Transportation

Vancouver’s TransLink (not Transit) Referendum

Over the next few months the residents of Metro Vancouver will help shape the future of public transit in their region. The question is clear and the stakes are high:

“Do you support a new 0.5% Metro Vancouver Congestion Improvement Tax, to be dedicated to the Mayors’ Transportation and Transit Plan? Yes or No.“

The vote has sparked a heated debate about TransLink, public transit, how to fund it, and its future in the Lower Mainland. No matter what the result of this plebiscite is, it will have repercussions that echo across British Columbia.

A Flawed Plebiscite

The residents of Metro Vancouver are being asked to accept or reject a 0.5% regional increase to the provincial sales tax. All of the money raised by this tax will be used to fund much needed improvements to Metro Vancouver public transit system. I have already written about this referendum and the abdication of responsibility it represents. Governance is about dealing with issues; not letting them fester and hoping someone else takes the blame. True leadership means listening to stakeholders and being open to compromises. It means making difficult, necessary and, at times, unpopular decisions.

The provincial government was given an opportunity to display this kind of leadership. Metro Vancouver expects one million new residents in the next 30 years, putting an extra strain on an already overburdened transportation system. It is a problem that requires decisive, well thought out action that engages stakeholders and fixes systemic problems. Instead the government decided to duck its responsibility and hold a plebiscite.

The referendum began as a campaign promise. During the 2013 election the BC Liberals were down in the polls and grasping at straws. In a move that put politics before leadership, the Premier promised that any new TransLink tax would go before a referendum. Public Transit is a complicated issue; it’s a balancing act of providing services and staying affordable. It requires listening to the citizens of today while working for those of tomorrow.

Unfortunately, the BC Liberals ignored this.

With a focus on purely political outcomes, they waded, half-cocked, into a complex issue and we are witnessing the results. They set in motion a $6 million dollar referendum, the first in Canadian history asking voters to directly approve a tax, while ignoring the serious structural issues in Vancouver’s public transit.

Perhaps this explains why the province is asking the wrong question. They could have followed the Premier’s original plan and asked a more nuanced question. In her own words, “It needs to be a multiple-choice question. A simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’ doesn’t do justice to the questions that are there.” This would have given voters more options, saving them from choosing between another regressive tax hike and a struggling transit system. Better yet, they could have explored a key concern by asking voters about the organization that runs public transit in Metro Vancouver. They could have asked a question about TransLink.

The latest polls paint a very clear picture. Only 12% of respondents, on either side, have a positive opinion of TransLink. Contrast this with the 39% that believe “TransLink is very broken and needs a complete overhaul”’ and the additional 25% who have a generally negative view of the organization. In fact, 61% of those planning to vote No, believe that TransLink cannot be trusted with the extra funds to be raised by this tax. The Vancouver referendum is turning into a vote about TransLink and the management of its 1.5 billion dollar annual budget instead of a vote about transit.

Despite all of this, Transportation Minister Todd Stone has made it clear that he will not reform TransLink, regardless of the plebiscite’s results. The government promised a referendum while refusing to listen to residents of the Lower Mainland. They’re not just voting No to the tax increase, they’re voting No to TransLink. People are calling for change. People are calling for reform. And the government is pretending that they can’t hear them.

There are serious problems with TransLink. And here I am not only talking about the examples of waste outlined by the No Transit Tax campaign. Improving inefficiency and eliminating wasteful processes is important, but will not come close to raising the needed funds.

My concerns have more to do with the structure of TransLink and the unfortunate relationship it has had with the province. In my view this referendum has given us the opportunity to open a conversation about TransLink. It has to regain the trust of the people it serves. Regardless of how Metro Vancouver votes, there needs to be change. In order to understand how to move forward, I think it is important to first look back, not only at the referendum but also at TransLink itself.

A History of Interference

TransLink was set up by the BC NDP and took over services from BC Transit in 1999. It was envisioned as a more accountable, more local and a more fiscally independent organization. It was given an expanded mandate including roads and bridges, in addition to buses and trains. Unlike its predecessor, the board of TransLink was elected. Along with this accountability came the new power to raise taxes independently, allowing for more financial security and long term planning. Over the next decade this oversight, and the original vision, for TransLink, would be stripped away, leaving us with the transportation authority we have today.

The Provincial Government’s meddling began months before TransLink officially began operations. Glen Clark’s NDP government announced the construction of the Millennium Line, a system that would use SkyTrain technology and run only through NDP ridings. This biased route earned it the nickname a ‘train to nowhere’. Besides the obvious partisan criticism, it also drew the ire of the local officials. The new line would derail their plans for a light rapid transit to Coquitlam and saddled TransLink with significant costs.

Not to be outdone, Gordon Campbell’s Liberal government also blocked a transit line to Coquitlam, this time to build the Canada Line. This SkyTrain project connected the Vancouver International Airport with the downtown core. The project was a centerpiece for their Olympic proposal and faced heavy resistance within the TransLink board. They had serious concerns over cost and believed that the resources were much better spent elsewhere. They voted against the government’s proposal twice before finally backing down, accepting the project with substantial fiscal safeguards.

