Environment

Saving Woodland Caribou from extirpation will also save old growth forests

Over the last few months British Columbia’s controversial wolf cull has been the subject of substantial public dialogue. Like most MLAs, I receive ongoing communication from numerous British Columbians questioning the rationale behind the government’s approach. One of the most recent communications I received was from a young woman named Katie. She started off her email saying:

“My name is Katie, and I oppose the wolf cull. In school we learned about predator prey relationships. I know you probably won’t care, and that the government will go ahead with it anyway, but please read this…”

I found her email to be a source of inspiration. Despite her apparent cynicism towards politicians, she took the trouble to express her concerns to me (even though she is not a constituent). Her email struck a chord. I campaigned on a promise of evidence-based decision-making and giving youth in our society, the generation that will have to live the consequences of the decisions my generation is making, a voice in the legislature.

The BC NDP have not contributed anything of significance to this issue. Instead, when questioned they offer up a sense of vague disappointment and an endorsement of “long term habitat protection.” Habitat protection is vital of course, especially for herds that are still relatively healthy, but if that is the only policy we offer the threatened mountain caribou they will all be dead by the time the trees grow back.

The policies that the B.C. Liberals are putting forward are concerningly intertwined with the interests of industry and lack safeguards that would ensure other herds do not follow the South Selkirk and South Peace mountain caribou to the brink of extirpation.

As a member of the legislature it is my job to do more than outright oppose policies I don’t like. I need to be able to substantially contribute to the debate and provide feasible solutions and alternatives. So, I got my office to research the topic, and threatened species management more generally, in great detail. Our subsequent analysis derived from a literature review and many hours of discussions with scientists, including wildlife biologists who have expertise in the area.

When you start rationalizing culling one species to protect another you also introduce an ethical element that needs to be considered alongside the science. Is it ever justifiable to kill one animal in the name of saving another? Science can never answer that question.

Let one of those species become threatened and your situation becomes immensely worse. Ethically, the wolf cull is a horrible response to an ecosystem out of balance. From a management perspective, we need to focus on endangered mountain caribou and the logging practices that got them to where they are today.

Before humans began changing the North American landscape, woodland caribou’s range extended largely across Canada. While northern subpopulations of caribou once roamed in massive herds numbering in the thousands, mountain caribou have always been more sparsely distributed. Mountain caribou survive on a lichen-rich diet, especially in winter months, a food source that is intricately linked to old growth forests. As industrial development and logging activities began to fragment their old growth forest ecosystems, mountain caribou populations began to destabilize. Not only has logging demolished much of their habitat directly, the associated road networks and areas of new growth forest have also brought an influx of moose and white-tailed deer into the ecosystem. Populations of wolves then followed the moose and deer (their primary prey) and caribou (their secondary prey) are now being killed as bycatch. We are scrambling to save herds of mountain caribou on the brink of extirpation because we weakened their natural habitat and made them vulnerable to increased predation. Of this, there is no disagreement within the scientific community.

The future for these threatened caribou is not looking promising; climate change is altering food supplies and habitat conditions, industrial activities are unbalancing ecosystem composition, and human settlement is concentrating the necessity of protected wilderness.

As per requirements enforced under Canada’s Species at Risk Act, the province has protected 2.2 million hectares of forest from logging and road building where populations of caribou are classified as threatened. These areas have immeasurable value for preserving British Columbia’s biodiversity, especially in light of ongoing global warming. But these areas, a substantial fraction of which are old growth, also have substantial commercial value.

Recent Freedom of Infomation documents reveal that the B.C. Liberals met with forest industry representatives when developing plans to save endangered caribou. The Minister of Environment said it is common practice to consult all stakeholders, but I worry that industrial pressures are playing too big a role in habitat allocation. My concern, that I raised last week during Question Period in the British Columbia Legislature, is that vast tracts of forests will stop being preserved the moment the threatened caribou herds go extinct. With their death, the protection of their habitat will no longer be enforceable under the Species at Risk Act.

We need to protect as much land as possible from all human activities so remaining wildlife populations have the space and resources needed to respond to predation and food supply challenges. The cost of restricting industrial development in B.C.’s forests would be expensive in terms of lost revenue, but it would save us having to micromanage every dwindling species.

Where is our provincial government on species protection? Shockingly, we are one of only two provinces (the other being Alberta) that don’t even have any endangered species legislation. Protecting more habitat for our biological diverse ecosystems should be the goal, and creating a provincial endangered species act would be a good place to start.

At the same time, it’s crucial that critical environmental issues are not framed simplistically. There are very real consequences to allowing caribou herds to become extirpated. And one of the most profound of these will be the subsequent logging of remaining stands of British Columbia’s old growth timber.

Protecting Habitat for BC’s Woodland Caribou

Today in the legislature I rose to probe the government’s efforts to preserve natural habitat for BC’s remaining healthy wood caribou herds.

Several additional herds are listed as threatened under Canada’s Species at Risk Act. As such, management actions have been required and subsequently taken. In the discussion reproduced below, the Minister of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations notes that the government has already protected 2.2 million hectares of mountain caribou natural habitat from logging and road building.

I point out that these protected areas have enormous value for preserving British Columbia’s biodiversity, especially in light of ongoing global warming (which I recognized that a rather significant number of BC Liberal MLAs still struggle to believe is occurring). Yet these areas, a substantial fraction of which are old growth forest, also have enormous commercial value.

I wanted to know whether the Minister would commit to the continued protection of these forests even if the caribou herds — those herds which required forests to be protected under Canada’s Species at Risk Act in the first place — become extinct.

For example, there is a very real concern that when the Selkirk herd goes extinct, for example (there are only a dozen or so caribou left), vast areas of valuable, yet presently protected, old growth timber stands will be logged.

I was disappointed in the Minister’s response (which I reproduce below as well).

Please note: when I say “in opposition” in the text, I meant “opposite”. I was gesturing to the BC Liberal side of the house where there are a fair number of MLAs who still have a hard time accepting that the world is warming because of increasing greenhouse gases, despite the fact the scientific community has known this for decades.

Question

A. Weaver: It’s well understood within the scientific community that the loss of natural habitat due to human activities is the primary cause for the disappearing caribou herds in British Columbia. Deforested land provides grazing opportunities for ungulates like deer and moose, which move in along with their natural predators — like, for example, wolves and cougars. Caribou then become the bycatch of these predators.

Because the caribou were sparsely distributed to begin with, the herd simply cannot survive this increase in mortality. With so few mountain caribou left in the south Selkirk region and rapidly dwindling or extirpated northern caribou herds in the South Peace region, their future looks bleak.

My question is this. What is this government doing to ensure that the habitat for the remaining relatively healthy woodland caribou populations is protected in light of growing pressures from mining, natural gas and forestry sectors?

Answer

Hon. S. Thomson: As you know, the province has implemented mountain caribou recovery implementation plans. Oversight is provided on those plans by a progress board, a progress team, with a wide range of stakeholders and interests on those teams. They report out annually.

Since the plans were implemented or adopted, over 2.2 million hectares of habitat have been protected — 108,000 hectares in the south Selkirk area; 400,000 hectares in the Peace River.

We continue to work — with the input of scientists, biologists, the progress team — to monitor the implementation, to ensure that we continue to provide that habitat for this very, very important species here in British Columbia.

Supplementary Question

A. Weaver: My concern with this, of course, is that under the Species at Risk Act government must act to protect land when the caribou are threatened. My concern is for existing mountain herds that are not subject to species-at-risk legislation today because they are not threatened today.

You know, these protected lands also are incredibly important for biodiversity, especially in light of the ongoing global warming. I recognize that there are some in opposition who believe it’s not actually occurring despite overwhelming scientific evidence.

A lot of these protected areas for the existing caribou herds that are threatened are old-growth forests. They are only protected in light of the fact that they must protect them under the Species at Risk Act. My concern is this. Scientists will tell government that the south Selkirk herd will go extinct despite the government’s efforts. The government then no longer has to protect these forests under the species-at-risk legislation.

