycle in 2500, although the 90% and 100% sustained 2050 emissions reductions have atmospheric carbon dioxide levels that are levelling off. Of particular note is that by 2500, the scenario depicting a 100% reduction in emissions leads to an atmospheric carbon dioxide level below that in 2006, although global mean surface air temperature is still 0.5°C warmer than in 2006 (1.5°C warmer than 1800). While this version of the UVic Earth System Model only calculates the thermal expansion component of seal level rise and ignores contributions from glacier and ice sheet melt, the results shown in Figure 2d indicate that sea level rise still has not equilibrated even after 500 years.  Figure 2: (a) Observed anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions from 1800 to 2006 (red) followed by linear reductions of 0–100% of 2006 levels by 2050. From 2050 onwards emissions are held constant. Transient evolution of globally-averaged (b) atmospheric carbon dioxide, (c) surface air temperature, and (d) sea level rise due to thermal expansion for all experiments. Note that the sea-level curves have no contribution from the melting of land-based ice.

Figure 2: (a) Observed anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions from 1800 to 2006 (red) followed by linear reductions of 0–100% of 2006 levels by 2050. From 2050 onwards emissions are held constant. Transient evolution of globally-averaged (b) atmospheric carbon dioxide, (c) surface air temperature, and (d) sea level rise due to thermal expansion for all experiments. Note that the sea-level curves have no contribution from the melting of land-based ice.

All simulations that have less than a 60% reduction in global emissions by 2050 eventually break the threshold of 2°C warming this century. Even if emissions are eventually stabilized at 90% less than 2006 levels globally (1.1 billions of tonnes of carbon emitted per year), the 2°C threshold warming limit is eventually broken well before the year 2500. This implies that if a 2°C warming is to be avoided, direct CO2 capture from the air, together with subsequent sequestration, would eventually have to be introduced in addition to 90% reductions in global carbon emissions.

I purposely kept emissions constant after 2050 in my idealized scenarios to illustrate that cutting emissions by some prescribed amount by 2050 is in and of itself not sufficient to deal with the problem of global warming. Even if we maintain global carbon dioxide emissions at 90% below current levels, we eventually break the 2°C threshold. This is because the natural carbon dioxide removal processes can’t work fast enough to take up the emissions we emit to the atmosphere year after year. Any solution to global warming will ultimately require the world to move towards net zero emissions carbon which requires the introduction and global scale up of negative emission technology.

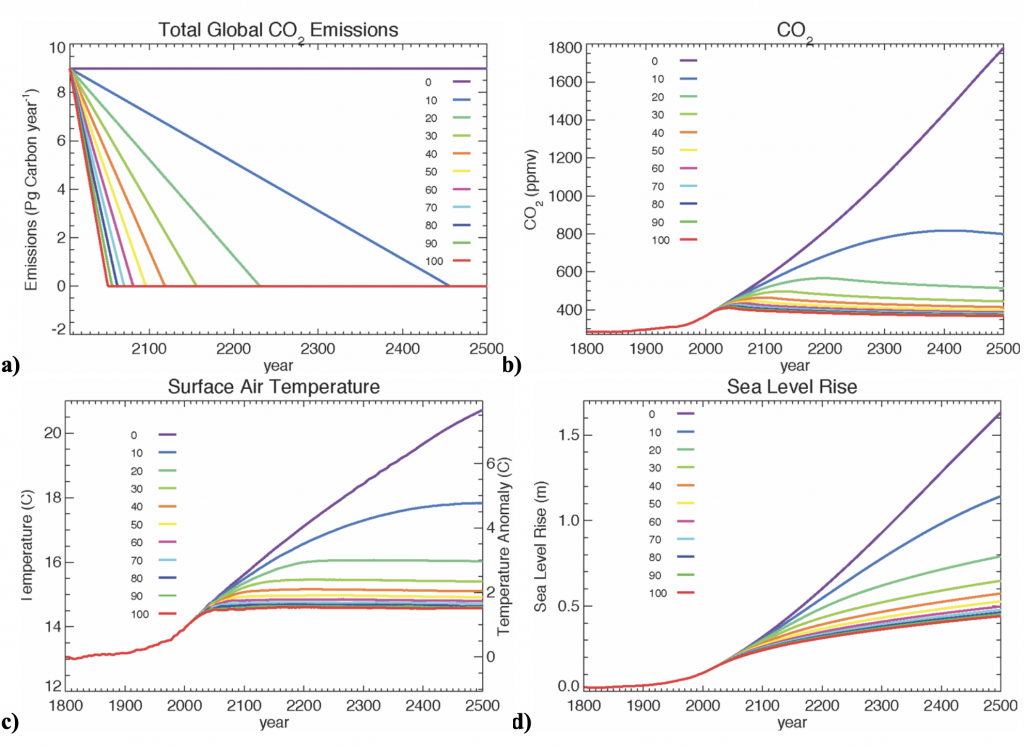

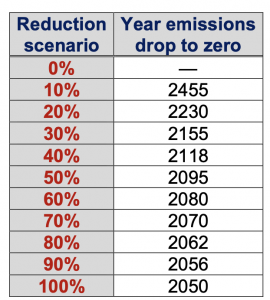

Figure 3: As in Figure 2 but the emissions in (a) continue the linear decrease until zero emissions are reached. The year in which zero emissions is reached is indicated in the table below.

