Justice

Standing up for Resident Hunters over Foreign Trophy Hunters

Today in the legislature I introduced Bill M234 — Wildlife Amendment Act, 2017.

This bill combined two previous bills that I had introduced in the legislature. The BC Liberals did not wish to bring either of these to second reading. The first Bill was to designed to reduce the preferential treatment of non-resident hunters by eliminating the minister’s discretion to make separate rules for resident and foreign hunters when it comes to obtaining LEH permits. This bill requires all hunters to enter a lottery for their LEH tags, as is done in other jurisdictions.

The second Bill I had already introduced was designed to ensure that all edible portions of animals hunted in British Columbia are taken to the hunter’s domicile. In addition, the proposed changes remove grizzly bears from the list of animals exempt from meat harvesting regulations. These put in place a major logistical barrier to foreign trophy hunting.

Two new additions were included in the updated bill. I am grateful to the feedback I received on my earlier bills that led to these modifications. First, if passed this bill would require that edible portions be packed out prior to, or in conjuction with, any other body parts of the game carcass. This is consistent with the notion is that hunting is primarily for food and the the trophy should be viewed as a by-catch.

The second addition would disallow those convicted of fisheries or wildlife offences from becoming fishing or hunting guides in the province of British Columbia.

Below I reproduce the text and video on my introduction along with the accompanying press release .

Text of the Introduction

A. Weaver: I move that a bill intituled Wildlife Amendment Act, 2017, of which notice has been given in my name on the order paper, be read a first time now.

Motion approved.

A. Weaver: It gives me great pleasure to introduce this bill that, if enacted, would make a number of changes to the Wildlife Act.

This bill restricts the practices of non-resident trophy hunters who come to B.C. to kill large game by making three specific amendments to the Wildlife Act. The proposed changes remove grizzly bears from the list of animals exempt from meat harvesting regulations, ensures all edible portions of animals killed in B.C. are taken directly to a hunter’s residence, and requires the meat to be taken out first, before the hide or head.

This bill also stops government from letting non-resident hunters buy preferential access to limited-entry hunting permits and bans people convicted of fisheries or wildlife offences from becoming fishing or hunting guides in the province of British Columbia.

For local sustenance hunters, the vast majority of hunters in B.C. that is, this bill merely echoes what they are already doing — harvesting wild game to bring the meat home to feed their families. For non-resident trophy hunters coming to B.C. to hunt an animal only for its hide, skull or antler, this bill puts in place a significant logistical challenge.

Bill M234, Wildlife Amendment Act, 2017, introduced and read a first time.

A. Weaver: At this time, I move, pursuant to standing order 78a, that this bill be referred to the Select Standing Committee on Parliamentary Reform, Ethical Conduct, Standing Orders and Private Bills for immediate review.

Madame Speaker: I will point out that that’s a departure in practice.

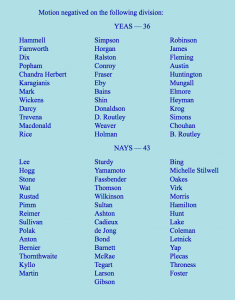

All those in favour? Nay is heard. Division has been called.

A. Weaver: May I have this referred to second reading — a motion to do so?

A. Weaver: May I have this referred to second reading — a motion to do so?

Bill M234, Wildlife Amendment Act, ordered to be placed on orders of the day for second reading at the next sitting of the House after today.

Video of the Introduction

Media Release

Weaver tables Wildlife Amendment Act to Committee Stage – Liberals vote Nay

For immediate release

March 6th, 2017

VICTORIA B.C. – Today in the legislature MLA Andrew Weaver tabled the Wildlife Amendment Act directly to committee stage, leading to an immediate vote in the House. Weaver and the B.C. NDP voted in favour of moving the bill directly to committee stage for review. The B.C. Liberals voted against it.

“This bill works to ensure that sustainable, respectful sustenance hunting in British Columbia is grounded in a science-based conservation policy and that the interests of residents hunters are put ahead of foreign trophy hunters.

