In recent years, governments and industry have become more and more interested in supporting so-called nature based climate solutions. So what are such solutions? The Nature Conservancy provides a concise definition: Nature-based climate solutions “are actions to protect, better manage and restore nature to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and store carbon.”

Such solutions aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions (mitigation) fall into two categories: 1) those that the enhance the uptake and storage of carbon within natural ecosystem; 2) those that reduce the emissions of greenhouse gases (e.g., carbon dioxide and methane) from natural ecosystems.

While the above definition recognizes the link between natural ecosystems and the global carbon cycle, nature based solutions also play a critical role in climate change adaptation strategies. A more complete definition that includes both their roles has been offered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and subsequently used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

“Nature-based Solutions are actions to protect, sustainably manage, and restore natural and modified ecosystems that address societal challenges effectively and adaptively, simultaneously benefiting people and nature.“

Below I attempt to highlight the important role that such solutions play in both climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies. But I try to put such solutions in the bigger context of what needs to be done to meet the challenge of global warming. I’ll attempt to outline why governments and industry appear to be so supportive of such solutions, yet point out the danger of over-relying on them.

To be clear, nature-based climate solutions have a crucial role to play. Cumulative anthropogenic fossil carbon emissions from 1750 to 2021 have been 474 GtC (billions of tons of carbon), while deforestation and land use changes have contributed another 203 GtC. That is, anthropogenic disruption of natural ecosystems has accounted for about 30% of historical greenhouse gas emissions, so it seems reasonable to expect nature-based climate solutions to have an important role to play moving forward. But there are limits. In fact, a recent paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggested that nature-based solutions could be used to meet 20% of the required emission reductions to be implemented prior to 2050 to keep global warming to below 2°C. I’ve pointed out for years (and summarized these views again recently), that the 1.5°C target was not attainable even when proposed in the 2015 Paris Accord, due to socioeconomic inertia in our built environment, the role of atmospheric aerosols, and potential effects from the permafrost carbon feedback.

Examples of Nature Based Climate Solutions

To start, I thought it would be illustrative to provide a few examples of nature based climate solutions in action. This list is by no means comprehensive, but rather serves solely to give the reader a sense of what such solutions entail.

The most obvious example of a nature based solution is planting trees. Widespread deforestation, particularly in the creation of pastures for cattle grazing and land for farming or other human uses, has provided the lion’s share of the historical 203 GtC released to the atmosphere. Reforestation (planting trees where they once were) and afforestation (planting trees in places where they weren’t historically present) both have the potential to draw carbon from they atmosphere as they grow. But of course, if we want to use tree planting in carbon budget accounting, we would also have keep track of the carbon released during forest fires.

The most obvious example of a nature based solution is planting trees. Widespread deforestation, particularly in the creation of pastures for cattle grazing and land for farming or other human uses, has provided the lion’s share of the historical 203 GtC released to the atmosphere. Reforestation (planting trees where they once were) and afforestation (planting trees in places where they weren’t historically present) both have the potential to draw carbon from they atmosphere as they grow. But of course, if we want to use tree planting in carbon budget accounting, we would also have keep track of the carbon released during forest fires.

Urban planners also incorporate tree management in their climate adaptation strategies. For example, they recognize that increasing the tree canopy can help keep cities cooler in the summer than they would otherwise be. Homeowners, for example, might plant deciduous trees in their front yard that blocks the sun from their main windows in the summer, but allow the sunshine in during the late fall and winter once the leaves have fallen.

The use of biochar to enhance the properties of soil has also been proposed as a potential nature-based climate solution. Biochar (a charcoal like substance) is created through a process known as biomass pyrolysis. (high temperature decomposition of plant material). The addition of biochar to agricultural soil leads to enhanced soil carbon uptake and storage, reduced requirement for fertilizer use (and hence reduced nitrous oxide emissions), and improved water use efficiency. Other agricultural nature-based solutions involving tiling practices, crop/grazing rotations, cover crops etc. have also been proposed.

The use of biochar to enhance the properties of soil has also been proposed as a potential nature-based climate solution. Biochar (a charcoal like substance) is created through a process known as biomass pyrolysis. (high temperature decomposition of plant material). The addition of biochar to agricultural soil leads to enhanced soil carbon uptake and storage, reduced requirement for fertilizer use (and hence reduced nitrous oxide emissions), and improved water use efficiency. Other agricultural nature-based solutions involving tiling practices, crop/grazing rotations, cover crops etc. have also been proposed.