Now let’s examine the effects of another hypothetical international policy option that starts from the results obtained in the previous suite of experiments at 2050 but now continues to linearly decrease emissions at the same rate until zero emissions are reached. The resulting emissions are shown in Figure 3a and the date at which emissions fall to zero is given in table to the right.

Now let’s examine the effects of another hypothetical international policy option that starts from the results obtained in the previous suite of experiments at 2050 but now continues to linearly decrease emissions at the same rate until zero emissions are reached. The resulting emissions are shown in Figure 3a and the date at which emissions fall to zero is given in table to the right.

If we keep emissions on a linearly decreasing emissions path to carbon neutrality, it turns out that in the UVic model about 45% or larger reductions (relative to 2005 levels) are required by 2050 if we do not wish to break the 2°C threshold. And peak atmospheric carbon dioxide levels reach a little over 450 ppm before settling down to slightly above 400 ppm. Notice that in all cases, even though emissions have gone to zero, sea level continues to rise. It’s further important to note that these simulations were conducted and published in 2007 and assumed the hypothetical scenario of an immediate curtailing of emissions. The reality is global fossil carbon emissions (excluding land use emissions) were 10.1 GtC (billions of tonnes of carbon) in 2021 which is a 25% increase from 2005 levels (when they were 8.1GtC).

In this section I have tried to emphasize that the only means of stabilizing the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is for humanity to achieve net zero carbon emissions. While the implementation of nature-based solutions provides some additional time before net zero must be reached to avoid breaking the 2°C guardrail, there is a danger that such efforts are being overly promoted by governments and industry to allow them to maintain the status quo of oil, gas and coal exploration and combustion.

It’s a question of timescale

Millions of years ago when the atmosphere had much higher concentrations of carbon dioxide, trees, ferns, and other plants were abundant. These plants used the sun’s energy, together with carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and water, to create glucose or sugar and release oxygen back to the atmosphere (photosynthesis). As the years went by, plants would grow and die, and some of these dead trees and other vegetation would fall into swampy waters depleted in oxygen. In this environment, the organic matter only partially decayed and so turned into peat, a precursor for coal formation. Over time, shallow seas covered some of the swampy regions, depositing layers of mud or silt. As the pressure started to increase, the peat was transformed, over millions of years, into brown coal, then soft coal, and finally hard coal.

Millions of years ago when the atmosphere had much higher concentrations of carbon dioxide, trees, ferns, and other plants were abundant. These plants used the sun’s energy, together with carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and water, to create glucose or sugar and release oxygen back to the atmosphere (photosynthesis). As the years went by, plants would grow and die, and some of these dead trees and other vegetation would fall into swampy waters depleted in oxygen. In this environment, the organic matter only partially decayed and so turned into peat, a precursor for coal formation. Over time, shallow seas covered some of the swampy regions, depositing layers of mud or silt. As the pressure started to increase, the peat was transformed, over millions of years, into brown coal, then soft coal, and finally hard coal.

A similar process occurred within shallow seas where ocean plants (e.g., phytoplankton) and marine creatures would die and sink to the bottom to be buried in the sediments below. Over millions of years, the sediments hardened to produce sedimentary rocks, and the resulting high pressures and temperatures caused the organic matter to transform slowly into oil or natural gas. The great oil and natural gas reserves of today formed in these ancient sedimentary basins.

Today when we burn a fossil fuel, we are harvesting the sun’s energy stored from millions of years ago. In the process, we are also releasing the carbon dioxide that had been drawn out of that ancient atmosphere (which had much higher levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere than today). So, unless we can actually figure out a way to speed up the millions of years required to sequester carbon from the atmosphere and to convert dead plants back into peat and then coal (or oil and gas) the idea that we can somehow stop global warming solely through nature-based solutions isn’t realistic.

Nevertheless, and I reiterate, there are many positive reasons for planting new forests (afforestation), replanting old forests (reforestation), or reducing the destruction of existing forests (deforestation), including the restoration of natural habitat and the prevention of loss of biodiversity. However, trees only store carbon over the course of their lifetime. When these trees die, or if they burn, the carbon is released back to the atmosphere.

The danger of over reliance on nature based solutions

While nature-based solutions have an important role to play in climate change adaptation and the preservation of biodiversity, there is a growing danger that governments, industry and the general public will come to rely on them as a means to maintain the status quo.

Let’s take British Columbia’s LNG experience as an example.

In the lead up the the 2013 provincial election I repeatedly pointed out the economic and environmental folly of somehow believing that BC would build prosperity through liquifying natural gas and shipping it to Asia. In fact, I quantified my concerns in one of the first blog posts I wrote in the BC Legislature. British Columbia residents were being told that at least five major LNG facilities would be built in BC by 2020. Today we have none, so I would suggest that my concerns about the economics of LNG were spot on.

In the lead up the the 2013 provincial election I repeatedly pointed out the economic and environmental folly of somehow believing that BC would build prosperity through liquifying natural gas and shipping it to Asia. In fact, I quantified my concerns in one of the first blog posts I wrote in the BC Legislature. British Columbia residents were being told that at least five major LNG facilities would be built in BC by 2020. Today we have none, so I would suggest that my concerns about the economics of LNG were spot on.