My question to the minister is this. Will the minister commit to the continued protection of these forests? Even if the caribou herds, those herds which required the forest to be protected in the first place under Canada’s Species at Risk Act…. Will they still be protected — because of the pressures that they will get from the forest industry for this valuable timber?

Answer

Hon. S. Thomson: Thank you for the supplementary question. Now 2.2 million hectares of land are protected under the implementation plans. As I said, we continue to work with the progress team to monitor that implementation, to report out annually on progress on the implementation plans.

As was mentioned, the herds are dispersed — 15 separate herds across British Columbia — so that why it’s important we continue to get the scientific and biologist advice in through the progress report and the range of stakeholders that are on the progress board report.

That’s why we’re also taking additional actions, particularly on the high-risk herds, to deal with what the member opposite talked about, imminent expiration of those herds. That’s why we’ve taken extraordinary steps in those specific herds to give the best chance that we can to ensure that we continue to protect and recover those herds. That’s where the focus of activity will continue to take place.

Video

Endangered Species Management: Caribou versus Wolves

Over the last few months British Columbia’s controversial wolf cull has been the subject of substantial public dialogue. Like most MLAs, I receive ongoing communication from numerous British Columbians questioning the rationale behind the government’s approach. These communications crescendoed when well known singer Miley Cyrus spoke out against the cull and urged her more than 23 million followers to sign a petition. One of the recent communications I received was from a young woman named Katie. She started off her email saying:

“My name is Katie, and I oppose the wolf cull. In school we learned about predator prey relationships. I know you probably won’t care, and that the government will go ahead with it anyway, but please read this…”

I found her email to be a source of inspiration. Despite her apparent cynicism towards politicians she took the trouble to express her concerns to me (even though she is not a constituent). Her email struck a chord. I campaigned on a promise of evidence-based decision-making and giving youth in our society, the generation that will have to live the consequences of the decisions my generation is making, a voice in the legislature. And so Claire Hume and I decided to look at BC’s controversial wolf cull a little more closely. What follows is an extensive analysis of the available literature. Our analysis derived from many hours of discussions with scientists, including wildlife biologists, with expertise in the area. I look forward to your comments.

Is it justifiable to kill one animal in the name of saving another? What if one of those animals is endangered?

Is it justifiable to kill one animal in the name of saving another? What if one of those animals is endangered?

I have always maintained that humans have a moral obligation to prevent endangered species from going extinct, but wildlife management conflicts in which species are pitted against one another are always challenging. For a variety of industrial, social, or budgeting excuses, they are often situations that have been allowed to escalate far past a point of simpler intervention. When you start rationalizing culling one species to protect another you also introduce an ethical element that needs to be considered alongside scientific findings. Let one – or both – of those species become threatened or endangered and your situation becomes immensely worse.

Many ecosystems have been altered so drastically that we can no longer let nature take its course. If we don’t continue to intervene with the mountain caribou crisis we are currently facing in B.C., for example, it will not be long before the remaining herds in the South Selkirk and Peace regions are extirpated. Ideally, our wildlife management system would never let things get this bad. But it happens. And when it does we have no choice but to make tough decisions.

In January I wrote to the Minister of Forests, Lands, and Natural Resource Operations to ask a number of questions regarding the rationale for the wolf cull in the South Selkirk Mountains and the South Peace region. In response Minister Thompson sent me the supporting data that backed up their wolf cull. I read through it and agreed that with 18 caribou left we needed to take immediate and drastic action to ensure as many caribou as possible survived through another breeding season. Since then, the issue has continued to polarize our province with both sides of the debate claiming science. And in many ways, both sides are right. There is supporting evidence that suggests, for certain situations, that culling wolves is an appropriate wildlife management tool. There are also many other studies that conclude that it is an ineffective solution, one that could make the situation even worse while causing a great deal of animal suffering in the process.

So, where do we go from here? We do a literature review of the available relevant research and we have a conversation. We explore the feasibility of other options and try to find a solution that maximizes protection for threatened species while minimizing the harm done to all other animals. Over the last few months my office has been talking to scientists and analyzing data across disciplines, across species, and across the country (across continents in one case) to learn more about endangered species management.

Lessons from the Vancouver Island Marmot

In the late 1990s the Vancouver Island marmot population dropped to 70 members. While clear-cut logging in marmot territory was thought to be the initial and main reason their population numbers were plummeting, the landscape changes also led to increased predation. Between 1995 and 2005 predation by wolves, cougars, and eagles accounted for 80% of marmot mortality. Much like the caribou, habitat destruction was the main catalyst for their decline and wolves moved in to take advantage of the new open landscape. I reviewed the group’s marmot recovery plan and contacted them to ask why predator control has never been a part of their strategy.

Their Executive Director, Viki Jackson, said they tried everything they could think of on Mount Washington in place of culling predators: they collared cougars and brought dogs in to scare them away, had “shepherds” stay with the marmot colonies, put dirty human clothes around to deter predators, put up fences, and used bear bangers. Having people camp with the marmots 24/7 worked well, Jackson said, but the other attempts didn’t do much. At the same time, they started to have success with their captive breeding program. Without their active intervention the Vancouver Island marmot would have likely gone extinct years ago.

When it comes to endangered species management, Jackson said, there will never be consensus but you have to do everything in your power to protect key females when animal numbers drop to extreme lows. You need to get them over the extinction hump and stable enough that other conservation efforts have a chance to help.

While the specifics of this case do not exactly translate to the needs of larger, transient animals like caribou, I found their imaginative approach to crisis species management inspiring. Threatened species in our province are facing very modern difficulties as they try adapt to new stressors and habitats changed by development. Perhaps we should be trying to combat these challenges with equally modern and innovative solutions before defaulting to predator culling, a practice that only targets one aspect of highly complex situations. With this thought I contacted Dr. Adam Ford from the University of Guelph’s Department of Integrative Biology to talk about the use of technology in wildlife research and management.

GPS Management

Global Positioning Systems (GPS) placed on collars, Dr. Adam Ford explained, can be used to pinpoint, with high accuracy, the location of an animal at a given time. It is also possible to track animals and process data almost instantaneously. Knopff and his colleagues, for example, used GPS to track cougar predation to study predator/prey interactions with immediate data retrieval. “Real time monitoring has enormous potential in the fields of wildlife ecology and conservation, especially for at-risk wildlife,” their report states.

With these systems you can monitor the spatial relationship between an animal and a wide variety of geographical features. Data can be collected that orients an animal in relation to specific points (like feeding grounds), linear features (roads, fence lines, fishing nets, etc.) and spatially dynamic features (like a mobile herd of livestock). Given these tracking advancements, and the incredible success scientist and conservation officers have had using them in wildlife management settings, it is hard not to feel hopeful imagining the great potential for their use with woodland caribou in BC. I think it would be worth assessing, for example, the feasibility of attaching GPS’ to select members of threatened caribou herds and their neighbouring wolf packs, as suggested by Dr. Ford. You could outfit caribou and wolves with GPS collars, Dr. Ford explained, and program them with a GSM-linked messaging system that warns managers when wolves, say, are within 1 km of the caribou. The managers could then travel to the coordinates shown in the GSM message, and herd the wolves away with aversive conditioning. That way, intervention is case-specific and the helicopter time is used much more efficiently. They use this method in Kenya with elephants to keep them away from crop fields and refer to it as ‘geofencing‘.

I appreciate comparing elephants to caribou sounds dangerously like an apples-to-oranges tangent, but the success the Save the Elephants organization has had with GPS-based wildlife management is incredible and certainly worth further consideration. Their Geo-fencing program started ten years ago, in the hopes of reducing human-elephant conflicts. “Kimani was the first elephant to be collared and tested under the Geofencing [system]. He became the focus of the Ol Pejeta management due to his considerable skill in breaking expensive fences. In December 2005 he went on a crop-raiding spree that lasted 21 straight nights.”