“It is clear these are values the B.C. Liberals do not share – as illustrated by their vote against further consulting on this bill today. But, I am glad to see that the B.C. NDP support my initiatives on this file,” says Weaver.

The bill would restrict the practices of non-resident trophy hunters who come to B.C. to hunt large game by making three specific amendments to the Wildlife Act. The proposed changes remove grizzly bears from the list of animals exempt from meat harvesting regulations, ensures all edible portions of animals killed in B.C. are taken directly to the hunter’s residence, and requires the meat to be taken out first – before the hide or head. For non-resident trophy hunters coming to B.C. to hunt an animal solely for its hide, skull, or antlers this puts in place a prohibitive logistical challenge.

The bill also stops the government from letting non-resident hunters buy preferential access to limited-entry-hunt permits. And lastly, it bans people convicted of fisheries or wildlife offenses in B.C. and other jurisdictions from becoming fishing or hunting guides.

– 30 –

Media contact

Mat Wright, Press Secretary

+1 250-216-3382 | mat.wright@leg.bc.ca

Welcoming Elections BC investigation into political contributions

Weaver welcomes Elections BC investigation into political contributions

March 6th, 2017

For immediate release

VICTORIA B.C. – Today Andrew Weaver, Leader of the B.C. Green Party, welcomed the news that Elections BC is investigating potential contraventions of the Election Act.

“I’m thrilled that Elections BC will be investigating the information regarding indirect political contributions and other potential contraventions of the Election Act that were recently made public through the media,” says Weaver, also the MLA for Oak Bay-Gordon Head.

“However, this issue is so serious and of such consequence to British Columbians that I am also asking the RCMP to determine whether there are grounds for a criminal investigation. I will be sending the RCMP a letter this afternoon.”

Media reports over the weekend allege that many donations to the Liberals are made fraudulently or in violation of the Election Act and that the Liberals are encouraging this behaviour by holding cash for access events. The Liberals raised more than $12 million last year, more than any provincial political party in power. The B.C. NDP, which also accepts both corporate and union donations, have also allegedly pressured lobbyists for donations. The NDP have not released fundraising figures for 2016 but raised $3 million in 2015.

“It is crucial that all investigations be done in a thorough and timely manner, and that the results be released before the May 9th election. British Columbians have a right to know, before they cast their ballot, whether the B.C. Liberal Party or the B.C. NDP have broken the law.”

The B.C. Green Party stopped accepting corporate and union donations in September.

“This situation shows clearly the need for wholesale political finance reform in B.C,” says Weaver. “It’s time for British Columbians to take back B.C.”

– 30 –

Media contact

Mat Wright, Press Secretary

+1 250-216-3382 | mat.wright@leg.bc.ca

Responding to allegations of B.C. Liberal Party website hack

Responding to allegations of B.C. Liberal Party website hack

For immediate release

February 6th, 2017

VICTORIA B.C. – Andrew Weaver, leader of the B.C. Green Party issued the following statement regarding allegations that the B.C. Liberal Party website was hacked over the weekend:

“The B.C. Green Party condemns any attempt to hack or profit from the hack of a political opponent. Last week, the B.C. Liberals used leaked materials from the B.C. NDP to undermine their climate action platform announcement, and this week the B.C. Liberals’ website has apparently been hacked. This is gutter politics at its worst. It erodes trust in our democratic institutions and breeds mistrust in our systems of government. It is a net loss for the people of British Columbia. As B.C. Greens, my team and I are steadfast in our commitment to an honest, principled approach to politics that puts people at its centre, not dirty tricks and power.”

– 30 –

Media contact

Mat Wright, Press Secretary

+1 250-216-3382 | mat.wright@leg.bc.ca

Basic Income Part III: The Future of Work

1. Introduction

This post is the third in our series exploring the concept of a basic income and its implications in BC. Our backgrounder provided an overview of the concept, the issues we are facing today in BC, and the potential implications of a basic income policy. Our second post investigated in more detail the current state of poverty, welfare rates and social assistance in BC. We are grateful for the high level of engagement that our series continues to receive on social media and this website, including the large number of thoughtful comments. Below we continue to engage with the common themes in the responses we’ve received. This dialogue is very important in exploring ideas and creating good policies.