In 2018, when it was clear that BC’s plans for LNG were not going to materialize, the BC NDP picked up where the BC Liberals left off and further sweetened the tax credit regime for LNG Canada, the one remaining major LNG company left in BC. It was clear to me that British Columbia could not meet its legislated greenhouse gas reduction targets if the LNG Canada project was ever built and I wrote a detailed blog post pointing out that it was time for both the BC NDP and the BC Liberals to level with British Columbians about LNG. The BC NDP government remained adamant that BC could still reduce emissions to 40% below 2007 levels by 2030. I remained skeptical and feared that this target can only be achieved through creative carbon accounting and appealing to “nature-based solutions”. I believe I was and remain correct. The analysis above and my earlier blog posts should make that obvious. And nobody should be surprised to see Shell Canada now promoting its efforts to ensure “the protection and restoration of natural ecosystems such as forests, grasslands and wetlands” as a central component to its greenhouse gas mitigation strategy. Of course, there is no mention of greenhouse gas emissions from the ever increasing area burnt by Canadian wildfires, nor the emissions being triggered as permafrost thaws and the previously frozen organic matter begins to decompose.

The Darkwoods Forest Carbon project offers a glimpse into what is likely being considered by BC government and industry decision-makers as a means of offsetting emissions from the natural gas sector. The problem with this is threefold.

First, claiming that the preservation of a forest should be considered a carbon offset using an argument that the wood would otherwise be harvested is a bit like me say to you: “give me $10,000 or I will buy a gas-guzzling SUV”! Second, if you want to claim a carbon credit for planting a tree, then you have to also accept a debit if that tree, or another, burns down. Third, there is no international mechanism to get credit for such a nature-based offset and these are purely considered voluntary.

Summary

In this post I have tried to outline the important role that nature-based climate solutions play amid the suite of policy options available to government and industry. The cautionary tale is that while these represent important contributions to a jurisdiction’s overall climate change adaptation and mitigation strategy, they cannot take away from the requirement to decarbonize energy systems immediately. As outlined in a recent article published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B by researchers from Oxford University in the UK, “there are concerns over their reliability and cost-effectiveness compared to engineered alternatives, and their resilience to climate change.”

For years I have noted that the signing of the Paris Agreement in 2015 had immediate consequences for oil, gas and coal exploration. At the time of its signing, and given the availability of existing technologies, the Paris Agreement translated to the notion that effective immediately, no new oil, gas or coal infrastructure could be built anywhere in the world if we want to keep warming to below 2°C. This follows since such major capital investments have a long payback time; you don’t build a natural gas electricity plant today only to tear it down tomorrow. Socioeconomic inertia in the built environment also suggests that the capital stock turnover time would be decades, not years.

Nature based-solutions are really a natural branch of other so-called Carbon Dioxide Removal geoengineering projects. Another solution that has received some attention of late concerns increasing the alkalinity of surface waters through dissolution of limestone. This geo-engineering fix was one of many examined by the IPCC in a 2005 special report assessing the possibility of capturing and storing carbon dioxide. To sequester 1 kilogram of carbon dioxide without the negative effects associated with acidification 3.5 kilograms of calcium carbonate (limestone) would have to be artificially dissolved in the ocean. Today, about 6.6 Gt of limestone is mined annually. If the entirety of this global production was dissolved in the ocean, about 1.9 Gt of carbon dioxide could be sequestered annually (or 0.5 Gt of carbon equivalent). This represents about 5% of the world’s 2021 global carbon dioxide emissions. A twenty-fold increase in limestone mining to sequester our present-day emissions would have enormous energy implications (with their concomitant emissions), not to mention the potential environmental impacts of such expanded mining activities. We would also have to stop producing cement, which uses this limestone, throughout the world, meaning that concrete could no longer be used in construction. It should be clear that attempting to modify surface alkalinity using the world’s limestone resources is not a serious proposition to combat global warming.

Nature based-solutions are really a natural branch of other so-called Carbon Dioxide Removal geoengineering projects. Another solution that has received some attention of late concerns increasing the alkalinity of surface waters through dissolution of limestone. This geo-engineering fix was one of many examined by the IPCC in a 2005 special report assessing the possibility of capturing and storing carbon dioxide. To sequester 1 kilogram of carbon dioxide without the negative effects associated with acidification 3.5 kilograms of calcium carbonate (limestone) would have to be artificially dissolved in the ocean. Today, about 6.6 Gt of limestone is mined annually. If the entirety of this global production was dissolved in the ocean, about 1.9 Gt of carbon dioxide could be sequestered annually (or 0.5 Gt of carbon equivalent). This represents about 5% of the world’s 2021 global carbon dioxide emissions. A twenty-fold increase in limestone mining to sequester our present-day emissions would have enormous energy implications (with their concomitant emissions), not to mention the potential environmental impacts of such expanded mining activities. We would also have to stop producing cement, which uses this limestone, throughout the world, meaning that concrete could no longer be used in construction. It should be clear that attempting to modify surface alkalinity using the world’s limestone resources is not a serious proposition to combat global warming.

So in summary, despite the many benefits of nature-based solutions, what is required to keep global warming to below 2°C (or, frankly, to stabilize it at any level), is the immediate transition towards the decardonization of global energy systems along with the widespread introduction of negative emission technology, such as direct air carbon capture and deep underground storage. At this stage, I am of the belief that this remains the only hope humanity has for a long term solution to this problem. We can take comfort in the very real successes of nature-based solutions, and their many co-benefits, but we cannot take our eyes off the scale of the challenge before us. Fortunately, all the solutions are known. It is a matter of individual, institutional, corporate and political will as to whether or not we will achieve the goals of net zero emissions in the future.