In phase one of the project they programmed a virtual fence line (or string of coordinates) into the GPS collar worn by the elephant. If the elephant strays out of his designated range – suggesting he is heading towards farms or villages – his collar sends a text message with his exact location to the reserve managers, who can then mobilize and intervene with negative reinforcements before he does too much damage. After only a few months in his GPS collar, Kimani the elephant had stopped breaking fences. Years later, Kimani has still not returned to his crop-stomping ways.

Another breakthrough, which does not relate to caribou but highlights the brilliant potential for innovative wildlife management strategies, was their elephants and bees hypothesis. “Having found that elephants run from the sound of bees, in 2007, we set up a unique beehive fence line in the area to see if they would deter elephants from raiding crops. To test our hypotheses, we geo-fenced several known crop-raiding elephants to see if their behaviour changed once confronted with large concentration of bees. Thanks to the geo-fencing technology, we were able to witness and confirm that bees did in fact deter elephants from crop raiding.”

Elephant-caribou differences aside, the technology is transferable. “The real-time monitoring algorithms presented here for monitoring African elephants (proximity, geo-fencing, movement rate, and immobility) are widely adaptable and applicable to monitor a variety of behaviours across numerous species,” wrote Wall et al.

While there is considerable consensus within the scientific community about the effective use of technology in wildlife management, I have found concerning disagreement about the role of wolves in caribou declines and the impact of culling them. What follows is a literature review of sorts, of the relevant research that has been done on this subject.

Wolf Cull Literature Review

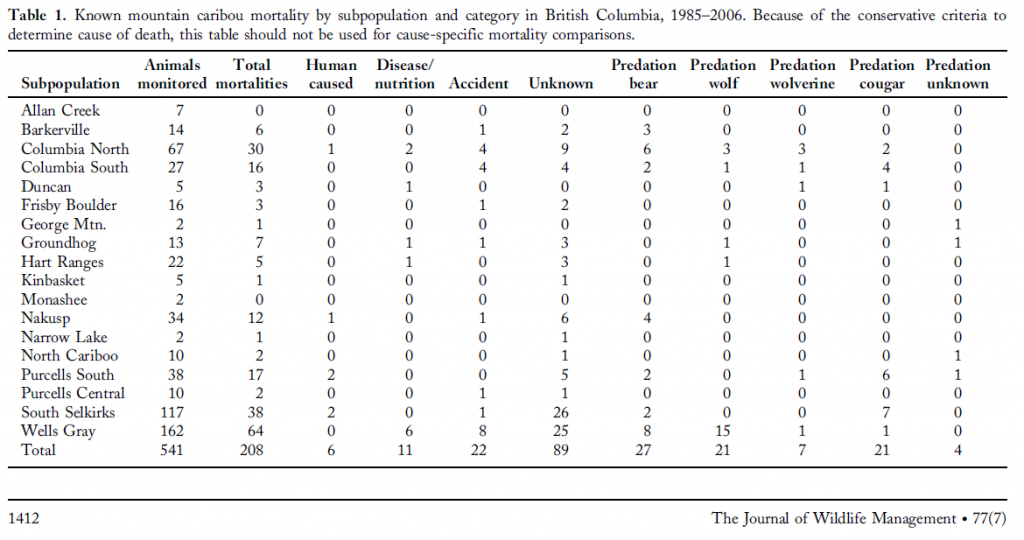

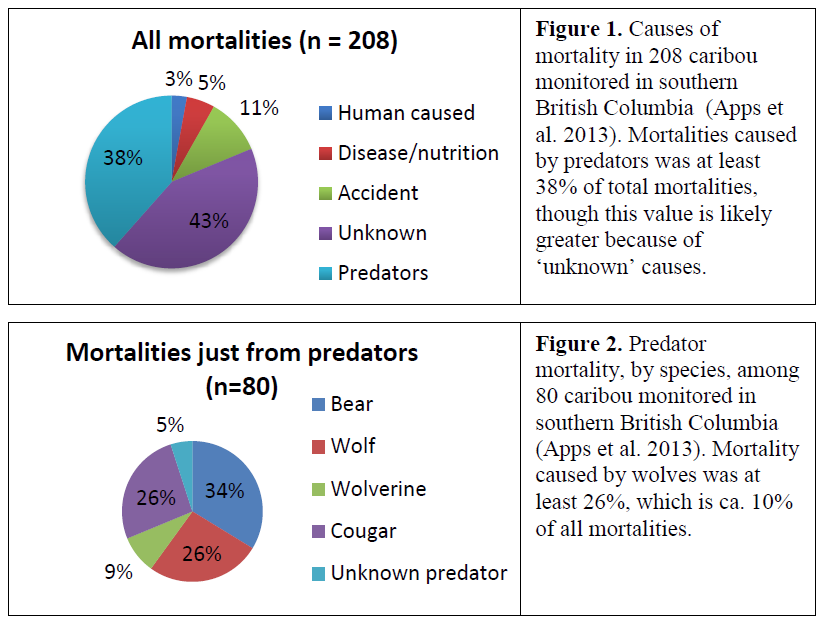

Apps et al. studied the GPS, very high frequency (VHF), and motion sensor data collected from 541 caribou over 22 years. When the collared animals stopped moving for prolonged periods researchers tracked their location and tried to determine the caribou’s cause of death. In their cause-specific mortality analysis of mountain caribou in B.C. they found that wolves are only one of many important sources of mortality for caribou. The data, though limited, indicates that wolves are not necessarily the primary killer of mountain caribou. In fact, it is possible that bears and cougars may have a stronger impact on caribou numbers. That said, I spoke to Dr. Clayton Apps about his study and he cautioned that the data should not generalized too broadly as it pertains to specific sampling cases. The wider conclusion of his work focused on caribou vulnerability as it relates to landscape changes. Wolf predation was found to be concentrated at lower elevations and areas with a higher concentration of roads, which they used as a navigational advantage when hunting.

On a similar theme, DeCesare’s data links industrial development with increased encounters between wolves and caribou, which in turn can lead to increased predation. Supporting that notion, other studies have illustrated the considerable impact wolves can have on local ungulate populations. Kortello et al. conducted a study that analyzed the diet and spatial overlap between wolves and cougars in Banff National Park. During their research they observed a 65% decline in local elk populations following the arrival of wolves. This shift caused cougars to switch from a primarily elk winter diet to one that favoured deer and other alternative prey options.

At this point we have a fairly clear picture of a wolf – caribou relationship that has been knocked out of whack in areas that have been altered by industrial development. Wolves eat caribou, even more so when roads and cleared forests give wolves efficient access to a larger range while simultaneously limiting caribou’s own food sources. If we have too few caribou, and too many wolves, it is easy to conclude a wolf cull would be an appropriate response. Some short term studies support that assumption. Bergerud et al. for example suggested that a wolf cull in Northern B.C. and the Yukon lead to increases in ungulate populations, but many studies do not.

