Kinder Morgan

Kinder Morgan’s “enhanced” spill response regime: A closer look

This post is part of an ongoing series in which MLA Andrew Weaver will be sharing key information from inside the National Energy Board hearings on Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain pipeline proposal. To see previous posts, please click here.

What would happen if there were to be an oil spill on our coast?

How much of the oil could we actually expect to recover?

Kinder Morgan tried to address that second question in its application. Unfortunately, I found their conclusion to be rather unbelievable.

As a part of their application, Kinder Morgan submitted a report done by EBA, A Tetra Tech Company. The report was designed to evaluate Kinder Morgan’s enhanced oil spill response regime by simulating an oil spill.

The model they used to run this simulation is proprietary, so we have no way of assessing how valid or accurate it is. But we do know enough to raise some serious questions about the results.

The Oil Spill Simulation

When EBA ran its computer model, they started by outlining some basic assumptions. And that’s the key. In science, your projections are only as good as your initial assumptions. Unfortunately, the assumptions they chose are not representative.

Here’s what I mean:

When EBA ran its oil spill simulation, they had to pick a day of the year when the spill would occur. They also had to define what the weather was like that day, how quickly responders could get to the scene, when they would start their work, etc. All of these choices are called assumptions, which are converted to model input data. That is, using these assumptions, the model then has some hard data that it can use for its calculations.

Now, one thing we know in science is that the assumptions you choose can significantly influence the final result. For example, if you assume that responders can cleanup 100 tonnes of oil every hour then the final result will be much better than if you assume they can only cleanup 1 tonne every hour.

Questionable Assumptions

So what assumptions were used?

For starters, a pristine summer day in August was selected. They assumed that there would be 20 hours of sunlight to facilitate the spill response, that adverse weather conditions (such as waves and wind) would not prevent or complicate response in any way, and that there would be no toxic or explosive hazards preventing first responders from immediately approaching the spill. Finally, they assumed that it would take thirteen hours for all of the oil in the ship to be released into the surrounding environment.

Let’s unpack this.

First of all, we know from weather data provided by Trans Mountain (p. 366) that weather conditions along the route prevent spill response for 10% to 40% of the year. On top of that, we also know that even when spill response is occurring, the response becomes significantly less effective whenever waves are taller than 1m. Anyone who has been out on the water knows that we often have waves that are taller than 1m.

Secondly, to assume that it will take thirteen hours for all of the oil to spill out of two tanks seems like an arbitrary assumption. I asked Kinder Morgan to explain the reasoning behind it, but received no actual justification.

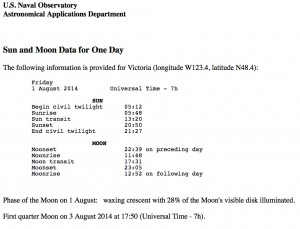

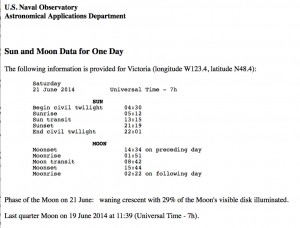

Finally, lets calculate how much sunlight there is in August. We know that the longest day in August will occur on August 1, as that is closest to the summer solstice (June 21). It’s relatively straightforward to plug the latitude and longitude of Victoria into the US Naval Observatory Astronomical Applications software to find that on August 1st, 2014 (for example) there was 15 hours and 2 minutes of daylight. Even if we stretch this to occur between the beginning and end of civil twilight, we only get 16 hours and 7 minutes (see figures below). This sure doesn’t seem like 20 hours to us. In fact even at the summer solstice, the longest day of the year, there is only 16 hours and 15 minutes of sunlight extending to 17 hours and 31 minutes if we include the beginning to end of civil twilight. In fact, if you wanted 20 hours of sunlight on any day in August you’d have to be at Tuktoyaktuk’s latitude (69.5° N). And that’s hardly relevant to conditions off southern Vancouver Island.

Figure: (a) Sunrise and sunset calculations for August 1, 2014 and (b) the summer solstice (June 21, 2014).

The Results

After selecting pristine conditions, the report concluded that 44.5% of oil could be recovered at sea outside of the immediate containment area and a further 18.6% could be recovered within the containment area thanks to Kinder Morgan’s enhanced spill response regime. That result may seem pretty good, although you might be wondering what happened to the other 36.9% of oil that was spilled.