Many of you have noted the current scarcity of jobs and the precarious nature of much work today. A second theme has been disagreement about the role of basic income in either disincentivizing people to join the workforce, or providing people the freedom and self-sufficiency required to achieve personal and professional goals. Finally, many of you spoke with optimism about the potential of basic income to exert a beneficial and potentially transformational effect on society as a whole. In responding to your comments and sketching what we believe are some of the key issues, here we explore the social impacts of precarious employment, the trend towards increasing automation of jobs, and the role that basic income could play in the changing world of work.

2. Precarious Work

The world of work is changing, most dramatically due to technological advance, especially automation, but also due to a trend away from long-term, secure, full-time work with benefits, toward short-term, part-time, and contract-based work.

Finance Minister Bill Morneau stated recently that Canadians need to get used to “job churn”, defined as making a number of career changes in one’s life through short-term contract-based employment. Since the 2008-09 recession, the majority of jobs created have been part-time or temporary. The October 2016 Canadian Labour Force Survey highlights this trend: 44,000 net jobs were created across Canada in the month of October, but this number reflects a gain of 67,000 new part-time positions and a loss of 23,000 full-time positions. Men aged 25-54 have been hit particularly hard: full-time employment for this demographic declined by 63,000 positions over the past year, while part-time employment increased by 36,000 positions. The trend is the same in BC: 55,000 new jobs have been created since October 2015, but the majority (41,000) of these have been part-time positions.

Contract-based employment, which is often short-term, with fewer hours and without benefits, is also on the rise. Many speak of the rise of the “precariat” – a workforce that moves from job to job, taking temporary positions with no benefits and little job security. While some individuals prefer the flexibility of part-time or contract-based work, for most, it is not a choice: many are forced to take the jobs available, and suffer from insecurity and low incomes due to lower wages and fewer hours.

Some sectors are hit much harder than others by these trends: the natural resource industries, manufacturing, and education sectors, for example, have seen some of the largest increases in temporary and contract-based work in recent years. There are indications this trend will continue, with the majority of new jobs being part-time, temporary, or contract-based. This would mean significant implications for the financial security and well-being of huge numbers of people across British Columbia and beyond.

3. Automation

Recent years have also seen unprecedented technological advance in speed and scale, and there has been much talk recently about the impending robot revolution – when robots could increasingly replace humans in a variety of jobs, and the rate of automation outstrips the rate of job creation. We are already seeing the impact of technology on work: automated voice recognition software is already replacing many call centre workers, car assembly plants use more robots than people, and driverless cars and trucks are already significantly impacting the taxi and trucking industries.

Looking forward, a number of forecasts suggest the potential for the rapid elimination of jobs across a range of sectors: a study at the University of Oxford, for example, found that 47% of jobs in the U.S. are at “high risk” of computerization over the next two decades. The World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs report predicts that we are entering a fourth industrial revolution that will result in the net loss of 5 million jobs across 12 leading economies over just the next 5 years. Barack Obama’s 2016 economic report predicts that jobs paying less than $20/hour face an 83% likelihood of being automated, while jobs paying between $20 and $40/hour face a 33% chance.

Some argue that predictions about the effects of automation overstate the risk: that machine-caused unemployment has been predicted before and always been misguided; that automation lowers costs and creates new jobs; and that any transition would be gradual. Yet the rate of technological advance so far has exceeded most estimates. Furthermore, many of those speaking out most loudly about the disruptive potential of technology, and the need for a basic income policy to deal with the transition, come from within the tech industry itself, and thus have the most intimate knowledge of the technology and its future potential. Y Combinator, the Silicon Valley start-up incubator, is a major proponent of basic income as a way to smooth the disruption it expects to result from technological advance, and is currently running its own basic income pilot project in California.