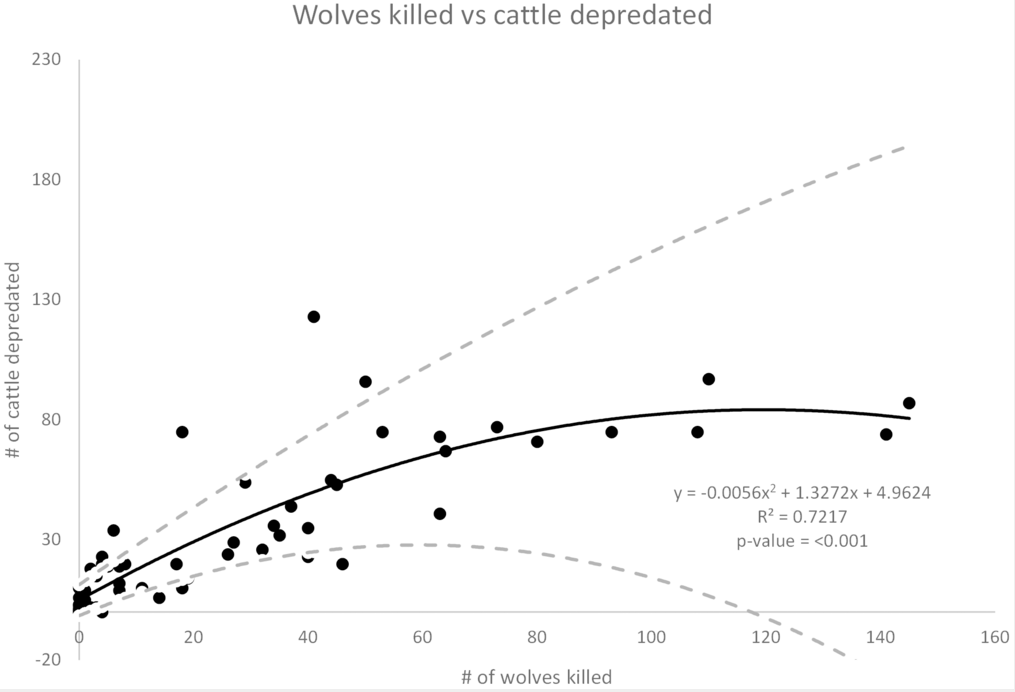

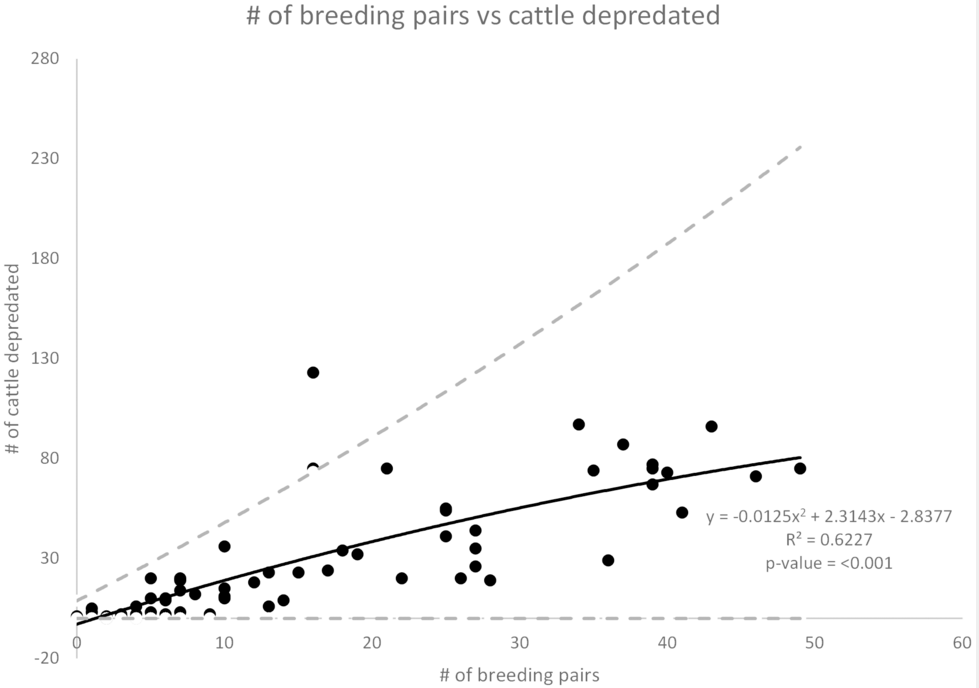

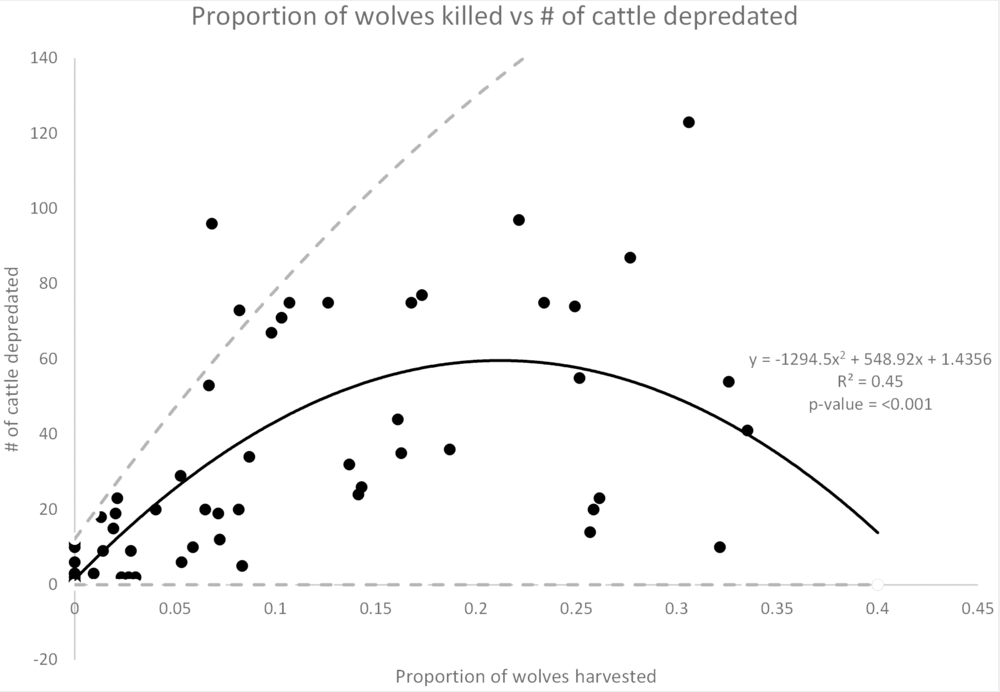

In an incredibly comprehensive and long term study, Wielgus et al. assessed the effects of a wolf cull on reducing livestock depredations in Idaho, Montana and Wyoming from 1987–2012 using a 25 year time series. The number of livestock depredated, livestock populations, wolf population estimates, number of breeding pairs, and wolves killed were calculated for the wolf-occupied area of each state for each year. Unsurprisingly, their results describe a positive association between the number of cattle in a given area, the number of cattle killed, and the number of breeding wolf pairs. In other words, as you increase the number of cows and wolves in a given area, instances of wolf-cow conflict will also rise. Incredibly, however, their data also shows a positive, not negative, association with the number of wolves culled the previous year – meaning culling wolves actually led to more livestock being killed by wolves the following year. “The odds of livestock depredations increased 4% for sheep and 5-6% for cattle with increased wolf control” (graphed in Figure 1.). Wielgus et al., hypothesized that livestock depredation increased when wolves were killed because the cull disrupted pack structures, which in turn, lead to a compensatory increase in breeding pairs, more pups, and more hunting (Figure 2.). This trend was consistent until 25% of the breeding wolf pairs had been culled, after which point livestock predations began to decline from its elevated state (graphed in Figure 3.). As the paper stresses, however, “mortality rates exceeding 25% are unsustainable over the long term.” As you can see in Figure 3., to get to the livestock mortality rate that you started with before the wolf cull elevated depredation levels, you would need to kill over 40% of the breeding wolf pairs. Ultimately, Wielgus et al. concluded that their results do not support the ‘remedial control’ hypothesis of predator mortality which predicts a drop in livestock following increased lethal control. “However,” they write, “lethal control of wolves appears to be related to increased depredation in a larger area the following year.”

Figure 1: Wolves killed versus cattle depredated: The number of wolves culled the previous year plotted against the number of cattle killed by wolves the following year. The black line indicates that as more wolves were killed through control methods, the remaining wolves killed an increased number of cattle. The dashed lines show the upper and lower limits of the 95% confidence interval for the best fit line.