The delay prompted Transportation Minister Kevin Falcon to announce sweeping changes to the TransLink board. He claimed the elected board was too narrow in their thinking, especially in the debates surrounding the Canada Line. In other words, he was saying that the local board created to serve local citizens was too local in its thinking.

TransLink was designed as a regional authority, which was transparent and fully accountable to the people Metro Vancouver. As a body with the authority to raise taxes and seriously impact the lives of residents throughout the region it needed to have a social license to operate. It had to be attentive to the needs of the people. This all ended with Minister Falcon’s interventions.

Governance and Reform

Before the Minister’s sweeping changes were made, a board of fifteen directors ran TransLink. Twelve of the directors were mayors and councillors appointed by Metro Vancouver. The remaining three were Provincial MLAs, although these seats usually remained vacant. The directors made tough decisions but had to engage with voters to build support for policies.

The authority is now run by two boards. One is still elected — the Mayors’ Council consisting of all elected representatives in the Metro Vancouver area. The council has the power to oversee the sale of major assets as well as approve various proposals by the TransLink Board of Directors.

Mayors’ Council also choose the members of the Board of Directors. Perhaps ‘sort of choose’ is a better way to say this. Every year the Mayors’ Council receives a short list of individuals nominated by a screening panel made up of government and professional representations. The Mayors than choose new directors from this list. If they do not choose enough directors to fill the empty seats the decision reverts to the screening panel.

This appointed board has a wide range of responsibilities including developing long term plans, approving TransLink’s operating budget and running the ‘day-to-day’ operations of TransLink. Despite this significant power there is no way to hold board members accountable. They can only be fired by provincial legislation, and don’t have to worry about re-election. The process was intentionally designed to be a step removed from democracy, mirroring port and airport legislation. The key difference between TransLink and any port authority is that TransLink has the ability to raise taxes on more than 2 million people.

Two board seats have been recently added for mayors and two more, still vacant, have been added for province. While these tentative steps towards engagement and democratization are a step in the right direction they do not go nearly far enough.

Regardless of the results of the plebiscite, TransLink’s governance must be reformed. It is far too big and far too powerful to be so far removed from democracy. There has been much talk about the need for change, but not nearly enough on how this change could occur. An interesting place to start this discussion would be to examine the way public transit is governed in London, England.

Like Metro Vancouver, London’s transportation system is run by a large organization (Transportation for London — TFL) with a broad mandate including buses, trains, roads and cyclists. Unlike Metro Vancouver the ultimate power is in the hands of the mayor. This democratically elected representative sets an overall vision for the city and designs the policies and the strategies that will bring it into practice.

The mayor is also the chair of the TFL Board of Directors. This board is responsible for implementing the vision and strategies put forward by the mayor. Each of these directors is handpicked by the mayor and is drawn from a broad spectrum and currently includes the Executive Chairman of British Airways and a licensed taxi driver.

Transposing this model onto TransLink, the authority would still be run by two boards but the power dynamic would shift. The elected and accountable Mayors’ Council would be responsible for deciding organizational goals and the policies which could bring them to fruition. The mayors currently sitting on the board of directors could move to chair positions. The Council as a whole could appoint the other directors directly and be able to end their tenure early, should the need arise.

This is by no means the only avenue for change, it is just one model that has worked in one place. The new TransLink must be the result of significant consultation and debate and I only mean to illustrate one potential alternative.

Conclusion

This referendum shouldn’t have happened. At best, it is a misguided dereliction of duty on the part of the provincial government. At worst it is a cynical political ploy. If Premier Clark was serious about bringing democracy back to TransLink then she should have done so. The Premier should have reformed the organization, bringing back democracy consistently, instead of throwing voters a bone when it’s politically convenient.

It is unfortunate that the province decided to take us down this path. It has not stopped people from expressing their distrust of TransLink, but it has left them without a proper forum to call for change. Regardless of how the Lower Mainland votes there needs to be a serious conversation about TransLink. And this conversation should not only be about its flaws. It should also be about how we can fix them. The call for change may have begun with a referendum but it doesn’t need to end there.

Finally, as I wrote in the article in February, if I lived in Vancouver, I would vote ‘Yes’. I would do so reluctantly. I would do so begrudgingly. And I would do so frustratedly, knowing that my provincial government had abdicated its leadership responsibility.

These are my thoughts on TransLink. What are yours?

Trying to Protect the BC coast from expansion of thermal coal & diluted bitumen exports

During the committee stage of Bill 12, The Federal Port Development Act on Thursday afternoon, I put forth a number of amendments in an attempt to protect the British Columbia coast from the expansion of thermal coal and heavy oil (diluted bitumen) exports. These were the amendments mentioned in my earlier post on Bill 12. All amendments were defeated. Below I provide a brief excerpt from Hansard.

First Amendment

A. Weaver: With respect to the minister, the reason I have troubles with this legislation is…. We are not debating the Canada Marine Act. I will come to that.