We are already seeing the exacerbation of inequality as a result of technological advancement, as it further concentrates wealth in the hands of the few. Automation will further exacerbate inequality, as it disproportionately impacts low and moderate paying jobs and affects some sectors more than others: jobs in transportation, manufacturing, and office and administrative support are set to be hardest hit, and soonest. Bill Morneau recently specified that truck drivers and receptionists are most likely to see their jobs disappear in the coming years: these are the second most common occupations for men and women respectively across Canada, so it goes without saying that the social ramifications of large scale job loss in these occupations would be extremely significant.

4. The Role of Basic Income

If automation results in job loss at the rate many are predicting, the outcome could be an unprecedented level of structural unemployment. In this scenario, a basic income would make the transition more humane, as the alternative is a large percentage of people living on current social support systems like employment insurance and income assistance, which, as discussed in our last post, leaves many recipients below the poverty line. If inequality continues to rise, redistribution of the significant financial benefits of the robot revolution – especially for those adversely affected – is a moral imperative.

Basic income could also lessen the psychological strain on those affected by precarious work today, and on those whose work may be made redundant by machines in the future. Among the many comments we received, a number of you spoke to the emotional cost of dealing with uncertain work and an insecure future; in our last post we also touched on the psychological hardships of living on social assistance in BC. Some advocates of basic income even view it as a necessary means to prevent social breakdown resulting from the widespread unemployment and poverty that automation would cause. Basic income could also provide an essential way to keep the economy going by giving people the financial means to continue their participation in the market even if they are unable to find new jobs.

Basic income could also help mitigate against rising unemployment levels due to automation. To adapt to a changing world of work, people need the freedom and means to do so. Basic income could enable those affected by automation or the rise in precarious work to retrain for new professions, attend or return to university, college or trade school, or take entrepreneurial risks. Many basic income advocates view this flexibility as a promising way to spur further innovation and job creation, and create benefits for society as a whole. Basic income could also form part of a more visionary response to a changing world of work: by restoring a measure of financial security and freedom, it could help people create meaningful work (paid or unpaid) and foster social connections, as well as supporting volunteering work and community engagement.

5. Conclusion

At this juncture in our history, the dream of a stable, long-term career is disappearing for many, and the strong possibility exists that automation will fundamentally alter our economy and make many careers obsolete. We therefore have the obligation to create forward-thinking policies that enable us to cope with the magnitude of changes that may be coming our way. But we also have an opportunity to do more than just cope. We have the opportunity to harness these changes and create a more equitable and sustainable society that works better for all of us.

We want to know what you think about the future of work in British Columbia. Please share your thoughts on precarious work, the threat and opportunities of automation, what work means to you, and the role you think basic income could play in a shifting economy. Thank you in advance for your comments.

Basic Income Part II: The Current State of Poverty and Income Assistance in BC

This is the second post in our four-part series exploring the concept of “Basic Income”. Our first post focused on providing background information on the topic. It prompted more than 60 comments on this site and more than 450 comments on my MLA Facebook page. As a consequence, it is apparent to us that there is broad interest in the idea.

1. Responding to your comments

Our introduction to the concept of basic income received a huge number of thoughtful responses. Many shared their own stories about challenging periods in their lives: time spent living in poverty or on the edge of it, working in precarious or underpaid positions with uncertain futures, and struggling to raise a family or achieve personal goals in this context. We are grateful to everyone who took the time to share their feedback on the idea of a basic income, for the thoughtfulness of the comments and the support and commitment that so many showed to working towards a future that is more just and equitable for all, whether through a basic income policy or other means.

The comments showcased a number of common hopes that people hold for a basic income policy, dissatisfaction with the status quo, and concerns for the risks that a basic income could involve. In this post we will elaborate on some of the themes that we found in the responses, diving deeper into the situation we are in today.