In the coastal ocean, mangroves, salt marshes and seagrass meadows more efficiently capture and store carbon than land based, slow-growing forests. Many of these so called “blue carbon” sinks have been stressed by human activity in research decades and steps have been taken to both preserve and enhance their health and extent. These rich, biodiverse ecosystems also play key roles in climate change adaptation as they serve to protect coastal erosion from storms and sea level rise.

In the coastal ocean, mangroves, salt marshes and seagrass meadows more efficiently capture and store carbon than land based, slow-growing forests. Many of these so called “blue carbon” sinks have been stressed by human activity in research decades and steps have been taken to both preserve and enhance their health and extent. These rich, biodiverse ecosystems also play key roles in climate change adaptation as they serve to protect coastal erosion from storms and sea level rise.

Recognizing the importance of nature-based solutions, the Canadian federal government developed a natural climate solutions fund to protect, enhance and preserves Canada’s biodiverse and carbon rich wetlands, grasslands and forests, in addition to a commitment to plant two billion trees over a ten-year period.

What’s required to stabilize atmospheric temperature

As most everyone is aware, the goal of the internationally-negotiated Paris Agreement is to limit global warming to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels while pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C. Yet we’ve known for more than 15 years that such a target would ultimately require rapid decarbonization and the introduction and scale-up of negative emission technology. In a paper entitled Long term climate implications of 2050 reduction targets that we published in 2007, we note in the abstract (and discussed below):

“Our results suggest that if a 2.0°C warming is to be avoided, direct CO2 capture from the air, together with subsequent sequestration, would eventually have to be introduced in addition to sustained 90% global carbon emissions reductions by 2050.“

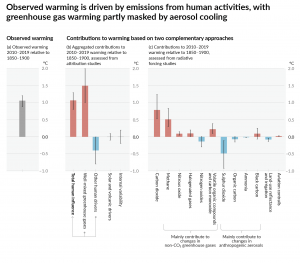

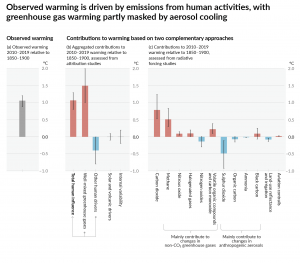

Earth has already warmed by ~1.1-1.2 °C since preindustrial times and if worldwide fossil fuel combustion was immediately eliminated, the direct and indirect net cooling effect of atmospheric aerosol loading would rapidly dissipate through gravitational settling and precipitation scavenging of these aerosols. As such, the source of the ~0.5 °C aerosol cooling realized since the preindustrial era would be eliminated (see Figure 1), thereby taking the Earth rapidly to ~1.6-1.7 °C warming. The Earth would warm further as we equilibrate to the present 523 ppm CO2e (NOAA 2023) greenhouse gas loading in the atmosphere (only 417 ppm of which is associated with CO2), and that is not including the committed warming from the permafrost carbon feedback that would add another 0.1 to 0.2 °C this century (Macdougall et al, 2013).

Figure 1: Observed global warming (2010-2019 relative to 1850-1900) and the contribution to this net warming by observed changes to natural and anthropogenic radiative forcing. Reproduced from IPCC (2021).

Let’s once more explore the level of decarbonization required to keep warming below 2°C (recognizing that 1.5°C is no longer attainable). I present results from the UVic Earth System Climate model discussed in Weaver et al. (2007) and my book Keeping our Cool: Canada in a Warming World.

Starting from a pre-industrial equilibrium climate, I force the UVic model with observed natural and human-caused radiative forcing until the end of 2005. After 2005, future trajectories in emissions must be specified. Each of the post-2005 scenarios I use assumes that contributions to radiative forcing from sulphate aerosols and greenhouse gases other than carbon dioxide remained fixed throughout the simulations. An alternative way of looking at this is that any increase in human- produced, non-carbon dioxide greenhouse gases is assumed to be balanced by an increase in sulphate aerosols (or some other negative radiative forcing). This assumption should be viewed as extremely conservative, since most future emissions scenarios have decreasing sulphate emissions and increasing emissions of non-carbon dioxide greenhouse gases.