Privilege, agency, and the climate scientist’s role in the global warming debate

Background

One of the biggest surprises I found upon my return to the University of Victoria after spending 7 1/2 years in the BC Legislature was the overall increase in underlying climate anxiety being experienced by students in my classes. I’ve been teaching at the university level since the mid 1980s and for most of this time, the students in my classes considered global warming to be an esoteric and highly uncertain future threat. While some would express concerns about the growing concentrations of atmospheric greenhouse gases, very few understood, or even cared, how climate change could hypothetically affect them. It was always a problem that others, somewhere else in the world, might have to deal with sometime down the road – but not any more. My experience with this new generation of undergraduates is that they are both very aware of, and deeply troubled by, the threat of global warming. I am beginning to detect a sense of hopelessness and despair within growing numbers of youth. And this troubles me immensely.

For many years I, and my climate science colleagues around the world, spoke truth to power as we continually raised concerns about the ongoing consequences of dumping millions of tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere every year. But our warnings fell on deaf ears, or at least ears damaged by the never ending stream of spin, obfuscation and rhetoric being offered up by lobbyists, vested interests, charlatans and others desperate to maintain the fossil-fuel status quo. Yet those days are gone. So much has changed.

Perhaps the most notable increase in public awareness can be attributed to Greta Thunberg and her Skolstrejk för klimatet (School strike for climate). Starting from her lone Friday demonstrations on the steps of the Swedish parliament in August 2018, her movement quickly gained international attention leading to locally-organized Fridays for Future demonstrations around the world (see Figure 1 for images from a Friday, September 19, 2019 demonstration on the lawn of the BC Legislature).

Figure 1 : Four images taken on Friday, September 20, 2019 at a Global Week for Future demonstration on the lawn of the BC Legislature.

At the same time, extreme weather and climate extremes are seemingly becoming the norm rather than the anomaly, with hardly a day going by without a weather disaster somewhere in the world headlining the nightly news. And while in the past, these extreme weather events may have seemed to be someone else’s problem living elsewhere in the world, today no one is immune. Even meteorological terms like “heat domes”, “atmospheric rivers” or the “polar vortex” are becoming commonly used in casual conversation.

The cumulative efforts of so many over so many years in pointing out the importance of curtailing greenhouse gas emissions is finally paying off. Public awareness and desire for action is no longer a barrier to advancing climate policy. For example, one Pew Centre global survey spanning 17 countries in Europe, the Asia-Pacific, and North America indicated that 80% of people surveyed were “willing to make [a lot of or some] changes about how [they] live and work to help reduce the effects of global climate change” (Bell et al., 2021). The greatest barrier, in my view, remains political will. Too many of our elected representatives end up treating politics as a lifelong career instead of a sense of civic duty wherein you step in for a few years, do your part, then step out and let others take over. After a while, one might cynically expect such career politicians to naturally start focusing more on populist and short term policy measures that can successfully be developed and implemented prior to the next election. It would allow that politician to identify short term successes as direct evidence that they were delivering results for their constituents.

By its very nature, climate policy requires a much longer term perspective to be taken. It requires recognition that today’s decision-makers wont have to live the consequences of the climate-related decisions (or lack thereof) that they make. Yet I have always believed that global warming represents the greatest opportunity for innovation, creativity and economic prosperity the world has ever seen since every environmental challenge can also be viewed as an opportunity for innovation and creativity as we seek to address the underlying challenge. Instead of dwelling on the scale of the challenge and hence its apparent hopelessness, which only feeds an individual’s climate anxiety, it can be incredibly empowering to pivot to a focus on developing climate solutions. And herein lies an opportunity for the climate science community.

Climate Anxiety

Climate anxiety is a very real psychological and emotional response to concern about uncertain future climate change impacts (American Psychological Association, 2017, Doherty and Clayton, 2011). Defined as a chronic fear of climate or environmental doom, an individual’s chronic climate anxiety is magnified by extreme weather and climate events that have been experienced personally and/or by those in their close networks.

For example, climate anxiety in North America increased in the summer of 2021 because of intense, record-breaking heatwaves and wildfires (Bratu et al., 2022). As well, increased climate anxiety was almost certainly triggered in those who experienced September 2022’s widespread destruction caused by Hurricane Fiona and Ian’s historic winds, wave activity and storm surge.

Figure 2: Canadian Space Agency satellite images taken on August 21, 2022 (left) and September 25, 2022 (right). Extensive coastal erosion of Prince Edward Island was caused by historic storm surge and wave activity associated with Hurricane Fiona.

Figure 2: Canadian Space Agency satellite images taken on August 21, 2022 (left) and September 25, 2022 (right). Extensive coastal erosion of Prince Edward Island was caused by historic storm surge and wave activity associated with Hurricane Fiona.

Climate scientists are not immune to climate anxiety. Many within our community have felt compelled to speak out publicly regarding the causes, consequences, and seriousness of global warming. Others have signed petitions, penned letters, written books and commented on social media sites. However, few have actively sought election to government office. This is unfortunate as I continue to believe that political will remains the greatest barrier to advancing climate policy including the decarbonization of global energy systems. But instead of helping to generate that political will, a large cohort of the climate science community, in an attempt to deal with their own climate grief, has heightened rather than alleviated climate anxiety in civil society.

Through this article, I hope to encourage that community to reflect upon the privilege and agency they have to refocus and mobilize their efforts towards advancing climate solutions within society, and to appeal to their sense of civic duty to inspire more to seek elected office. In particular, I argue that:

- Inaccurate scientific messaging associated with the 2018 IPCC Global Warming of 1.5°C report is feeding climate anxiety, and this is leading to despair in youth.

