Pipelines

Final Round of Questions Submitted to Trans Mountain

Media Statement: January 15, 2015

Andrew Weaver Submits Final Round of Questions on Trans Mountain Pipeline

For Immediate Release

Victoria B.C. – Today, Andrew Weaver, MLA for Oak Bay-Gordon Head and Deputy Leader of the B.C. Green Party, submitted nearly 100 additional question to Trans Mountain as a part of the second and final round of intervenor Information Requests in the National Energy Board hearings on Kinder Morgan’s proposed Trans Mountain oil pipeline.

The second round of Information Requests marks the final opportunity intervenors will have to test the evidence submitted by Trans Mountain in its proposal. Dr. Weaver’s questions focus on human health risks associated with the project and follow-up on his previous questions relating to the risks, impacts and response capacity associated with a potential oil spill.

“I continue to engage in this process because I believe it’s important to give a voice to my constituents and to British Columbians who worry that their concerns are being ignored,” says Andrew Weaver. “However, I remain deeply concerned that the process itself is fundamentally flawed.”

In the first round of Information Requests, Dr. Weaver submitted nearly 500 questions, while the roughly 400 intervenors collectively submitted over 10,000 questions. Over 2000 of the responses they received from Trans Mountain were officially challenged by intervenors as being inadequate. The National Energy Board (NEB) only ruled in intervenors’ favour in fewer than 5% of the instances, raising significant concerns about the integrity of the process.

“Many of the answers I received in the first round simply didn’t answer the questions I asked,” says Andrew Weaver. “The lack of substantive response from Trans Mountain and the lack of support from the NEB showed a disregard for the essential role that intervenors play in the hearings.”

Intervenors have been increasingly critical of the hearing process, noting that the absence of oral cross-examination has seriously undermined their ability to receive answers to even the most basic questions about the pipeline proposal.

In light of escalating issues with the process, Andrew Weaver continues to call on the B.C. Government to pull out of the Environmental Assessment Equivalency Agreement that it signed with the Federal Government and hold its own, independent hearing process.

“Until the B.C. government reclaims the province’s right to have its own made-in-BC hearing process, actively participating in the NEB hearings is the only way we have to properly represent British Columbians’ concerns and examine the Trans Mountain Pipeline proposal.”

Click here to see the questions submitted to the National Energy Board.

Media Contact

Mat Wright – Press Secretary, Andrew Weaver MLA

mat.wright@leg.bc.ca

1 250 216 3382

Constituency Report – Review of the Fall Session and Issues in the Community

The Fall 2014 session of the Legislature has concluded with the passage of the LNG emission and taxation bills. Watch Andrew Weaver report on the debates and votes, along with events and issues that affect the riding of Oak Bay – Gordon Head and everyone around the province.

Thank you to SHAW TV for providing this community service.

Cleaning up a heavy oil spill on the BC Coast: The Trans Mountain capacity

This post is part of an ongoing series in which MLA Andrew Weaver will be sharing key information from inside the National Energy Board hearings on Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain pipeline proposal. To see previous posts, please click here.

If Kinder Morgan builds its pipeline, the number of oil tankers passing by our cities and along our coast will increase by almost 600%.

With every tanker comes the risk of an oil spill. I therefore want to take some time to discuss how we would clean up a spill. In particular, since Trans Mountain is required by the National Energy Board to show how it would respond to a spill, I think it is important to see what they are proposing.

The Current Oil Spill Response Capacity

To understand Kinder Morgan’s proposal, we first need to understand the current standards. Unfortunately, a study commissioned by the B.C. government last year showed just how woefully inadequate our current standards are.

Oil spill response in B.C. is managed by the Western Canada Marine Response Corporation (WCMRC). WCMRC is required to be able to respond to a spill that is as large as 10,000 tonnes of oil. This may seem like a lot, but to put it in context the Exxon Valdez oil spill was 40,000 tonnes and a single tanker will be carrying over 100,000 tonnes of oil.

Not only that, but the fact that WCMRC is able to respond to a 10,000 tonne spill does not actually mean it is able to recover the full 10,000 tonnes. In fact, according to the Federal Tanker Safety Expert Panel, “Evidence suggests that mechanical recovery rates, in optimal conditions, are usually only between 5% and 15% of the oil spilled.” This is because despite existing equipment, it’s often hard to contain and recover spilled oil.

So where does this leave Kinder Morgan?

Kinder Morgan’s Enhanced Spill Response Capacity

As a part of their application, Kinder Morgan is proposing to improve on current standards. In their “Future Oil Spill Response Approach Plan” Kinder Morgan proposes increasing WCMRC’s capacity so that it can respond to a 20,000 tonne spill. It also proposes reducing response times so that WCMRC would get to a spill site quicker and start cleaning it up before more of the oil has had a chance to spread. Implementing this enhanced response plan would likely be costly—it would require additional personnel, equipment, staging locations, etc.