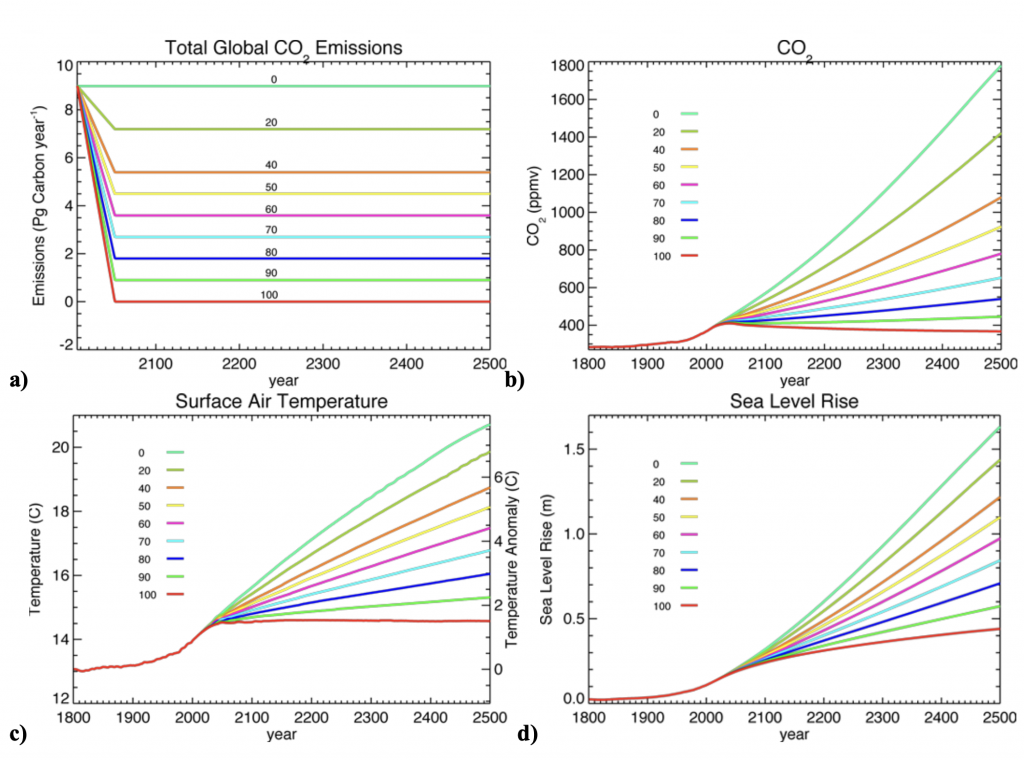

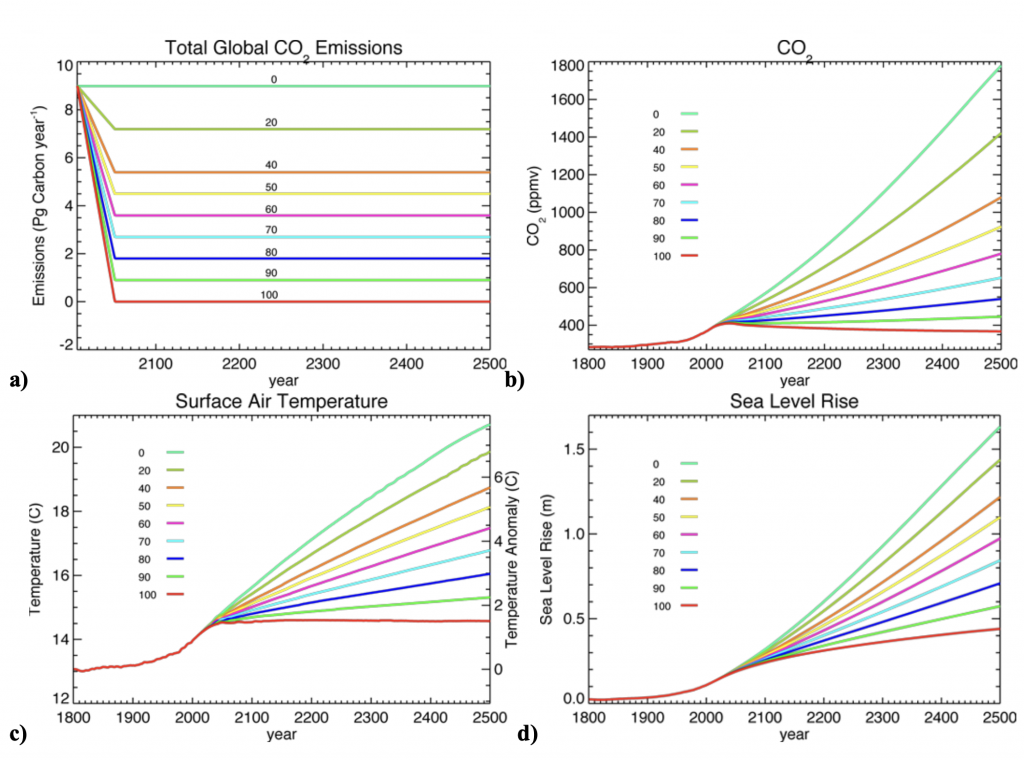

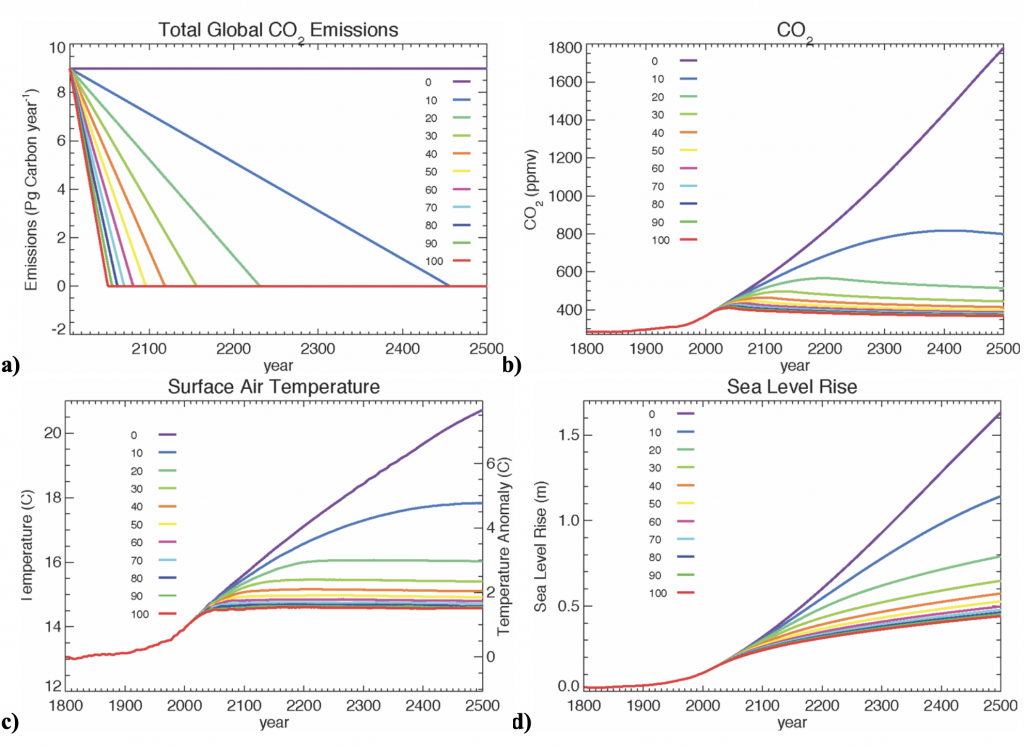

We’ll start by examining the effects of a hypothetical international policy option that linearly cuts emissions by some percentage of 2006 levels by 2050, and maintains emissions constant thereafter until the year 2500 (see Figure 2a). Of course, my baseline case of constant 2006 emissions is substantially more optimistic than the IPCC scenarios, some of which have 2050 emissions at more than double 2006 levels. The various pathways in emissions lead to atmospheric carbon dioxide levels in 2050 ranging from 407 ppm to 466 ppm, corresponding to warming relative to 1800 of between 1.5°C and 1.8°C (Figure 2b and Figure 2c). As the twenty-first century progresses, the atmospheric carbon dioxide levels and warming begin to diverge between scenarios, and by 2100 the range is 394 ppm to 570 ppm (we are presently at 417 ppm), with a warming of between 1.5°C and 2.6°C. None of the emissions trajectories lead to an equilibrium climate and carbon cycle in 2500, although the 90% and 100% sustained 2050 emissions reductions have atmospheric carbon dioxide levels that are levelling off. Of particular note is that by 2500, the scenario depicting a 100% reduction in emissions leads to an atmospheric