Figure 2: Number of breeding wolf pairs versus cattle depredated: The number of breeding wolf pairs present in a region the previous year plotted against the number of cattle killed by wolves the following year. The black line indicates that as the number of breeding wolf pairs increases, so to does the number of cattle they kill. The dashed lines show the upper and lower limits of the 95% confidence interval for the best fit line.

Figure 3: The proportions of wolves killed versus cattle depredated: The proportion of wolves killed the previous year versus the number of cattle killed by wolves the following year. The black line indicates a 2-way negative interaction. Cattle depredation increased with increasing mortality up until roughly 25% of the wolf population was culled, then the number of cattle killed began to decline.

Echoing their conclusion from a different research angle, Brainerd et al. analyzed pooled data from 148 territorial breeding wolves and found increased movement and dispersal of wolves when the pack’s breeding (alpha) pair was removed. In other words, when you kill the alpha wolf pair who keep the rest of the pack in line, remaining wolves are statistically likely to breed more and spread into new territories. This disruption to the ecosystem is likely to trigger other changes and lead to issues to neighbouring environments.

Similarly, Treves et al. found that the removal of carnivores generally only achieves a temporary reduction in livestock depredation before other predators move in to fill their space and eat their prey. Harper et al. also found that killing a large number of wolves in Minnesota did not reduce the following year’s livestock depredation levels. They did notice, however, that a mere increase in human activity decreased the amount of hunting wolves did in the area.

Caribou Health

Credit: Mark Gocke, Wyoming Game and Fish

Unfortunately, there is yet another layer of concern to add to this complex analysis; caribou health. The University of Alberta’s Center for Conservation Biology began studying this issue after the government of Alberta announced plans to cull up to 80% of wolves in the oil sands in the hopes that it would slow the rate of caribou decline. They conducted dietary analyses had found that 60% of the caribou winter diet consisted of lichen. “This food source is particularly vital to pregnant caribou as it is high in glucose, which is the primary food source to the fetus,” they wrote. If female caribou do not have adequate access to lichen, they explained, it compromises their pregnancies and lowers birth rates.

“They [the government of Alberta] argue that climate change and habitat disturbance are causing deer, the preferred prey of wolves, to move north into the oil sands. Wolves are said to increase in response, increasing the risk of predation on caribou. Our work suggests that there may be better options.”

The conservation biologists suggested that reducing human and industrial activities in lichen rich feeding grounds may be a more effective mitigation strategy than killing wolves.

“Moreover,” they continued, “owing to the preference of wolves for deer, removing wolves from the population to protect caribou could actually place the ecosystem at markedly greater risk by accelerating the expansion of deer into this ecosystem.”

The Columbia Mountains Institute of Applied Ecology has picked up on this theme too. “Caribou decline may be related to too much energy spent on just trying to stay alive,” explained national park warden John Flaa. “Over the past summer, the three caribou mortalities I investigated had no body fat, which is bound to have an effect on calf production. Census results here show that the proportion of calves in the herd are below replacement level.”

Accessing an adequate food supply has been an ongoing issue for elk too, especially across the border in Wyoming. Their Game and Fish Wildlife Division, however, has managed to greatly inflate herd size over the last few decades by feeding them hay every winter. Not surprisingly, issues of disease began to increase as more elk congregated at feeding grounds. As Creech et al. explained; “High seroprevalance for Brucella abortus among elk on Wyoming feedgrounds suggests that supplemental feeding may influence parasite transmission and disease dynamics by altering the rate at which elk contact infectious materials in their environment.” Thankfully, they have also since shown that spreading out feeding areas reduces cross contamination infection rates by 70%.

This is not an ideal solution, of course, but it has been quite successful in many respects. Elk populations in Wyoming are now strong enough to support hunting, an activity that more than covers the cost of the feeding program. “Elk hunters spent $49.9 million in 2012… The program cost $558 per animal and generated $1,856 in ‘economic return’ per [elk].”

Conclusion

As Dr. Adam Ford wrote in his summary paper Science, Uncertainty, and Ethics in the Alberta Wolf Cull; “It is past time that we adopt a more creative view of how we can coexist with caribou and wolves in an industrialized landscape.” After reviewing the literature available on this and related issues I agree. While this is an undeniably complex situation with a lot at stake, I think we should be doing more to learn from innovative wildlife managers around the world.

We could try creating a geo-fence between wolves and threatened caribou like conservation officers do with their problem elephants in Kenya. Or get ‘caribou shepherds’ to track GPS collared herds, intervening when they are at risk of predation; much like the ‘marmot shepherds’ who saved endangered (admittedly easier to track) colonies on Vancouver Island. We could explore the feasibility of capturing, sterilizing, and re-releasing the alpha breeding pair in a pack of wolves; thereby reducing the growth of a wolf population while keeping the governing pack structure in place. Given the above concerns about food availability for caribou, as well as the effective use of feed lots elsewhere, I think we should also consider supplementing the diets of the South Selkirk and Peace region herds with a stable supply of lichen over the winter. It would be a relatively cost effective, simple, and could potentially be game-changing for our struggling caribou.

Some of these solutions may sound crazy, but when you consider we are currently spending millions of dollars to indiscriminately shoot wolves from helicopters, I would argue they potentially offer for more cheaper and less-crazy alternatives.

Acknowlegements

We are sincerely grateful to the many scientists who made time to talk to us about their work.

The Wonders of Nature Research Day

Today I was afforded the honour of delivering the opening the opening remarks at the Wonders of Nature Research Day put on by UVic’s Centre for Early Childhood Research and Policy. The research days featured presentations by a number of distinguished scholars including:

- David Sobel, Department of Education, Antioch University, New England

- Michael Marker, Department of Educational Studies, University of British Columbia

- Sean Blenkinsop, Faculty of Education, Simon Fraser University

- Ulrich Mueller, Department of Psychology, University of Victoria

- Viv Temple, School of Exercise Science, Physical and Health Education, University of Victoria

- Enid Elliott, School of Health and Human Services, University of Victoria

Below is the text of my opening remarks.

Text of Opening Remarks

I would like to start off by thanking Beverley and everyone at the Centre for Early Childhood Research and Policy for inviting me here today and for organizing this wonderful conference. As Beverley pointed out, my name is Andrew Weaver and I’m the Member of the Legislative Assembly representing the riding of Oak Bay-Gordon Head — home to the University of Victoria.

I would like to start off by thanking Beverley and everyone at the Centre for Early Childhood Research and Policy for inviting me here today and for organizing this wonderful conference. As Beverley pointed out, my name is Andrew Weaver and I’m the Member of the Legislative Assembly representing the riding of Oak Bay-Gordon Head — home to the University of Victoria.

I have been in the Legislature for about two and a half years now, but before that I actually worked right here at UVic as a Faculty Member in the School of Earth and Ocean Sciences. In parallel with my endeavours in research, I’ve spent a good deal of time engaging the public in discussions about the importance of nature and our environment, and the detrimental path we are headed down if we don’t take action to reduce ongoing loading of the atmosphere with greenhouse gases that are causing global warming.

While it is easy to become disillusioned and worn out working in the field of climate science — seeing the path we’re headed down and fighting an uphill battle to try and make governments and policy makers see it too — it is our children and youth that inspire me — give me hope for the future — and keep me optimistic after so many years in this field.

In fact, one of my favourite parts about my role as MLA, is being able to go into schools and universities and speak to children and youth about our environment and the importance of civic engagement. Seeing their keen interest and appreciation for our natural environment and their desire to make our world a sustainable place is truly what inspires me in my daily work down in the legislature.

Because of this, I was very honoured when I was asked to provide opening remarks here today — I’m just disappointed I won’t be able to stick around to learn about the fantastic research that is being done in this area.

I was actually fortunate enough to experience a nature school program first-hand about a year and a half ago. I was invited by Savory Elementary School to be an “Eco Expert” for their “4 Seasons Eco School”. The program, which I believe was in its inaugural year when I visited, ran each Wednesday and provided all students with the opportunity to learn outside in Savory’s surrounding ecosystem, bringing in a new guest expert each week to guide the children.