- There are more effective ways for scientists, armed with privilege and agency, to advocate for climate policy than fear-based messaging and civil disobedience.

As Albert Einstein famously noted: “Those who have the privilege to know have the duty to act, and in that action are the seeds of new knowledge.” After reading the rest of this blog, I hope you agree that this quote could be expanded with an additional sentence. “And as the new knowledge grows, the solutions to global warming are revealed.”

Scientific messaging is feeding climate anxiety

The 2018 IPCC Special Report outlining greenhouse gas emission pathways to limit warming to 1.5°C above preindustrial levels (IPCC, 2018) almost certainly contributed to an escalation of overall climate anxiety in recent years. The Special Report was a response to an invitation from signatories to the UNFCC as part of the Paris Agreement. The 2015 Paris Agreement, joined by 193 member states, has the specific goal of:

Holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change (UNFCC 2015).

The aspirational 1.5°C target was added in response to lobbying by small island states (and their allies).

While the scientific community responded by outlining pathways to mitigate warming to 1.5°C in (IPCC, 2018), the subtleties embedded within the report seem to have been lost in its dissemination to the public. It is well known that the world has already warmed by 1.2°C since preindustrial times, and if we immediately eliminated all fossil fuel combustion worldwide, we would warm by an additional 0.5°C (IPCC 2021; see Figure 2) as the direct and indirect cooling global effects of aerosols (also associated with fossil fuel combustion) dissipate through gravitational settling and precipitation scavenging. The Earth would warm further as we equilibrate to the present 508 PPM CO2e (NOAA 2022) greenhouse gas loading in the atmosphere, and that is not counting the permafrost carbon feedback which could add another 0.1° to 0.2°C this century to committed warming (Macdougall et al, 2013).

In other words, meeting the 1.5°C target requires an immediate global scale up of negative emissions using technologies that have yet to be developed. Given socioeconomic inertia in our built environment (Matthews and Weaver, 2010), the scale of negative emissions required, and the preponderance of more urgent political priorities (i.e. healthcare, housing, inflation, the economy, the war in Ukraine and so forth), it is not possible for the world to meet the 1.5°C target.

Figure 3: Observed global warming (2010-2019 relative to 1850-1900) and the contribution to this net warming by observed changes to natural and anthropogenic radiative forcing. Reproduced from IPCC (2021).

Climate anxiety is also fueled by media messaging related to the perception of a looming climate ‘crisis’ (Crandon et al., 2022). Take the anxiety effect of popular messaging related to the aspirational goal of remaining below a 1.5°C global warming threshold (IPCC, 2018). “We have only 12 years left to limit climate change catastrophe, warns UN” was the headline of a story published in the Guardian on October 8, 2018; “Only 11 years left to prevent irreversible damage from climate change, speakers warn during general assembly high-level meeting” was the headline of a press release issued by the United Nations on March 28, 2019 during its 73rd session (UN, 2019); “Climate change: 12 years to save the planet? Make that 18 months” was the headline of a BBC News story on July 24, 2019 (BBC, 2019).

Climate anxiety is also fueled by media messaging related to the perception of a looming climate ‘crisis’ (Crandon et al., 2022). Take the anxiety effect of popular messaging related to the aspirational goal of remaining below a 1.5°C global warming threshold (IPCC, 2018). “We have only 12 years left to limit climate change catastrophe, warns UN” was the headline of a story published in the Guardian on October 8, 2018; “Only 11 years left to prevent irreversible damage from climate change, speakers warn during general assembly high-level meeting” was the headline of a press release issued by the United Nations on March 28, 2019 during its 73rd session (UN, 2019); “Climate change: 12 years to save the planet? Make that 18 months” was the headline of a BBC News story on July 24, 2019 (BBC, 2019).

To amplify the urgency of further climate action, “Climate Clocks” were developed that purported to count down days until it was too late to avoid the worst impacts of global warming (see here and here). It is unclear how watching a countdown to catastrophe would do anything other than increase climate anxiety and instill a sense of hopelessness and despair. Political rhetoric from those with large followings, such as when Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez proclaimed “The world is going to end in 12 years if we don’t address climate change” (USA Today, 2019), also contributes to increasing climate anxiety.

To amplify the urgency of further climate action, “Climate Clocks” were developed that purported to count down days until it was too late to avoid the worst impacts of global warming (see here and here). It is unclear how watching a countdown to catastrophe would do anything other than increase climate anxiety and instill a sense of hopelessness and despair. Political rhetoric from those with large followings, such as when Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez proclaimed “The world is going to end in 12 years if we don’t address climate change” (USA Today, 2019), also contributes to increasing climate anxiety.

![]() Inherent in the 12 years left narrative, and the IPCC 1.5°C report is the implied notion that there is something magical about the number 1.5°C. Of course, there is no scientific rationale to justify an acceptable warming threshold of 1.5°C instead of 1.3°C or 1.672°C. Any defined level of ‘acceptable’ warming obviously involves an assessment of societal values and those will clearly be different depending on where you live in the world.

Inherent in the 12 years left narrative, and the IPCC 1.5°C report is the implied notion that there is something magical about the number 1.5°C. Of course, there is no scientific rationale to justify an acceptable warming threshold of 1.5°C instead of 1.3°C or 1.672°C. Any defined level of ‘acceptable’ warming obviously involves an assessment of societal values and those will clearly be different depending on where you live in the world.