carbon dioxide level below that in 2006, although global mean surface air temperature is still 0.5°C warmer than in 2006 (1.5°C warmer than 1800). While this version of the UVic Earth System Model only calculates the thermal expansion component of seal level rise and ignores contributions from glacier and ice sheet melt, the results shown in Figure 2d indicate that sea level rise still has not equilibrated even after 500 years.  Figure 2: (a) Observed anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions from 1800 to 2006 (red) followed by linear reductions of 0–100% of 2006 levels by 2050. From 2050 onwards emissions are held constant. Transient evolution of globally-averaged (b) atmospheric carbon dioxide, (c) surface air temperature, and (d) sea level rise due to thermal expansion for all experiments. Note that the sea-level curves have no contribution from the melting of land-based ice.

Figure 2: (a) Observed anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions from 1800 to 2006 (red) followed by linear reductions of 0–100% of 2006 levels by 2050. From 2050 onwards emissions are held constant. Transient evolution of globally-averaged (b) atmospheric carbon dioxide, (c) surface air temperature, and (d) sea level rise due to thermal expansion for all experiments. Note that the sea-level curves have no contribution from the melting of land-based ice.

All simulations that have less than a 60% reduction in global emissions by 2050 eventually break the threshold of 2°C warming this century. Even if emissions are eventually stabilized at 90% less than 2006 levels globally (1.1 billions of tonnes of carbon emitted per year), the 2°C threshold warming limit is eventually broken well before the year 2500. This implies that if a 2°C warming is to be avoided, direct CO2 capture from the air, together with subsequent sequestration, would eventually have to be introduced in addition to 90% reductions in global carbon emissions.

I purposely kept emissions constant after 2050 in my idealized scenarios to illustrate that cutting emissions by some prescribed amount by 2050 is in and of itself not sufficient to deal with the problem of global warming. Even if we maintain global carbon dioxide emissions at 90% below current levels, we eventually break the 2°C threshold. This is because the natural carbon dioxide removal processes can’t work fast enough to take up the emissions we emit to the atmosphere year after year. Any solution to global warming will ultimately require the world to move towards net zero emissions carbon which requires the introduction and global scale up of negative emission technology.