I got to spend an entire day, from 8:30 in the morning to 2:30 in the afternoon, delivering a lesson plan to seven separate classes and engaging with every grade from Kindergarten to grade 6. To say that I was exhausted by the end of it would be an understatement, but it was also a truly unforgettable and inspiring experience — and helped to further my respect and appreciation for our teachers who do far more than I did, but on a daily basis.

Over the last decade as a scientist I’ve also had the privilege of working with school districts across Vancouver Island to install more than 150 weather stations on schools (Islandweather.ca for those who are interested), and to develop learning resources, in collaboration with teachers, to allow them to deliver their curriculum using state-of the art instrumentation and an authentic learning experience. Getting out of the ivory tower and into the community to discuss science, weather and our natural environment has been — to be perfectly frank — the single most satisfying and rewarding experience I have had as a scientist.

In today’s technology driven world, where young children are spending as much as eight hours a day interacting with screens — and often less than an hour a day actually outside – I firmly believe that providing children with the opportunity to experience “the wonders of nature” is one of the most important things we can do to help foster their development. While I am by no means an expert in the topic — you will hear from them later — I do know that there is a vast amount of research to demonstrate just how important time spent outdoors is to early development. Studies have shown that children who interact with nature on a daily basis are healthier, happier, more creative and less stressed than those who don’t.

And these benefits are not only felt in childhood. Researchers continue to develop a better understanding of the lasting impacts that early childhood experiences can have on our lives. Whether we remember the experience or not, and whether we are aware of magnitude of those experiences or not, they can stick with us throughout our entire lives. We carry them with us through our adolescent and teen years, into young adulthood and beyond. Developing an understanding and appreciation of nature at an early age will have a lasting effect on children.

And these benefits will not just be felt by the children fortunate enough to experience this type of learning environment. They will be felt by their peers, their families, their communities, and society as a whole. They will impact the way they interact with other people, the way that they view and interact with their environments — both built and natural, and the way that they engage in their future careers.

In a few decades, the children that we’re talking about today will be our teachers, our researchers, our scientists, our policy makers, and our government leaders. They will be making the decisions that influence our society, implementing the policies that protect our environment, and educating an entire future generation of children on the importance of our natural world. So the fact that you are all here today, discussing such an important initiative, is a truly inspiring sight to see!

Thank you again for having me here to speak today and enjoy the rest of the conference!

Debating a Motion on the Merits of Site C

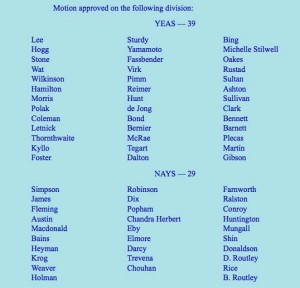

Today in the Legislature, we debated the merits of the Site C project. The motion brought forward for debate by Bill Bennett, the Minister of Energy and Mines, was as follows:

Be it resolved that this House supports the construction of the Site C Clean Energy Project; because the Site C Clean Energy Project represents the most affordable way to generate 1,100 megawatts of clean and reliable power; and the Site C Clean Energy Project will create jobs for thousands of British Columbians; and the Site C Clean Energy Project has been the subject of a thorough environmental review process.

I’ve written extensively on this topic over the years and so spoke strongly against the motion. Please consider reading my rationale for taking this position.

Text of my Speech

On April the 19th of 2010, I, along with numerous others, travelled to Hudson’s Hope to hear then Premier Gordon Campbell announce the Site C project was moving to the environmental assessment stage. A lot has changed since 2010, and the environmental assessment has now been completed.

The joint review panel’s report published on May 8th, 2014, identified major obstacles in the path for approval. While the report did not emphatically say yes or no to the project, certain sections highlighted the permanent damage to the environment, farmland and wildlife the project would have. These included effects on First Nation rights and lack of exploration of similar cost renewable energy alternatives.

I’ve been pointing out for several years now that Site C is the wrong project at the wrong time when alternative energy, including geothermal, wind, tidal and small-scale hydro sources, coupled with existing dams would provide substantially improved firm energy and capacity. This approach would be less damaging to the environment and distributed around British Columbia. It would provide future power requirements with better costs and employment opportunities. Geothermal, wind, tidal and smaller hydro projects would deal substantial economic benefit to communities, especially First Nations.

The joint review panel specifically concluded the following.

On the environment and wildlife:

(1) “the project would cause significant adverse effects on fish and fish habitat”;

(2) “significant adverse effects on wetlands, valley bottom wetlands”;

(3) “the project would likely cause significant adverse effects to migratory birds relying on valley bottom habitat during their life cycle, and these losses would be permanent and cannot be mitigated”.

On the topic of renewables:

They said this:

“The scale of the project means that if built on B.C. Hydro’s timetable, substantial financial losses would accrue for several years, accentuating the intergenerational pay-now, benefit-later effect. Energy conservation and end-user efficiencies have not been pressed as hard as possible in B.C. Hydro’s analyses. There are alternative sources of power available at similar or somewhat higher costs, notably geothermal power. These sources, being individually smaller than Site C, would allow supply to better follow demand, obviating most of the early year losses of Site C. Beyond that, the policy constraints that the B.C. government has imposed on B.C. Hydro have made some other alternatives unavailable.”

Regarding First Nations:

The panel said this.

(1) The panel “concludes that the project would likely cause a significant adverse effect on fishing opportunities and practices for the First Nations represented by Treaty 8 Tribal Association, Saulteau First Nations and Blueberry First Nations and that these effects cannot be mitigated”;

(2) the panel “concludes that the project would likely cause a significant adverse effect on hunting and non-tenured trapping represented by the Treaty 8 Tribal Association and Saulteau First Nations and that these effects cannot be mitigated”;

(3) “the project would likely cause a significant adverse effect on other traditional uses of the land for the First Nations represented by Treaty 8 Tribal Association and that some of the effects cannot be mitigated”;

(4) “the project would likely cause significant adverse cumulative effects on current use of lands and resources for traditional purposes”.

In 2010, the projected construction costs for the dam was $6.6 billion. But by May of 2011, that cost had increased to $7 9 billion — a 20 percent increase. By 2014, it rose a further 11 percent to $8.8 billion.

Now, there’s considerable upside uncertainty regarding these costs that could easily reach $10 billion, $12 billion, $15 billion or even more frankly. Just yesterday, we found out that more delays and cost overruns are occurring in Nalcor Energy’s Muskrat Falls hydro project in Labrador.

Nalcor Energy’s CEO, Ed Martin, cited three reasons for the cost overruns.

- he said: “It’s a tough, tight marketplace right now.”

- he said: “What we’re seeing in these bids when they come in is they’re higher, much higher, than we have budgeted for.”

- he said: “What we’re doing is experiencing cost increases we really can’t control in that area.”

Now, I have little confidence in the cost forecasts for the construction of Site C, as it won’t be completed for many, many years. I share the desire of the government to see British Columbia’s economy managed in a way that ensures a sustainable approach that is not burdening future generations with the cost of decisions we make today.

In the past, our government has, appropriately, celebrated the fact that British Columbia has maintained a triple-A credit rating. Having the taxpayer take on an almost $9 billion-and-growing debt to subsidize this government’s efforts to chase the pot of gold at the end of the LNG rainbow strikes me as profoundly irresponsible for the supposedly fiscally conservative B.C. Liberals. Risking a potential downgrade of our triple-A credit rating would risk raising the costs of servicing all of our provincial debt.

Now, I recognize that as the population grows and the economy in British Columbia also grows, so too does our need for energy. But the Site C project has grown increasingly indefensible from a social, environmental and economic standpoint. This proves especially true when weighed against more practical alternatives.