In fact, even the 2°C threshold for acceptable warming originally only entered the public arena shortly after the IPCC released its Second Assessment Report and prior to the establishment of the Kyoto Protocol. In 1996, the Council of the European Union concluded:

The Council recognizes that, according to the IPCC S.A.R., stabilization of atmospheric concentrations of CO2 at twice the pre-industrial level, i.e. 550 ppm, will eventually require global emissions to be less than 50% of current levels of emissions; such a concentration level is likely to lead to an increase of the global average temperature of around 2°C above the pre-industrial level.

And:

Given the serious risk of such an increase and particularly the very high rate of change, the Council believes that global average temperatures should not exceed 2 degrees above pre-industrial level and that therefore concentration levels lower than 550 ppm CO2 [carbon dioxide] should guide global limitation and reduction efforts. This means that the concentrations of all greenhouse gases should also be stabilized. This is likely to require a reduction of emissions of greenhouse gases other than CO2 in particular CH4 [methane] and NO2 [sic; nitrous oxide].

Ironically, it was inconsistent on the one hand, for the EU Council to advocate for carbon dioxide to be stabilized at or below 550 ppm with emissions eventually dropping to less than 50% of 1996 levels, while on the other hand, arguing for the 2°C threshold not to be exceeded.

While ambitious goal-setting can in theory be an effective motivator of action (Locke and Latham, 2002), in practice, alarmist media reframing (Ereaut and Segnit, 2006) of failure to remain below the 1.5°C goal into a scenario of impending doom has become quintessential fuel for personal climate anxiety. Taken in the collective across society, climate anxiety driven by personal concern and amplified by poorly calibrated media messaging is quickly emerging as a dominant factor in the collective zeitgeist of the Anthropocene (e.g. Crutzen 2006, Hickman et al 2021, Wray 2022).

Given that most of today’s decision-makers will not be around to be held accountable for their action, or lack thereof, towards meeting various targets set well into the future, a more appropriate framing and scientifically justifiable statement is for society to collectively do what we can to avoid as much warming as possible. Every tenth of a degree warming avoided reduces our collective climate risk and, by corollary, our overall collective climate anxiety.

But this still doesn’t address how individual climate anxiety can be reduced.

A far more constructive approach would be for the scientific community to turn our collective attention to climate solutions, not climate fear mongering or climate alarmism. Take the recent viral Tik Tok video showing Nasa Scientist Dr. Peter Kalmus prior to getting arrested after chaining himself to a JP Morgan Chase building in Los Angeles. The emotion in Dr. Kalmus’ voice indicates that he is likely dealing with his own climate anxiety, but I question whether or not the message in his viral video did anything more than increase the level of anxiety within children and youth worldwide:

“So, I am here because scientists are not being listened to. I am willing to take a risk for this gorgeous planet. That sucks, and we’ve been trying to warn you guys for so many decades now we are heading towards a catastrophe. And we are being ignored, the scientists of this world are being ignored, and it’s got to stop. We are going to lose everything, and we are not joking. We are not lying; we are not exaggerating. This is so bad everyone that we are willing to take this risk and more and more scientists, and more and more people are going to be joining us. This is for all the kids of the world — all of the young people, all of the future people. This is so much bigger than any of us. It’s time for all of us to stand up and take risks and make sacrifices for this beautiful planet that gives us life.”

At no point were any solutions posed, any positive actions suggested, or any personal climate risk reduction advocated for. The scientists involved likely believed that they were raising public awareness of the seriousness of global warming. Yet I argue that these same scientists abdicated their position of power and privilege by inadvertently pretending to be on the same footing as those most affected by climate change. In doing do, the scientists did little more than stoke the fires of climate anxiety when they had agency to facilitate constructive change both within their public engagements, as well as their own personal choices.

It’s also long been known that fear based messaging does not work in terms of motivating personal climate action (e.g., O’Neill and Cole (2009) , Stern (2012), Climate Tracker (2017). In fact, many simply disassociate themselves from the issue. Others, of course, take the fear to heart and it feeds their underlying climate anxiety.

Articles like McKay et al., 2022, with provocative, if not highly speculative, titles may attract media attention in the lead up to an annual UNFCCC COP event. But they are often framed as opinion or expert assessment and so are often highly controversial and not representative of broad scientific consensus. Extremely low probability, perhaps even impossible, but certainly poorly understood tipping point scenarios often end up being misinterpreted as likely and imminent climate events. The nuances of scientific uncertainty, the differences between hypothesis posing vs hypothesis testing, and the proverbial “implications of this work” throw away statements, wherein scientists take creative license with speculative possibilities, are all lost on the lay reader as the study goes viral across social media.

More recently, some activists have even called on the scientific community to engage in more civil disobedience (e.g., Capstick et al., 2022, Earth.org, 2022) arguing that it is effective and leads to change. Once more, I am not sure how activist scientists with agency help advance the necessary solutions and believe that the time for such activism has long passed. Governments around the world have committed to climate action but are struggling to advance the various solutions required for the low carbon economies of tomorrow. They need help, ideas, solutions and ongoing support and the scientific community is ideally positioned to assist in this regard.

In fact, many look to the climate science community for leadership on greenhouse gas mitigation and do so with dismay when they see these same scientists jetting off to various conferences, UNFCCC COP/IPCC meetings and workshops at exotic locations around the world. How many thousands of people attended the 26th Conference of Parties meeting of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in Glasgow in 2021? How many attended the 27th meeting in Sharm el-Sheikh in 2022? Was their presence really necessary? Climate scientists, with their privilege and agency, not only have a responsibility to assist identifying and implementing climate solutions; they also need to model the climate leadership they are calling on others to follow. Failing to do so sends the wrong message, a message that undermines the prevailing narrative that we are in a “climate emergency”.