But the unfortunate reality is that EBA’s result appears unbelievably high as far as oil spill recovery goes. According to the Federal Expert Tanker Safety Panel, on average only 5-15% of oil is actually ever recovered from a spill, even in optimal conditions.

So is Kinder Morgan’s plan just that good?

The short answer: Unlikely. Rather, by picking ideal assumptions, EBA came up with a result that isn’t necessarily representative of what would actually happen in a real spill.

Given this, I asked Kinder Morgan to redo their model analysis with more representative results. Unfortunately, they refused.

I can’t help but come back to the same basic point: British Columbians expect better.

And unless Kinder Morgan is going to step up and take oil spills seriously, they will never earn the social license they need to build their pipeline.

Confidence Lost in NEB Assessment Process for Trans Mountain Pipeline

At some point it’s time to say enough is enough.

For months now we’ve seen mounting evidence that the National Energy Board (NEB) hearings on the Trans Mountain pipeline are seriously flawed. Cross-examination has been declined, deadlines for submission of information are short, intervenors can’t get their questions answered, relevant concerns are being ignored, and attempts to fix the process are shut down by the very organization that is tasked with protecting our interests: the NEB.

Last week, Trans Mountain sued Burnaby residents for “trespassing” on public parkland and sought an injunction against obstruction to the work they were mandated to conduct. In essence, they were asking the courts to intervene in the democratic right of Burnaby residents to protest against a project that neither had their support, not that of the City of Burnaby.

At the same time, one of the most credible intervenors, Marc Eliesen, quit the hearing process. With over 40 years of experience in the energy sector, Eliesen is a former board member of Suncor Energy, CEO of B.C. Hydro, Chair of Manitoba Hydro and deputy minister in several federal and provincial governments. He issued a scathing letter to the National Energy Board outlining the reasons for his exit and specifically cited concerns that the NEB was failing to fulfill its role as an impartial, transparent review body.

Back in 2010 when the BC Provincial Government and the Federal Government signed the “Environmental Assessment Equivalency Agreement” the province chose to streamline the assessment process by unifying what had previously been two separate provincial and federal environmental reviews.

This could have worked well if the interests of British Columbians were properly taken into account during the Energy Board hearings. Unfortunately what we have seen is a federally-run process that is ignoring our concerns. It is imperative that we remedy this now, before it’s too late.

Enough is enough. Our provincial government must reclaim British Columbia’s right to have our own, made-in-BC, hearing process. They can and should do so by immediately issuing the 30 day notice, required to cancel its equivalency agreement for this project with the Federal government. British Columbia could then launch its own, separate, environmental assessment. It’s time for the government to step up and protect our interests for it’s clear that the National Energy Board is not doing so.

Made-in-BC Environmental Assessment Required for Pipeline Project

Media Statement: November 3, 2014

Made-in-BC Environmental Assessment Required for Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion Project

For immediate release

Victoria, B.C. – With evidence mounting that the National Energy Board hearings on the Trans Mountain pipeline has lost its legitimacy, Andrew Weaver, MLA for Oak Bay-Gordon Head and Deputy Leader of the BC Green Party, is calling on the BC government to immediately issue the 30 day notice, required to cancel its equivalency agreement with the Federal government, and launch its own, separate, environmental assessment process.

“In the past week alone we have seen Kinder Morgan sue Burnaby residents for trespassing on parkland and one of the most credible intervenors, Marc Eliesen, fully withdraw from the hearing process,” says Andrew Weaver. “These are the latest indications that British Columbians simply do not trust the federal review process.”

Mr. Eliesen, an expert with over 40 years experience in the energy sector, including as a former board member of Suncor Energy, former CEO of B.C. Hydro, former Chair of Manitoba Hydro and deputy minister in several federal and provincial governments, issued a scathing letter to the National Energy Board outlining the reasons for his exit. His letter cites concerns that the NEB is failing to fulfill its role as an impartial, transparent review body.

This comes following months of jurisdictional disputes in the City of Burnaby and ongoing frustration expressed by other intervenors over a flawed hearing process.

As the only B.C. MLA with intervenor status in the hearings, Andrew Weaver has been among those intervenors who have been advocating for a better process.

“We have been voicing our concerns about the review process for months and every time we do we get shut down by the National Energy Board. At some stage you have to recognize that the federal process is simply stacked against British Columbians and the only way to change that is for our provincial government to step up and reclaim its right to have its own, made-in-BC hearing process.”