In the responses to our backgrounder, the most widely expressed sentiment was hope in the idea that a basic income policy could end the poverty cycle, eliminate the traps that keep people in poverty throughout their lifetimes and across multiple generations, and treat those in need with greater dignity. In response, in this post we want to focus more closely on the current condition of poverty in BC and our response to it, and highlight how a basic income might offer an alternative solution.

2. Poverty and Social Assistance in BC

We have already highlighted BC’s higher than average rates of poverty, with between 11-16% of adults and 16-20% of children living in poverty, depending on the measure used. Poverty disproportionately affects children and single-parent families: more than half of all children living in single-parent families were living in poverty in 2013, compared to 13% for children in couple families. Aboriginal people, recent immigrants, and people with disabilities are also more vulnerable to poverty.

Estimates of poverty levels differ according to the measure used. The low income measure, low income cut-offs, and the market-based measure are three measures commonly used in Canada.

- The low income measure (LIM) is a relative measure, set at 50% of median adjusted household income.

- The low-income cut-off is an income threshold below which a family will likely devote a larger share of its income on the necessities of food, shelter and clothing than the average family. The average family spends 43% of their income on food, shelter, and clothing, whereas families below the low-income cut-off usually spend 63% of their income on these necessities.

- The market-basket measure is based on the estimated cost of purchasing a “basket” of goods and services deemed to represent the standard of consumption for a reference family of two adults and two children, including: a nutritious diet, clothing and footwear, shelter, transportation, and other necessary goods and services (such as personal care items or household supplies). The cost of the basket is compared to disposable income for each family to determine low income rates.

Each of these measures result in slightly different statistics, hence the range of numbers used.

3. Details of current social assistance programs

There are a myriad of programs that make up income assistance in BC, specific eligibility requirements, and a complex application process that may include interviews, home check-ins, and mandatory work search periods. In your comments, many of you spoke of the invasiveness, restrictiveness, and stigma of current income assistance programs.

Welfare rates in BC today are $610 per month for a single individual without a disability who is expected to look for work. The rates haven’t increased for nearly 10 years. Advocacy organizations estimate that a single individual on welfare has only $18 per week to spend on food; the organization Raise the Rates recently ran a challenge to illustrate the difficulty of eating on such a small budget. One individual who we spoke with recently shared his personal story of living on income assistance: he is disabled, and so receives income assistance for persons with disabilities, which totals just over $900/month. He wants to return to school to receive training and accreditation, but the strict limits on how much he can save have prevented him from doing so. He is seeking work, but to improve his prospects he needs to get more education, and the claw back of dollars earned has been a disincentive for him to seek out a low-paying job. Furthermore, the affordability crisis has affected him directly: he was evicted because the land on which he lived was being developed into condos, and his new rental unit requires almost all of his income, thus requiring him to rely on food banks for food. He calls being on income assistance “humiliating and constricting”. This individual’s story highlights a number of struggles that many face in trying to move their lives forward while on income assistance.

It’s important to note that many British Columbians living in poverty are not welfare recipients. Working poverty is a growing problem across BC: Vancouver had the second-highest rate of working poverty in the country (behind Toronto), at 8.7% in 2012, although this percentage is likely higher now given the recent affordability crisis affecting the region. The high cost of living, the low minimum wage, and the growth of precarious employment have contributed to rising levels of working poverty. The minimum wage was recently raised to $10.85/hour, whereas the estimated living wage is $20.02 in Victoria and $20.64 in metro Vancouver. The living wage is what a family needs to cover basic expenses, such as food, clothing, housing, child care, transportation, and a small savings in case of emergencies. It is calculated based on a two-parent two-child family, with both parents working full-time. The discrepancy between the minimum wage and the amount of income required to cover basic expenses leaves many families across our Province below the poverty line.