More effective ways for scientists to advocate for climate policy

The climate science community operates from a position of privilege in the public discourse of climate change science, its impacts and solutions. Whether it be by participating in the writing of IPCC reports or our own research, climate scientists have defined the scale of the global warming challenge, outlined pathways to decarbonization of our energy systems, and documented a suite of future impacts, many of which would be very detrimental to future societies. We’ve also quantified the climate risk to our natural and built environment. Armed with this knowledge, climate scientists, more than most, are well-informed and so have agency in the advancement of climate solutions. But when climate scientists participate in civil disobedience or do little more than criticize others for inaction, they abdicate that position of privilege and agency by pretending to be on the same footing as others in society who are not as well informed on the nuances of climate change. As such, rather than alleviating their own, and broader society’s, climate anxiety, they fuel it further by inadvertently ratcheting up the rhetoric with nothing to offer in terms of overall solutions or risk reduction. I firmly believe that the climate science community has a duty and responsibility to become more actively engaged in the delivery of climate solutions in whatever form they feel most comfortable work with (i.e., nature-based, technological, socioeconomic or policy solutions).

At the same time, the scientific community must be reminded that they are but one stakeholder in the global warming debate. Whether or not society wishes to respond to the challenge of global warming really boils down to one question. Do we the present generation owe anything to future generations in terms of the quality of the environment we leave behind? Yes or No? Science cannot answer this question; but it can help articulate the expected consequences of action or inaction. Science can also inform decision makers by pointing out that if the answer to the above question is yes, dramatic GHG reductions (both through the decarbonization of energy systems and the introduction of negative emission technology) must commence now. Waiting until the future to start reducing emissions means waiting until it is too late.

While the answer to the above question is fundamentally personal, most almost certainly would respond yes, particularly those who have children. Yet some would disagree. For example, “Some evangelicals argue that global warming is of little concern when the end times are approaching. Indeed, it could even be proof of it” (Gander, 2019); Fatalists may believe that what will occur in the future is inevitable, perhaps even a manifestation of God’s will, and so believe that an individual’s actions or choices will have no effect on the direction we are heading. Libertarians may focus on the importance of individual freedoms, express concern about government overreach and regulation and may advocate for a laissez-faire approach to climate policy. There might be some who might answer yes to question, but their deep suspicion of environmentalists may make them question the urgency of dealing with global warming. Then of course there are those who will have been swept up in the various conspiracy theories so prevalent on the internet these days. Fortunately, the Pew survey cited above (Bell et al., 2021) allows us to estimate that it is only about 20% of the population who will likely object to the advancement of climate policy. And so, I am of the firm belief that engaging with this audience is counter-productive and a waste of a climate scientist’s time.

Instead of trying to persuade the unpersuadable, participating in civil disobedience or publicly demanding government take unspecified actions it would be far more productive if the scientific community, turned their attention to the development and advancement of climate solutions. This can be accomplished in any one of a number of ways. For example:

- Supporting progressive government policy vocally and publicly once it has been introduced;

- Running for office;

- Advocating for constructive solutions in recognition that we have agency and we occupy a position of privilege in society.

Given the emergence of social media in this post-truth age we are seeing more and more populist policies globally wherein decisions are made first, and then evidence (real or imagined) is sought after the fact to support an ideological agenda — this is what I call decision-based evidence-making, the antithesis to the scientific method. Scientists are driven by the quest to understand the world around us. We are driven by evidence. We identify problems and then take steps to solve these problems using reproducible techniques. Central to who we are as scientists is the notion of evidence-based decision-making. We understand this notion and react strongly to decision-based evidence-making, the antithesis to the scientific method. I truly believe our community has an inherent responsibility to exhibit the necessary leadership (especially through our own behaviour) to ensure that we play a constructive role in identifying solutions to the environemental problem that we have spent so many decades studying.

Finally, a co-benefit our community will warmly welcome in the move towards a climate-solutions focus, is the amelioration of our own climate anxiety (not to mention broader societal climate anxiety). I say this from personal experience, having worked in the field since the 1980s. Climate scientists, like others in the general public, often also struggle with the notion of climate anxiety and grief. But unlike others in the general public, our community holds agency and a position of privilege in the global warming debate. Rather than denying this agency and privilege I am hopeful that as a community we will collectively rise to the myriad opportunities global warming has afforded us for constructive public engagement and the betterment of society.

In the weeks ahead, I hope to expand upon these initial ideas by offering more concrete examples of engagement and responding to any feedback coming my way from this post.

Advancing lasting policy through good governance

It’s election season here in the CRD and true to form, political rhetoric is escalating. In the City of Victoria, for example, there is an ongoing divisive debate over the so-called Missing Middle Housing Initiative. Younger generations affected by the rental crisis and the lack of affordable housing are being pitted against homeowners (often assumed to be from an older generation).

In my view, the debate is not actually focused on the key questions that need to be answered:

- Will the proposed initiative address the issue of affordability? In other words, is the proposed solution meeting a desired outcome?

- Is the initiative being advanced in a way that brings people with you in the process?

- What is the role of council and why is this new initiative required?

Compelling arguments are being advanced in support of both sides of the first question and some believe that this is where the public controversy arises. In my view, it isn’t.