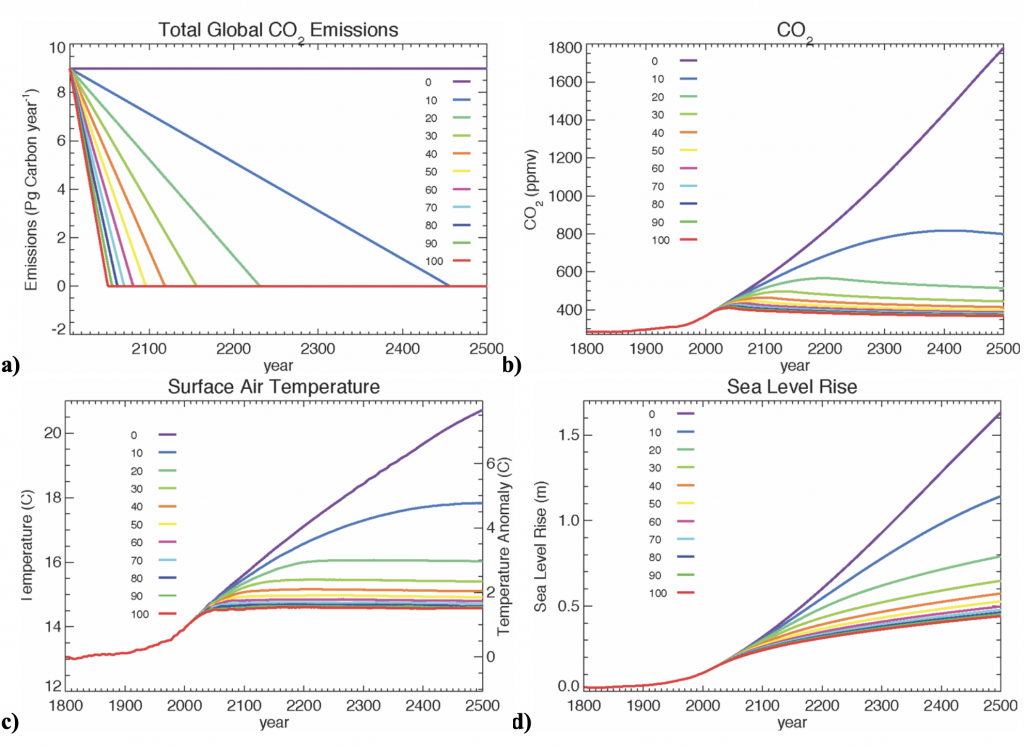

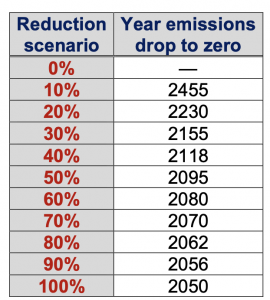

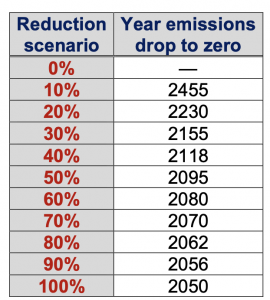

Figure 3: As in Figure 2 but the emissions in (a) continue the linear decrease until zero emissions are reached. The year in which zero emissions is reached is indicated in the table below.

Now let’s examine the effects of another hypothetical international policy option that starts from the results obtained in the previous suite of experiments at 2050 but now continues to linearly decrease emissions at the same rate until zero emissions are reached. The resulting emissions are shown in Figure 3a and the date at which emissions fall to zero is given in table to the right.

Now let’s examine the effects of another hypothetical international policy option that starts from the results obtained in the previous suite of experiments at 2050 but now continues to linearly decrease emissions at the same rate until zero emissions are reached. The resulting emissions are shown in Figure 3a and the date at which emissions fall to zero is given in table to the right.

If we keep emissions on a linearly decreasing emissions path to carbon neutrality, it turns out that in the UVic model about 45% or larger reductions (relative to 2005 levels) are required by 2050 if we do not wish to break the 2°C threshold. And peak atmospheric carbon dioxide levels reach a little over 450 ppm before settling down to slightly above 400 ppm. Notice that in all cases, even though emissions have gone to zero, sea level continues to rise. It’s further important to note that these simulations were conducted and published in 2007 and assumed the hypothetical scenario of an immediate curtailing of emissions. The reality is global fossil carbon emissions (excluding land use emissions) were 10.1 GtC (billions of tonnes of carbon) in 2021 which is a 25% increase from 2005 levels (when they were 8.1GtC).

In this section I have tried to emphasize that the only means of stabilizing the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is for humanity to achieve net zero carbon emissions. While the implementation of nature-based solutions provides some additional time before net zero must be reached to avoid breaking the 2°C guardrail, there is a danger that such efforts are being overly promoted by governments and industry to allow them to maintain the status quo of oil, gas and coal exploration and combustion.

It’s a question of timescale

Millions of years ago when the atmosphere had much higher concentrations of carbon dioxide, trees, ferns, and other plants were abundant. These plants used the sun’s energy, together with carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and water, to create glucose or sugar and release oxygen back to the atmosphere (photosynthesis). As the years went by, plants would grow and die, and some of these dead trees and other vegetation would fall into swampy waters depleted in oxygen. In this environment, the organic matter only partially decayed and so turned into peat, a precursor for coal formation. Over time, shallow seas covered some of the swampy regions, depositing layers of mud or silt. As the pressure started to increase, the peat was transformed, over millions of years, into brown coal, then soft coal, and finally hard coal.