4. Basic income and poverty reduction

A basic income policy could offer a solution to poverty in BC, if the payments are constructed to ensure that all recipients, in different parts of the province, with different family sizes and different challenges, are able to live above the poverty line. If a basic income replaced our current income assistance programs, individuals in need would no longer have to prove themselves eligible or justify their need for assistance, through completing mandatory work searches, interviews, or home check-ins, for example. Simply falling below the income threshold would automatically qualify you. Replacing our invasive welfare system with a basic income that is framed as an automatic payment program, similar to the tax credits and payments many sections of our society receive today, could reduce significantly the stigma around receiving income assistance. This in itself could have a dramatic effect on the self-esteem and social inclusion of those in need of support.

One issue that is often brought up in discussions of basic income and poverty reduction is the issue of cost. The cost of a basic income policy is potentially significant but is hard to quantify, since it depends on a wide range of factors, including the amount paid, the eligibility requirements of recipients, and which services it will complement and which it will replace. These factors will be discussed in greater detail in a future post. However, it is essential that, in considering the question of cost, we consider the cost of maintaining the status quo, including the hidden and indirect costs to society of our current levels of poverty.

The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives estimates that poverty in BC costs society $8.1-$9.2 billion annually. This figure stems from the direct costs of social assistance programs to the government, as well as the adverse consequences of poverty, which have significant costs borne by society as a whole. The consequences of poverty include poor health, due to high levels of obesity, alcohol, tobacco and drug use, as well as inadequate nutrition and physical inactivity), high levels of stress and mental health problems, higher than average levels of domestic abuse, low literacy rates, poor educational performance, and high crime rates. The associated costs of these consequences show up through higher usage of public health care, increased policing needs and costs to the justice system, and lost productivity and economic activity.

As noted in our previous post, the basic income pilot project undertaken in Manitoba showed significant impacts on the healthcare system in particular: it reduced hospital visits by 8.5%. The decrease in hospital visits was attributed by researcher Evelyn Forget to the reduction of stress in low income families, which resulted in lower rates of alcohol and drug use, lower levels of domestic abuse, fewer car accidents, and lower levels of hospitalization for mental health issues.

Homelessness, which we explored in a series last winter, is inextricably linked to inadequate income for those working and receiving assistance, a lack of affordable housing, and inadequate access to support services. Homelessness has enormous costs to the BC Government, and a number of studies have found that it costs less to directly address the problem of homelessness and invest in prevention than it does to manage homelessness (see here and here, for example). A basic income could provide an integral part of ending homelessness, but it could not completely supplant other social services, such as supportive housing and mental health and addictions services.

The story of youth in transition is similar: as noted in the previous post, a recent report by the Vancouver Foundation finds that paying all youth ages 18-24 transitioning out of foster care a “basic support fund” of between $15,000-$20,000 would result in overall savings to the Provincial Government of $165-$201 million per year, due to the adverse outcomes youth in transition currently experience and their associated costs.

In your comments, many of you raised concerns specifically with the idea of paying youth a basic income without a work requirement, suggesting that doing so could undermine the development of a work ethic or discourage their entry into the work force. Given the range and magnitude of adverse outcomes that youth in transition currently experience, such a concern may not be warranted, or perhaps should not take priority over helping them avoid such outcomes by whichever means possible. Beyond youth specifically, there was a hesitation expressed by a number of commenters that a basic income would provide a strong disincentive for many people to work, and would thus undermine their sense of self-worth and identity. On the other hand, many of you expressed the mirror image of this thought: that a basic income would provide freedom from the constraints and stress that currently plague those on income assistance, allowing individuals to better their lives, go after their dreams and realize their potential. Which version of this thinking we adhere to depends to a great extent on our assumptions about what factors motivate and prevent people from working, and what gives people satisfaction and fulfillment. This issue will be further explored in our next post in this series.

5. Conclusion

We would appreciate further thoughts from you on the state of poverty and assistance in BC and whether you think a basic income could offer a solution. If you’d like to share a personal story or thoughts that you would prefer not to make public, please email us at andrew.weaver.mla@leg.bc.ca. In our next post, will explore the future of work, focusing on the rise of precarious employment and the effects of technological advance. We will discuss what these changes to the world of work will mean for all of us, and how a basic income policy might enable us to respond to these changes as a society.