The June 2010 equivalency agreement signed between the federal government and province set the review process for major pipeline and energy projects under the the National Energy Board, with final approval to be determined by the federal cabinet. The equivalency agreement for the Trans Mountain project can be cancelled with 30 days notice.

“The BC government needs to stand up for British Columbians,” says Weaver. “What we need is a made-in-BC environmental assessment that is controlled by British Columbians to ensure our concerns get respected and that our questions get answered.”

-30-

Media Contact

Mat Wright – Press Secretary, Andrew Weaver MLA

Mat.Wright@leg.bc.ca

Cell: 1 250 216 3382

Diluted Bitumen in BC Coast Waters

This post is part of an ongoing series in which MLA Andrew Weaver will be sharing key information from inside the National Energy Board hearings on Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain pipeline proposal. To see previous posts, please click here.

Diluted Bitumen in BC Coast Waters

The ongoing dispute between the City of Burnaby and Trans Mountain has been in the news a fair amount lately. It’s evident to me that the residents of Burnaby are being well-represented by their elected leaders and civic employees. As part of the Trans Mountain National Energy Board hearings, the City of Burnaby has been asking pointed and difficult questions, raising critical issues of concern, and communicating effectively with their residents. The City of Burnaby is rightly concerned about the potential risk of a diluted bitumen spill at the proposed expanded terminal facility in Burrard Inlet, as well as the potential ramification of having an enhanced pipeline capacity through it’s neighbourhoods or underneath Burnaby Mountain. But what hasn’t received enough attention is the potential risks that our coastal communities face once diluted bitumen is loaded onto tankers.

Bitumen is the raw product extracted from the Alberta oil sands. It is heavier and more viscous than conventional crude oil and so must be either upgraded or diluted with other petroleum products in order for it to flow through pipelines. This combination of bitumen and diluent is referred to as diluted bitumen, or dilbit. There is very little research on how dilbit and the chemicals used to dilute it behave if a spill occurs in fresh water or marine environments.

A recent federal government study concludes that, unlike other crude oils, dilbit will sink in the presence of suspended particulate matter (e.g. sediment particles in the ocean). Suspended particulate matter is very common in B.C.’s coastal waters, meaning that any dilbit spill will likely lead to submerged oil. Currently we have no ability to clean up oil that sinks below the surface, making dilbit a particularly risky substance to transport.

So for coastal British Columbia, a specific reason for concern regarding the transport of dilbit is that we know very little about how it would behave if it were to be spilled into a marine environment. Evidence from the July 2010 Kalamazoo River dilbit spill in Michigan also provides a pretty clear indication that dilbit would sink when combined with sediments. One thing we have no shortage of in our coastal waters is suspended sediments. Next time you travel on a BC ferry from Swartz Bay to Tsawwassen, have a look at the water. Water originating from the Fraser River has a very distinct milky colour associated with its high sediment content.

Please provide your references

As you might imagine, the scientific uncertainty as to the fate and behaviour of a potential dilbit spill prompted me to pose a number of questions to Trans Mountain through the National Energy Board hearing process. Some of my questions were relatively straightforward:

On page 11, of the report A Comparison of the Properties of Diluted Bitumen Crudes with Other Oils, submitted to the National Energy Board as part of the Trans Mountain application, the study of Tsaprailis et al 2013 is referred to. It is the only study cited with respect to penetration of various types of oil into sand. As I could not find the reference, I simply asked the obvious questions?:

- Is this study peer reviewed?

- Is this study published in a scientific journal?

- Are there any peer reviewed scientific journal studies that have examined dilbit penetration into sands? If so, please list them.

Here’s the answer I got:

- Trans Mountain is unaware of the review process used for the Tsaprailis et al 2013 report but assumes that it was peer reviewed by the client (AIEES).

- Trans Mountain does not have this information.

- Trans Mountain is unaware of any scientific publication on dilbit penetration into sediment other than Brown et al. (1992).

You can imagine my frustration. I am trying to examine the scientific evidence underpinning Trans Mountain’s submission and I can’t get access to, or information about, key references they are using in their application.

It gets worse.