The impacts of the project are widespread. Thousands of acres of farmland and wilderness will be flooded, doing irreparable damage to ecosystems. The hunting and fishing and traditions of First Nations who live in and around these lands will be threatened. Billions of dollars will be spent on the project, raising concerns over British Columbia’s economic viability and triple-A credit rating. All of these staggering realities might be forgiven if Site C was the only realistic solution. It’s not, and I’m not the only one who realizes this.

There are many alternatives that are cheaper to build and maintain, have minimal environmental footprints and generate more permanent jobs that are spread throughout the province. Chief among these options are wind and geothermal power.

The claim that Site C dam is the most affordable way to generate power is absolutely untrue. Recently for example, the Peace Valley Landowner Association commissioned an independent report from the U.S. energy economists Robert McCullough to look at the business case for what could become the province’s most expensive public infrastructure project ever.

According to Mr. McCullough: “Using industry standard assumptions, Site C is more than three times as costly as the least expensive option. Thus, while the cost and choice of potions deserve further analysis, the simple conclusion is that Site C is more expensive than the renewable and natural gas portfolios elsewhere in the U.S. and Canada.”

Mr. McCullough’s assertion that B.C. Hydro had its thumbs on the scale, so to speak, in an effort to make the Site C project look better than private sector alternatives appears, frankly, correct. In his report, he notes the following. Provincial accounting changes adopted in 2014 “to reduce the cost of power generated” are illusory. The costs will, like all costs, have to be paid, whether by hydro ratepayers or provincial taxpayers.

Mr. McCullough also disputes the rate that B.C. Hydro used to compare the long-term borrowing costs of capital for Site C against other projects. This so-called discount rate being proposed by B.C. Hydro is critical to overall cost projections, yet despite this, the paper trail on the discount figure — I quote Mr. McCullough — “could only be described as sketchy and inadequate,” especially when other major utilities in North America use higher rates for such projects because they are considered risky investments.

Mr. McCullough outlines major economic risks for the province in his report, assertions that are further solidified by Harry Swain, the chair of the joint federal-provincial panel that reviewed the Site C dam.

In recent years, as part of the Columbia River treaty, B.C. has been selling off the Canadian entitlement of our electricity to the tune of $100 million to $300 million annually. From 2010 to 2012, that translated to $30 per megawatt hour. But in the meantime, the cost of power from the Site C dam is estimated at $83 per megawatt hour.

How does it make sense to be building new sources of power at $83 per megawatt hour while continuing to export power for $25 to $40 per megawatt hour? Swain’s report predicts that as a result of B.C. Hydro generating more power than the province actually needs, the Site C dam would lose at least $800 million in the first four years of production.

The Site C dam is not a small project. Construction will require the province to borrow nearly $9 billion, and growing, and yet the project has been exempted from an independent regulatory review by the B.C. Utilities Commission.

What kind of message does this send to the citizens of this province about the government’s commitment to accountability and transparency? Why, when two independent reviews of the project have dismantled the claim that the site project is the most affordable way to generate power, do B.C. Hydro estimates claim otherwise? Why does the province refuse to sponsor its own independent regulator’s review of the project?

The only possible answer is that B.C. Hydro figures are totally illusory, manipulated to fit the government’s political guarantee of “endless investment” in the province.

Associated with the announcement on December 16 of last year that the B.C. government was going to proceed with the construction of Site C was some very creative accounting, designed to make Site C look more competitive than it really was. The government claimed that they found savings, while the overall project costs actually rose. I’m not making this stuff up. All the government had actually done was move the financial costs of this megaproject into a different category. The fact is that the costs had gone up and so had the burden on taxpayers.

The updated cost of Site C on ratepayers was reduced from $83 per megawatt hour to $58 to $61 per megawatt hour, with the majority of the change coming from a commitment from government to take fewer dividends from B.C. Hydro. However, this merely shifted the capital cost of building the dam from B.C. Hydro ratepayers to British Columbia taxpayers.

Just three weeks earlier, on November 25, I attended a Canadian Geothermal Energy Association — known as CanGEA — press conference, where they released a report entitled the following: Geothermal Energy: The Renewable and Cost Effective Alternative to Site C.

Some of the key findings in that report included the following:

- Geothermal energy unit cost, conservatively, was estimated at $73 per megawatt hour, compared to B.C. Hydro’s $83 per megawatt hour for Site C, a number that was, as I pointed out, creatively reduced to $58 to $61 per megawatt hour shortly after this press conference;

- Geothermal plant construction equaling the energy output of the proposed Peace River dam is estimated at $3.3 billion compared to at least $7.9 billion for Site C, raising to $8.8 billion just three weeks later;

- Geothermal plants provide more permanent jobs that are distributed across British Columbia — another key finding in the report;

- For the same power production, the total physical and environmental footprint of geothermal projects would be substantially smaller than Site C.

We are the only jurisdiction in the Pacific Rim that does not have any geothermal capacity in our province, state or territory. British Columbia has a significant potential to develop geothermal and other renewable energy projects throughout the province. Such projects would distribute energy production where it is required and allow power to be brought on line as demand increases.

The available evidence at that time made it clear that the government should not proceed with the Site C project. There were simply too many cheaper alternatives available to protect the ratepayer or the taxpayer. The clean energy sector was eagerly awaiting a more fiscally responsible investment decision that would provide employment and development opportunities across the province.

Site C was then, and still remains, the wrong project at the wrong time. Alternative energy, including geothermal, wind, solar, small-scale hydro sources and biomass, coupled with existing dams, would provide firm energy and capacity at a better cost to British Columbians. They would also provide better economic opportunities to local communities and First Nations, with lower impacts on traditional territory.

In March of this year, Harry Swain, co-chair of the joint review panel appointed for the Site C dam and former deputy minister of Industry Canada and of Indian and Northern Affairs, raised some very serious concerns about the government’s approach to approving Site C. Mr. Swain was very clear that the government was rushed in approving Site C and that British Columbians will pay for their haste.

As Mr. Swain said: “Wisdom would have been waiting for two, three, four years to see whether the projections they” — that’s B.C. Hydro — “were making had any basis in fact.” That’s not exactly a glowing endorsement for the fiscal underpinning of Site C. The review panel predicted that by building it now, Site C will actually produce more electricity than we’ll need for the first four years, costing taxpayers $800 million.

Mr. Swain isn’t the only person to suggest waiting a few years to see if electricity demand for the project materializes. We could still build Site C down the road if necessary, but we could use the additional time to properly explore cheaper alternatives, like our vast geothermal potential in B.C. We have the time, and as I mentioned earlier, that pot of gold at the end of the LNG rainbow won’t be found any time soon, if ever at all.

Mr. Swain went even further. He argued that pushing Site C through without adequate consideration of cost-effective alternatives was a “dereliction of duty.” Those are strong words — “dereliction of duty” — from a very highly regarded senior official from the Canadian government, a very distinguished scholar, a very distinguished senior official, and the chair of the joint review panel. I repeat: “dereliction of duty.”

To be even more blunt, it’s recklessness on the part of the government. We have a sense of the cost: an $800 million loss in the first four years of operation, because of the construction timing. We know there are affordable alternatives to Site C. These alternatives would allow us to meet present and future energy needs without running the risk of incurring increased public debt and potentially damaging our Triple-A credit rating.

The fact is that circumstances have changed since 2010. That’s why I no longer believe it’s fiscally prudent to move forward with this project. In the last few years, the cost of wind energy and solar PV have dropped dramatically. China, for example, is building a new windmill every hour, and China’s investment in photovoltaics has led to an 80 percent drop in price in just five years.

Over the next 20 years, B.C. Hydro has forecasted that our energy needs will increase by about 40 percent as a consequence of population and economic growth. Upon completion, this dam would produce 1,100 megawatts of power capacity and up to 5,100 gigawatt hours of electricity each year. According to B.C. Hydro, this is enough electricity to power about 450,000 homes.

So let’s look at wind power. Recently a study was produced by the investment banking firm Lazard, which suggested that the cost of unsubsidized utility-scale wind could be produced as low as $19 per megawatt hour. I repeat that the cost of unsubsidized utility-scale wind could be produced as low as $19 per megawatt hour, about a quarter of the proposed costs of the Site C dam initially and still substantially less than the revised proposed costs.