It’s certainly a step in the right direction. But here’s the catch.

First of all, Kinder Morgan does not have direct control over whether this plan is implemented or not. They have worked with WCMRC to develop the proposal, but ultimately, it will be up to WCMRC and federal legislation to determine what the standards are. If standards are not legislated federally, then the WCMRC will have a harder time justifying the costs to the companies that fund it (including Kinder Morgan). You therefore cannot evaluate the risks and impacts associated with the pipeline on the assumption that this proposal will be implemented. There is simply no guarantee.

Not only that, but this plan still falls far short of what is needed to cover the risks of the project. A single tanker will carry over 100,000 tonnes of oil. Kinder Morgan itself has acknowledged that according to its own calculations there is a 10% probability that a spill will be larger than 16,500 tonnes. Cleanup capacity for anything beyond 20,000 tonnes will be significantly delayed while resources are brought in from other areas. Any delay, as Kinder Morgan has noted, will decrease the effectiveness of recovery efforts as oil spreads beyond containment areas.

Finally, I have already talked about the Federal Government studies that show that diluted bitumen—the heavy oil that would be transported by tanker—sinks in the presence of suspended particles. Unfortunately, Kinder Morgan has not proposed any capacity to clean-up sunken oil. I believe that this is simply unacceptable.

I’m glad that Kinder Morgan is making an effort to propose an enhanced oil spill response capacity. Given that they have been loading oil tankers on our coast for year now, this effort is long overdue. Unfortunately, it also comes up short of anything that can truly be called “effective”.

Just how effective can a spill response be off our coast?

This post is part of an ongoing series in which MLA Andrew Weaver will be sharing key information from inside the National Energy Board hearings on Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain pipeline proposal. To see previous posts, please click here.

How do you actually clean up an oil spill?

And why is it that, on average, only 5-15% of oil is ever recovered from a spill?

There are a lot of factors that impact the effectiveness of clean-up efforts: Response time, size of the spill, weather conditions, number of personnel available to respond, availability of equipment, etc.

One of the biggest factors is simply the equipment itself. Oftentimes, the equipment only works under certain conditions, so I decided to explore this a bit further. I wanted to determine under what conditions the equipment works—and how often it doesn’t.

Here’s what I found:

Skimmers and boom lines are two of the most important pieces of equipment used to clean up an oil spill. Whereas boom lines are used to contain oil in an enclosed space, skimmers are used to recover spilled oil from the surface of the ocean.

As you can imagine, both booms and skimmers work best when the ocean is calm. As wave height increases, the oil spreads beyond the boom lines and mixes below the surface, making it hard to recover with skimmers.

In fact, the Western Canada Marine Response Corporation (WCMRC)—the organization responsible for responding to oil spills in B.C.—lays out all of this information for us.

It turns out that booms and skimmers work best when waves are less than 1m tall. As soon as waves are taller than 1m, booms and skimmers are “difficult to execute and become less effective” (p. 29). Once the wave height reaches 1.5 m, skimming and booming operations would be stopped entirely because they are so ineffective.

We sometimes have a pretty stormy coast, so I asked Kinder Morgan to identify the amount of time each year that wave height is:

- Less than 1m (skimmers and booms are effective)

- Between 1m and 1.5m (skimmers and booms are less effective)

- More than 1.5m (skimmers and booms are stopped entirely)

Unfortunately, in their response Kinder Morgan grouped all wave heights that are less than 1.5 m into one category, so we don’t know how often their response would be “less effective”. That said, we do know what percentage of the year spill response simply will not work due to wave heights higher than 1.5m.

It turns out that, on average, between 10% and 20% of the year WCMRC would not be able to use skimmers or booms because the waves are too high. In fact, WCMRC wouldn’t even be required to respond to an oil spill for that much of the year.

If, however, we take the data from Race Rocks—an island just outside of Victoria—it quickly rises to 40% of the year. That’s essentially three days a week, every week, when spill response would be stopped because the waves are too high.

Let me reiterate—those numbers do not include the time when spill response is less effective but still possible. Kinder Morgan still hasn’t clearly provided us with those numbers.

Now, I sincerely hope we never have a spill on our coast. But I believe strongly that we need to be prepared— just in case. What these numbers suggest is that for 10%-40% of the year we are not prepared at all.

And that’s a problem.

Kinder Morgan’s “enhanced” spill response regime: A closer look

This post is part of an ongoing series in which MLA Andrew Weaver will be sharing key information from inside the National Energy Board hearings on Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain pipeline proposal. To see previous posts, please click here.

What would happen if there were to be an oil spill on our coast?