On page 5 of the report A Study of Fate and Behaviour of Diluted Bitumen Oils on Marine Waters, that Trans Mountain submitted in support of their application, it states: “the literature review resulted in only six reported studies focused specifically on dilbits in available on-line searches.” All I asked for was information on how I could find them:

- Please list these six studies with URLs so that I can access them.

- Do any of these studies appear in the peer-reviewed scientific literature?

You would think it would be trivial to respond to these. But instead of an answer, I was directed to a bibliography that included 75 references which may or may not include the six that were being referred to. Fortunately the National Energy Board compelled Trans Mountain to provide a full and adequate response to my original question and I await receipt of the six references.

Does Diluted Bitumen Sink or Float on Marine Waters?

Transmountain relied heavily on work they commissioned in the report entitled: A Study of Fate and Behaviour of Diluted Bitumen Oils on Marine Waters. This is referred to as the so-called Gainford study. This study undertook tank experiments using saline water (typical of Burrard inlet) that did not include suspended sediments. Yet according to the aforementioned federal study:

“high-energy wave action mixed the sediments with diluted bitumen, causing the mixture to sink or be dispersed as floating tarballs”

and

“Under conditions simulating breaking waves, where chemical dispersants have proven effective with conventional crude oils, a commercial chemical dispersant (Corexit 9500) had quite limited effectiveness in dispersing dilbit.“

So I asked the obvious questions, noting that the tank experiments were all conducted with conditions claimed to be typical of Burrard Inlet. Have any tank experiments been conducted:

- with more saline conditions typical of the Strait of Juan de Fuca? If not, why not?

- with colder conditions typical of winter? If not, why not?

- in the presence of strong horizontal and/or vertical sheer? If not, why not?

- in the presence of whirlpools? If not, why not?

- in the presence of downwelling conditions with downwelling velocities reaching greater than 40-50 cm/s as observed in [observed tidal fronts in the region]? If not, why not?

I received, what can only be described as a very odd response: “Additional studies were conducted by the Government of Canada (2013), under more saline conditions and different temperatures.” In other words, I was referred right back to the report that I cite above claiming that dilbit has the potential to sink. In response to this reply I responded:

“This response is unacceptable. I am aware of the government on Canada studies. As noted in [the Government of Canada (2013) ] report does not provide any details of any research that may or may not get done. I submit that Trans Mountain has not adequately answered the question(s), and request that an appropriate answer be provided.”

To which all I received from Trans Mountain was:

“The requested information has been provided and Trans Mountain‘s response is full and adequate. The response provides the Board with all necessary information pertaining to this matter. There is no further response required and supplementing the original response will not serve any purpose. Trans Mountain notes that if the Intervenor disagrees with the information contained in the response, it may contest the information through evidence or final argument.“

This interaction is very troubling to me since in its report entitled Review of Trans Mountain Expansion Project: Future Oil Spill Response Approach Plan, Recommendations on Bases and Equipment, Full Report, submitted by Trans Mountain as evidence in support of its application, it states that:

“During the course of the ten days test the diluted bitumen floated on the water and could be retrieved effectively using conventional skimming equipment.“

It is clear to me that unless compelled to do so, Trans Mountain does not plan to conduct additional tank studies. The question I ask is this. Is it the responsibility of the taxpayer to fund federal government science in direct support of industry? Or should the industrial proponent of a project be required to pay for the necessary scientific studies? The answer is obvious to me.

Summary

In summary, it is clear that there is a profound gap in scientific knowledge as to what would happen if diluted bitumen were to be released into the Salish Sea.

Yet we must not forget that in British Columbia dilbit is already being piped through the existing Kinder Morgan line to Burnaby where it is loaded onto tankers. About one tanker a week laden with dilbit is passing along the coast of the Oak Bay-Gordon Head riding on its way to refineries in Asia or California.

Was there an environmental review process when dilbit replaced traditional crude in the existing line? If not, why not?

The British Columbia government has outlined five conditions that must be met for their acceptance of heavy oil pipelines projects. These are

- Successful completion of the environmental review process. In the case of Enbridge, that would mean a recommendation by the National Energy Board Joint Review Panel that the project proceed;

- World-leading marine oil spill response, prevention and recovery systems for B.C.’s coastline and ocean to manage and mitigate the risks and costs of heavy oil pipelines and shipments;

- World-leading practices for land oil spill prevention, response and recovery systems to manage and mitigate the risks and costs of heavy oil pipelines;

- Legal requirements regarding Aboriginal and treaty rights are addressed, and First Nations are provided with the opportunities, information and resources necessary to participate in and benefit from a heavy-oil project; and

- British Columbia receives a fair share of the fiscal and economic benefits of a proposed heavy oil project that reflects the level, degree and nature of the risk borne by the province, the environment and taxpayers.