Currently in B.C., only 1.5 percent of electricity production is supplied by wind energy — incredibly low when compared with other jurisdictions internationally. But with British Columbia’s mountainous terrain and coastal boundary, the potential for onshore and offshore wind power production is enormous, almost unparalleled internationally.

The Canadian Wind Energy Association and the B.C. Hydro integrated resource plan 2013 indicate that 5,100 gigawatt hours of wind-generated electricity could be produced in British Columbia for about the same price as the electricity to be produced by the Site C dam.

That is before the price of wind dropped substantially further since 2013, and is despite the fact that all costs, including land acquisition costs incurred to date by B.C. Hydro with respect to the Site C project, have never been counted in their estimate for future construction costs. The potential scalability of Site C is minimal to nonexistent. The potential scalability of wind energy is boundless.

The minimal production of wind power in British Columbia compared to other jurisdictions around the world is surprising in light of the fact that B.C. is the home of a number of existing large-scale hydro projects.

What do I mean by that? These projects include but are not limited to the W.A.C. Bennett and Peace Canyon dams already on the Peace River and the Mica, Duncan, Keenleyside, Revelstoke and Seven Mile dams on the Columbia River system.

Hydro reservoirs are ideally suited for coupling with wind power generation to stabilize baseload supply. It’s really quite simple. When the wind is blowing, use the wind energy. When the wind is not blowing, use the hydro power. That is, hydro power, coupled with wind, acts like a rechargeable battery, with wind being the recharger and the dam being the battery.

British Columbia is one of the few jurisdictions in the world, if not the only, that has the potential to take advantage of such reservoirs as wind power, if wind power were to be introduced to the grid.

Denmark, the world’s largest producer, does not have that power. Britain — a jurisdiction where, just recently, renewable energy producers started to produce more than half of its power — does not have the reservoir capacity. But British Columbia has it all, and we’re wasting an opportunity.

Given that wind power can so easily be introduced into B.C. at an even lower price than equivalent power from Site C dam, we should ask if there are other reasons that would favour Site C over wind for the production of power to meet B.C.’s present and future energy needs.

Frankly, I can think of none. In fact, I can think of a number of reasons why wind power should be considered over Site C to produce the equivalent of 5,100 gigawatt hours per year of electrical power. Let me summarize these:

1) The construction of Site C dam will flood 6,427 acres of class 1 and 2 agricultural land and a total of 15,985 acres of class 1 to 7 agriculture land. Wind power sites would not affect agricultural land. In fact, the Peace River Valley contains the only class 1 agricultural land north of Quesnel.

2) Key regions in the archive of British Columbia’s history will be flooded. It’s unknown how many unmarked First Nation graves lie in the flood zone. But the Globe and Mail recently reported it could be in the thousands. B.C. Hydro’s own archaeological research in the valley turned up everything from dinosaur teeth to ancient stone tools and old fur-trading posts. In all, it identified 173 paleontological sites, 251 archaeological sites and 42 historic sites. The Peace River has been designated as a B.C. heritage river. It was, in fact, traversed by the explorers Alexander Mackenzie, John Finlay, Simon Fraser, John Stuart, A.R. McLeod and David Thompson, among others, in their early ventures during the 17th and 18th century. Rocky Mountain Fort, thought to be the first trading post established in British Columbia by John Finlay in 1794, as well as Rocky Mountain Portage House, across the river from Hudson’s Hope and established by John Finlay and Simon Fraser in 1805, are both located in the valley that will be flooded. The joint review panel determined that the loss of the cultural places, as a result of inundation, for aboriginal and non-aboriginal people to be of a high magnitude and permanent duration and to be frankly irreversible. The existing historically valued cultural sites would be permanently lost.

3) Job creation associated with wind, solar and geothermal power, for example, is provincewide, not in one region. Job region associated with the Site C dam is only in and around the Peace River Valley. Wind, geothermal, etc. provides distributed jobs, stable jobs across our province.

4) the risks of cost overruns associated with the construction of the Site C dam is borne by the taxpayer. The risks of cost overruns associated with the construction of wind, solar and geothermal facilities is borne by industry. This is important as it limits any risk to the taxpayer.

5) the installation of wind and other renewable energy projects can be done in partnership with First Nations, who would benefit from both local jobs as well as of revenue from the installed facilities. In contrast, the affected Treaty 8 Tribal Association has already expressed a number of serious concerns regarding the Site C dam proposal.

6) it would take longer to complete the Site C dam project than it would to install wind farms, for example. In addition, wind power is scalable, whereas Site C dam is not.

7) wind farms and other sources of renewable energy are distributed and so can be located close to where the energy is actually needed, thereby reducing transmission loss, energy loss, as electricity is transported long distances through power lines.

I recognize that B.C. Hydro operating under the Clean Energy Act has no other option in their mandate to build anything other than dams. In my view, the government has one of two choices to protect the rate and taxpayers from the unnecessary costs of the Site C construction.

First, they could either change the mandate of B.C. Hydro to allow it to invest in alternate energy technologies. Or, the second, they could require B.C. Hydro to issue calls for power to see how the market will respond. Either of these choices are acceptable and would allow the generation of other sources of power in British Columbia.

I also realize that the only reason why the Site C is going ahead now is because of the fact that on November 4, 2014, B.C. Hydro signed an agreement with LNG Canada to provide long-term power that we don’t actually have at $83.02 per megawatt hour.

But at what cost? We’ve already embodied a generational sellout in the amended LNG Income Tax Act. And that was taken to an even more egregious level in this past July’s Liquefied Natural Gas Project Agreements Act.

Now again — and just a side bar and based on the evidence today of Bill 34 being brought forward to discuss — it is precisely clear to me that there was no need at all for a summer session, as this government is so void of new ideas that we’re having to name a date in March as a day to celebrate red-tape reduction.

Now yet again, the taxpayer will step up to subsidize the government’s irresponsible quest for the mythical pot of gold somewhere at the end of the LNG rainbow. But at what cost? The building of Site C will decimate the clean tech sector that is at a critical phase in its development in B.C. and at a phase that actually employs more British Columbians today than does the oil and gas sector.

But at what cost? EDP Renewables, an internationally-acclaimed clean energy company, First Nations and TimberWest have walked away from a $1 billion wind energy investment on Vancouver Island. That’s not hypothetical. That’s here today. That’s gone today because of the irresponsible decisions being made in this government with respect to Site C and its LNG pipe dream.

For what? A desperate attempt to fulfill a suite of irresponsible election promises made in the run-up to the 2013 election. A 100,000 jobs; $100 billion prosperity fund; $1 trillion increase to our debt; Debt-free B.C.; elimination of PST; thriving schools and hospitals; and everything else in nirvana that is to be B.C.

As I’ve been pointing out for three years now, these promises were never grounded in an economic reality three years ago. They are not grounded in economic reality today. Nor will they be grounded in any economic reality in the foreseeable future.

Frankly, the incompetence of our government’s bumbling attempts to land LNG final investment decisions have made the British Columbia government a laughing stock on the international energy scene. The lack of a fiscally conservative approach to energy policy in this province makes me wonder just what this government is thinking. They are chasing a falling stock and doubling down in the process.

Sadly, the province will have to wait until 2016 or early 2017 before the B.C. Green Party brings forth our integrated platform. We will offer British Columbians an innovative vision for an integrated energy policy. We’ll offer British Columbians a plan to grow our resource-based economy and communities, and we’ll always put the interest of British Columbians first, not vested interest or political ambitions. They will be first and foremost in our policy formulation.

Site C is fiscally foolish, socially irresponsible and environmentally unsound. It no longer represents a wise economic social environmental option for providing British Columbians with the power they need. There are other alternatives available at cheaper costs with lower environmental and social impacts.

This motion must fail.