The term “missing middle housing”, was first coined by Daniel Parolek in 2010 and expanded upon in his book Missing middle housing : Thinking big and building small to respond to today’s housing crisis, published in 2020. It’s defined as “house-scale buildings with multiple units in walkable neighbourhoods”, and it was designed to address sprawling US car-dependent communities.

Many I have spoken with have long supported the notion of missing middle housing, without knowing the slogan. In fact, successive Victoria councils have a longstanding track record of allowing for, and even promoting, such developments. One only need drive along Shelbourne Street to find myriad townhouse developments built in recent years, or travel along Rockland Avenue to witness stately mansions from the early 1900s that have been preserved and transformed into multi-family units.

Moving to question 2, I believe the answer is demonstrably no. In general, any policy consultation process that ends up pitting one group against another is destined to divide rather than unite our community. And that is what we are seeing in the missing middle debate in my view.

Such societal polarization is often reinforced by some in the so-called progressive movement who ironically don’t realize that their communication/activism tactics are quite similar to those employed by elements of the alt right. These include being intolerant of opposing views, making assertions – not grounded in evidence – to justify a cause, attacking people who disagree with them on social media, and civil disobedience to hopefully increase public awareness to their cause. Groups that are intolerant of the views of others, whether they be on the left or the right, ultimately just reinforce British Columbia’s longstanding reputation for societal polarization and pendulum politics.

Pendulum politics occurs when an angry electorate mobilizes, often egged on by an opposition party/individual or parties/individuals, to unseat those holding elected positions. Consequently, local, provincial and federal governments get summarily turfed out in elections and the party or individual(s) on the other side of the political spectrum form government or the majority on council. More often than not, the so-called baby is thrown out with the bathwater as the new government or council begins to undo the work of the previous government or council to fulfill their election campaign promises.

One solution to ongoing pendulum politics is to put in place a form of proportional representation like what already exists in more than 90 countries, and the majority of western democracies, worldwide. At the council level, this translates to a ward system that ensures unique neighbourhoods within a municipality are properly represented at the council table. Regional District electoral systems already operate on a ward system. For example, the Cowichan Valley Regional District has representation from 9 different electoral areas; the Nanaimo Regional District has representation from 7 different electoral areas.

But we have neither of these systems in place, and so we must work within the system that we have. And this brings me to question 3.

Local governments are created under British Columbia’s Local Government Act and municipalities, such as Victoria or Saanich, are empowered by British Columbia’s Community Charter which provides:

- “a legal framework for the powers, duties and functions that are necessary to fulfill their purposes,

- the authority and discretion to address existing and future community needs, and

- the flexibility to determine the public interest of their communities and to respond to the different needs and changing circumstances of their communities.”

Obviously, zoning is one of the most important functions of an elected council. The biggest issue with the missing middle initiative is that council are proposing to pass a highly divisive, one-time, city-wide zoning change a few days before the next civic election. Associated with the initiative is the delegation of development approval to staff. In essence, Mayor and Council would be able to deflect any political accountability to their staff.

Mayors and their councils are elected to represent and meet the needs of those residing within each of our unique and diverse neighbourhoods. They are elected to listen to all residents, not just their political supporters, as they propose and approve policies that unite, rather than divide, our communities.

In my view council have chosen to abdicate their public, and hopefully transparent, decision-making process to staff who are not accountable to the electorate. In addition, it makes little sense for Victoria, with a population of only 85,792 (2016 census), the seventh most densely populated (4,406 people per square kilometre — 2016 census) municipality in Canada, to pretend they can go it alone to solve the affordability issue in our region. What is needed is a coordinated regional housing strategy.

It strikes me that what we are witnessing is divisive politics instead of good governance, especially since such an important issue is being debated just over a month before the next local government elections with virtually all the present council having declared that they are not seeking re-election. Who will be held accountable for a decision on the Missing Middle Initiative? Nobody. The truth is, council have already been implementing and could further expand upon, the issue of missing middle housing if good governance was placed ahead of divisive political posturing.

Another example, which serves to illustrate just how dysfunctional the recent decision-making process on Victoria council is concerns the recent pronouncement that all new construction from 2025 must be “zero carbon” producers by 2025. This means that the era of oil, gas or propane heating is over in new construction in Victoria. As someone who has been speaking out publicly on the need to reduce GHG emissions since the early 1990s, obviously I support this policy. In fact, CleanBC, British Columbia’s climate action plan, already requires the same throughout BC by 2030. But once more, the way Victoria council brought this forward is almost a textbook example of what not to do to advance climate policy. While other jurisdictions are exploring similar proposals for early adoption, Victoria decided to go it alone amid rising affordability, inflation concerns and a divisive debate on the Missing Middle Housing Initiative.

How processes like this play out is predictable. A new Mayor and Council recognize that the previous Mayor and Council had lost the confidence of the electorate. As evidence for this one only need read the results of the recent governance survey where 81% of respondents stated that they were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with Victoria’s governance. Despite losing the confidence of the electorate, council still decided to debate or pass controversial motions at the 11th hour thereby blindsiding many in our community because the important groundwork to bring people with you was not done in advance. And so pendulum politics kicks in and a new Mayor and Council start to undo the work of the previous Mayor and Council in order to repair the divides within our community.

We’ve seen this happen before in British Columbia. When Premier Campbell brought in the HST without bringing the electorate along with him it spelled the end of his leadership. Now even uttering the words HST is political suicide. This, despite when coupled with a low-income HST rebate program (as was proposed), this form of consumption taxation many would argue represents good fiscal policy.