I support these five conditions. But in addition and for the reasons outline above, the BC Green Party and I have added a sixth condition:

- A moratorium for dilbit transport along the British Columbia Coast.

The justification is clear. The BC government’s five conditions must be applied to existing as well as future projects.

Unpacking Trans Mountain’s “Credible Worst-Case” Oil Spill

This post is part of an ongoing series in which MLA Andrew Weaver will be sharing key information from inside the National Energy Board hearings on Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain pipeline proposal. To see previous posts, please click here.

Trans Mountain’s “Credible Worst-Case” Oil Spill

As part of their analysis, Trans Mountain conducted oil spill scenarios for what they consider to be “credible worst-case” and smaller-sized spills.

The purpose of running these scenarios is to estimate the likely impact a spill would have on our communities and our environment, as well as to gauge their ability to respond to a spill. The problem is, Trans Mountain’s “credible worst case” spill scenario only accounts for a small fraction of the oil that could actually spill.

Here’s what I mean:

A single oil tanker will carry over 110,000 tonnes of oil. Yet, according to Trans Mountain, the maximum size of a “credible worst case” spill (i.e. the largest spill they think could ever actually happen) would only be 16,500 tonnes. That’s only 15% of the oil carried by a single ship.

So where does their definition of a “credible worst case” spill come from?

Trans Mountain undertook a probability analysis, factoring tanker size, shipping lanes and traffic, as well as other data. They found that 90% of their spill scenarios were smaller than 16,500 tonnes in size. Trans Mountain then simply “defined” this to be their “credible worst-case” scenario. That is, they defined ‘credible worst-case’ as the 90th percentile.

That means there is not a single report or study in the entire 15,000 page application that considers what would happen if more than 15% of the oil on a tanker were to spill.

I found this profoundly troubling. In my first round of questions, I asked Trans Mountain to provide an analysis of the risks and impacts of having 100% of the oil spill. This is called a total loss scenario. While it fortunately isn’t a common scenario, it certainly does fall into the realm of possibility.

Unfortunately, Trans Mountain responded by saying that a total loss scenario was not “viable” or “credible”, that my request was therefore not relevant, and so refused to provide the sought after analysis. They base this on the fact that “there has not been any total loss of containment scenarios involving a double hull tanker, ever, to date…”

The Problem with Trans Mountain’s “Credible Worst-Case”

I have two big concerns with Trans Mountain’s logic.

First, the very fact that Trans Mountain’s “credible worst case” oil spill only accounts for 90% of spills means that there is a 10% chance that an oil spill will be larger than their “credible worst case”. 10% isn’t some distant possibility—it’s a very plausible scenario. In fact, the Exxon Valdez spilled roughly 35,000 tonnes of oil—more than double the size of Trans Mountain’s defined “credible worst-case” scenario. The Atlantic Empress released 287,000 tonnes of crude in 1979 after it caught fire and sank in the Caribbean. In 1983 Castillo de Bellver exploded off the coast of South Africa and released 50,000 to 60,000 tonnes of light crude into the sea. In 2002, Prestige split in half and sank off the coast of Spain releasing 63,000 tons. And of course, there are other examples. By refusing to even consider the possibility of these larger spills, they are ignoring spill scenarios that are certainly possible and that would have a devastating impact on our coast.

Second, while it may be true that so far no double-hull tanker has spilled 100% of its oil, this is far from a solid argument. The fact is, policies requiring all new tankers to be constructed with double-hulls are relatively new. It is only within the last 20 years that this has become a mandatory requirement. So, while a total loss incident involving a double-hull tanker has not occurred to date, these ships have not been in use long enough for such a justification to be made with much certainty.

This leads me to two basic questions:

How can Trans Mountain credibly say that they have provided a full analysis of the risks and impacts of marine oil spills, when they refuse to even consider the possibility of more than 15% of oil spilling?

How can British Columbians trust that Trans Mountain can actually clean up a spill, if the largest spill they are prepared for only accounts for a small fraction of the oil onboard?

If you ask me, they can’t.