Millions of years ago when the atmosphere had much higher concentrations of carbon dioxide, trees, ferns, and other plants were abundant. These plants used the sun’s energy, together with carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and water, to create glucose or sugar and release oxygen back to the atmosphere (photosynthesis). As the years went by, plants would grow and die, and some of these dead trees and other vegetation would fall into swampy waters depleted in oxygen. In this environment, the organic matter only partially decayed and so turned into peat, a precursor for coal formation. Over time, shallow seas covered some of the swampy regions, depositing layers of mud or silt. As the pressure started to increase, the peat was transformed, over millions of years, into brown coal, then soft coal, and finally hard coal.

A similar process occurred within shallow seas where ocean plants (e.g., phytoplankton) and marine creatures would die and sink to the bottom to be buried in the sediments below. Over millions of years, the sediments hardened to produce sedimentary rocks, and the resulting high pressures and temperatures caused the organic matter to transform slowly into oil or natural gas. The great oil and natural gas reserves of today formed in these ancient sedimentary basins.

Today when we burn a fossil fuel, we are harvesting the sun’s energy stored from millions of years ago. In the process, we are also releasing the carbon dioxide that had been drawn out of that ancient atmosphere (which had much higher levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere than today). So, unless we can actually figure out a way to speed up the millions of years required to sequester carbon from the atmosphere and to convert dead plants back into peat and then coal (or oil and gas) the idea that we can somehow stop global warming solely through nature-based solutions isn’t realistic.

Nevertheless, and I reiterate, there are many positive reasons for planting new forests (afforestation), replanting old forests (reforestation), or reducing the destruction of existing forests (deforestation), including the restoration of natural habitat and the prevention of loss of biodiversity. However, trees only store carbon over the course of their lifetime. When these trees die, or if they burn, the carbon is released back to the atmosphere.

The danger of over reliance on nature based solutions

While nature-based solutions have an important role to play in climate change adaptation and the preservation of biodiversity, there is a growing danger that governments, industry and the general public will come to rely on them as a means to maintain the status quo.

Let’s take British Columbia’s LNG experience as an example.

In the lead up the the 2013 provincial election I repeatedly pointed out the economic and environmental folly of somehow believing that BC would build prosperity through liquifying natural gas and shipping it to Asia. In fact, I quantified my concerns in one of the first blog posts I wrote in the BC Legislature. British Columbia residents were being told that at least five major LNG facilities would be built in BC by 2020. Today we have none, so I would suggest that my concerns about the economics of LNG were spot on.

In the lead up the the 2013 provincial election I repeatedly pointed out the economic and environmental folly of somehow believing that BC would build prosperity through liquifying natural gas and shipping it to Asia. In fact, I quantified my concerns in one of the first blog posts I wrote in the BC Legislature. British Columbia residents were being told that at least five major LNG facilities would be built in BC by 2020. Today we have none, so I would suggest that my concerns about the economics of LNG were spot on.

In 2018, when it was clear that BC’s plans for LNG were not going to materialize, the BC NDP picked up where the BC Liberals left off and further sweetened the tax credit regime for LNG Canada, the one remaining major LNG company left in BC. It was clear to me that British Columbia could not meet its legislated greenhouse gas reduction targets if the LNG Canada project was ever built and I wrote a detailed blog post pointing out that it was time for both the BC NDP and the BC Liberals to level with British Columbians about LNG. The BC NDP government remained adamant that BC could still reduce emissions to 40% below 2007 levels by 2030. I remained skeptical and feared that this target can only be achieved through creative carbon accounting and appealing to “nature-based solutions”. I believe I was and remain correct. The analysis above and my earlier blog posts should make that obvious. And nobody should be surprised to see Shell Canada now promoting its efforts to ensure “the protection and restoration of natural ecosystems such as forests, grasslands and wetlands” as a central component to its greenhouse gas mitigation strategy. Of course, there is no mention of greenhouse gas emissions from the ever increasing area burnt by Canadian wildfires, nor the emissions being triggered as permafrost thaws and the previously frozen organic matter begins to decompose.

The Darkwoods Forest Carbon project offers a glimpse into what is likely being considered by BC government and industry decision-makers as a means of offsetting emissions from the natural gas sector. The problem with this is threefold.