How much of the oil could we actually expect to recover?

Kinder Morgan tried to address that second question in its application. Unfortunately, I found their conclusion to be rather unbelievable.

As a part of their application, Kinder Morgan submitted a report done by EBA, A Tetra Tech Company. The report was designed to evaluate Kinder Morgan’s enhanced oil spill response regime by simulating an oil spill.

The model they used to run this simulation is proprietary, so we have no way of assessing how valid or accurate it is. But we do know enough to raise some serious questions about the results.

The Oil Spill Simulation

When EBA ran its computer model, they started by outlining some basic assumptions. And that’s the key. In science, your projections are only as good as your initial assumptions. Unfortunately, the assumptions they chose are not representative.

Here’s what I mean:

When EBA ran its oil spill simulation, they had to pick a day of the year when the spill would occur. They also had to define what the weather was like that day, how quickly responders could get to the scene, when they would start their work, etc. All of these choices are called assumptions, which are converted to model input data. That is, using these assumptions, the model then has some hard data that it can use for its calculations.

Now, one thing we know in science is that the assumptions you choose can significantly influence the final result. For example, if you assume that responders can cleanup 100 tonnes of oil every hour then the final result will be much better than if you assume they can only cleanup 1 tonne every hour.

Questionable Assumptions

So what assumptions were used?

For starters, a pristine summer day in August was selected. They assumed that there would be 20 hours of sunlight to facilitate the spill response, that adverse weather conditions (such as waves and wind) would not prevent or complicate response in any way, and that there would be no toxic or explosive hazards preventing first responders from immediately approaching the spill. Finally, they assumed that it would take thirteen hours for all of the oil in the ship to be released into the surrounding environment.

Let’s unpack this.

First of all, we know from weather data provided by Trans Mountain (p. 366) that weather conditions along the route prevent spill response for 10% to 40% of the year. On top of that, we also know that even when spill response is occurring, the response becomes significantly less effective whenever waves are taller than 1m. Anyone who has been out on the water knows that we often have waves that are taller than 1m.

Secondly, to assume that it will take thirteen hours for all of the oil to spill out of two tanks seems like an arbitrary assumption. I asked Kinder Morgan to explain the reasoning behind it, but received no actual justification.

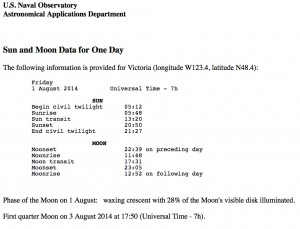

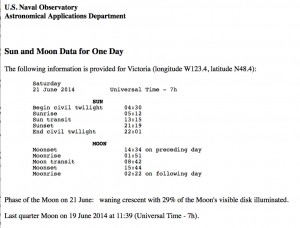

Finally, lets calculate how much sunlight there is in August. We know that the longest day in August will occur on August 1, as that is closest to the summer solstice (June 21). It’s relatively straightforward to plug the latitude and longitude of Victoria into the US Naval Observatory Astronomical Applications software to find that on August 1st, 2014 (for example) there was 15 hours and 2 minutes of daylight. Even if we stretch this to occur between the beginning and end of civil twilight, we only get 16 hours and 7 minutes (see figures below). This sure doesn’t seem like 20 hours to us. In fact even at the summer solstice, the longest day of the year, there is only 16 hours and 15 minutes of sunlight extending to 17 hours and 31 minutes if we include the beginning to end of civil twilight. In fact, if you wanted 20 hours of sunlight on any day in August you’d have to be at Tuktoyaktuk’s latitude (69.5° N). And that’s hardly relevant to conditions off southern Vancouver Island.

Figure: (a) Sunrise and sunset calculations for August 1, 2014 and (b) the summer solstice (June 21, 2014).

The Results

After selecting pristine conditions, the report concluded that 44.5% of oil could be recovered at sea outside of the immediate containment area and a further 18.6% could be recovered within the containment area thanks to Kinder Morgan’s enhanced spill response regime. That result may seem pretty good, although you might be wondering what happened to the other 36.9% of oil that was spilled.

But the unfortunate reality is that EBA’s result appears unbelievably high as far as oil spill recovery goes. According to the Federal Expert Tanker Safety Panel, on average only 5-15% of oil is actually ever recovered from a spill, even in optimal conditions.

So is Kinder Morgan’s plan just that good?

The short answer: Unlikely. Rather, by picking ideal assumptions, EBA came up with a result that isn’t necessarily representative of what would actually happen in a real spill.

Given this, I asked Kinder Morgan to redo their model analysis with more representative results. Unfortunately, they refused.

I can’t help but come back to the same basic point: British Columbians expect better.

And unless Kinder Morgan is going to step up and take oil spills seriously, they will never earn the social license they need to build their pipeline.