First, claiming that the preservation of a forest should be considered a carbon offset using an argument that the wood would otherwise be harvested is a bit like me say to you: “give me $10,000 or I will buy a gas-guzzling SUV”! Second, if you want to claim a carbon credit for planting a tree, then you have to also accept a debit if that tree, or another, burns down. Third, there is no international mechanism to get credit for such a nature-based offset and these are purely considered voluntary.

Summary

In this post I have tried to outline the important role that nature-based climate solutions play amid the suite of policy options available to government and industry. The cautionary tale is that while these represent important contributions to a jurisdiction’s overall climate change adaptation and mitigation strategy, they cannot take away from the requirement to decarbonize energy systems immediately. As outlined in a recent article published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B by researchers from Oxford University in the UK, “there are concerns over their reliability and cost-effectiveness compared to engineered alternatives, and their resilience to climate change.”

For years I have noted that the signing of the Paris Agreement in 2015 had immediate consequences for oil, gas and coal exploration. At the time of its signing, and given the availability of existing technologies, the Paris Agreement translated to the notion that effective immediately, no new oil, gas or coal infrastructure could be built anywhere in the world if we want to keep warming to below 2°C. This follows since such major capital investments have a long payback time; you don’t build a natural gas electricity plant today only to tear it down tomorrow. Socioeconomic inertia in the built environment also suggests that the capital stock turnover time would be decades, not years.

Nature based-solutions are really a natural branch of other so-called Carbon Dioxide Removal geoengineering projects. Another solution that has received some attention of late concerns increasing the alkalinity of surface waters through dissolution of limestone. This geo-engineering fix was one of many examined by the IPCC in a 2005 special report assessing the possibility of capturing and storing carbon dioxide. To sequester 1 kilogram of carbon dioxide without the negative effects associated with acidification 3.5 kilograms of calcium carbonate (limestone) would have to be artificially dissolved in the ocean. Today, about 6.6 Gt of limestone is mined annually. If the entirety of this global production was dissolved in the ocean, about 1.9 Gt of carbon dioxide could be sequestered annually (or 0.5 Gt of carbon equivalent). This represents about 5% of the world’s 2021 global carbon dioxide emissions. A twenty-fold increase in limestone mining to sequester our present-day emissions would have enormous energy implications (with their concomitant emissions), not to mention the potential environmental impacts of such expanded mining activities. We would also have to stop producing cement, which uses this limestone, throughout the world, meaning that concrete could no longer be used in construction. It should be clear that attempting to modify surface alkalinity using the world’s limestone resources is not a serious proposition to combat global warming.

Nature based-solutions are really a natural branch of other so-called Carbon Dioxide Removal geoengineering projects. Another solution that has received some attention of late concerns increasing the alkalinity of surface waters through dissolution of limestone. This geo-engineering fix was one of many examined by the IPCC in a 2005 special report assessing the possibility of capturing and storing carbon dioxide. To sequester 1 kilogram of carbon dioxide without the negative effects associated with acidification 3.5 kilograms of calcium carbonate (limestone) would have to be artificially dissolved in the ocean. Today, about 6.6 Gt of limestone is mined annually. If the entirety of this global production was dissolved in the ocean, about 1.9 Gt of carbon dioxide could be sequestered annually (or 0.5 Gt of carbon equivalent). This represents about 5% of the world’s 2021 global carbon dioxide emissions. A twenty-fold increase in limestone mining to sequester our present-day emissions would have enormous energy implications (with their concomitant emissions), not to mention the potential environmental impacts of such expanded mining activities. We would also have to stop producing cement, which uses this limestone, throughout the world, meaning that concrete could no longer be used in construction. It should be clear that attempting to modify surface alkalinity using the world’s limestone resources is not a serious proposition to combat global warming.

So in summary, despite the many benefits of nature-based solutions, what is required to keep global warming to below 2°C (or, frankly, to stabilize it at any level), is the immediate transition towards the decardonization of global energy systems along with the widespread introduction of negative emission technology, such as direct air carbon capture and deep underground storage. At this stage, I am of the belief that this remains the only hope humanity has for a long term solution to this problem. We can take comfort in the very real successes of nature-based solutions, and their many co-benefits, but we cannot take our eyes off the scale of the challenge before us. Fortunately, all the solutions are known. It is a matter of individual, institutional, corporate and political will as to whether or not we will achieve the goals of net zero emissions in the future.