Under the Canada Marine Act, the federal government can sell federal land in a port to a port authority, which could be administered by the province of British Columbia. In selling the land to the port authority, the Species at Risk Act and the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act no longer have any jurisdiction because the land is no longer owned by the federal government. It is now within the port authority, administered by the province of British Columbia.

My concern, therefore, with respect to an undertaking is that heavy oil or thermal coal experts would then no longer have to worry about Species at Risk or Canadian Environmental Assessment Act implications in any development there. The problem with that is that we don’t have anything in the province of British Columbia as a Species at Risk Act.

In essence, what’s happening in accepting an agreement like this, through an undertaking involving either coal or heavy oil, as we will discuss in section 3, is we are essentially saying that we in British Columbia can exempt such development from the federal Species at Risk Act and we have nothing to fall upon here in British Columbia. We can fall on the Environmental Assessment Act.

Frankly, with respect to what we’ve seen with Kinder Morgan and Enbridge, the province has done an admirable job in terms of representing the interests of British Columbia. I have not seen that with respect to thermal coal, and for this reason I do have two amendments I would like to bring here to specifically exclude from ‘undertaking’.

[To amend as follows:

By adding the text shown as underlined:

Section 1

“undertaking” means an undertaking, or an undertaking in a class, designated for the purposes of section 64.1(2)(a) of the Canada Marine Act; excluding an undertaking, or an undertaking in a class, relating to the import or export of thermal coal.]

That is the first amendment I so move.

The Chair: The amendment was proposed by the member for Oak Bay–Gordon Head. It reads: “‘undertaking’ means an undertaking, or an undertaking in a class, designated for the purposes of section 64.1 (2)(a) of the Canada Marine Act, excluding an undertaking, or an undertaking in a class, relating to the import or export of thermal coal.”

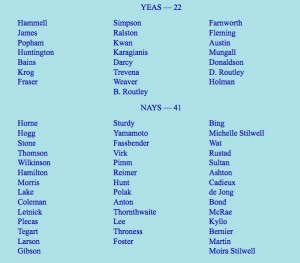

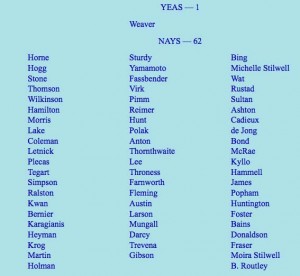

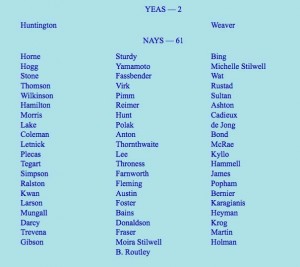

Amendment negatived on the following division:

The Chair: Hon. Members, stay in your seats. The member is going to move another amendment.

Second Amendment

A. Weaver: As I mentioned earlier, I have a legal backgrounder from West Coast Environmental Law, which talks about the passage of Canada Marine Act, which we’re talking with respect to the “undertaking” definition here.

That would significantly increase the powers of port authorities, allow the federal government to off-load its responsibility over shipping in federal ports, etc. The changes now allow port authorities to buy federal land and infrastructure from the government and then lease those lands to companies or authorize companies to use them for as long as the port authority has control over them.

Once sold, those lands would no longer be federal property, meaning they would not be subject to terrestrial species protection under the Species at Risk Act.

Seeing as we have no species at risk act here in British Columbia, this raises some concern, which is why I move, again, an amendment to amend as follows:

[By adding the text shown as underlined:

Section 1

“undertaking” means an undertaking, or an undertaking in a class, designated for the purposes of section 64.1 (2)(a) of the Canada Marine Act excluding an undertaking or an undertaking in a class relating to the import or export of heavy oil.]

In light of the fact that we do not import heavy oil that probably is moot, but certainly export is a big issue that’s facing us now.

The Chair: Hon. Members, if the House waives the time we will proceed right away. Do we have consent?

Leave granted.

Amendment negatived on the following division:

Third Amendment

A. Weaver: Thank you to the minister for the answer. My concern here is that the province would enter an agreement and potentially get into a position where the Species at Risk Act is not applicable or in force. I have an amendment here I’d like to move, which is to amend section 2 as follows:

[By adding the text shown as underlined:

Section 2

With the prior approval of the Lieutenant Governor in Council, a member of the Executive Council may enter into an agreement on behalf of the government.

If

(a) the province has first enacted provincial legislation comparable in power and scope to the Species at Risk Act (S.C. 2002, c. 29), and

(b) any and all port developments subject to the agreement that would have previously triggered a review under the Species at Risk Act (S.C. 2002, c. 29) prior to the royal assent of Bill C-43 (2014), automatically trigger a review under the legislation referenced in subsection (a).]

On the amendment.

A. Weaver: This is a piece of legislation trying to ensure that British Columbia enforces species-at-risk legislation. If it doesn’t enforce the federal one — which it can’t, of course — it has to produce its own if it’s going to enter an agreement as per the discussion here.

The Chair: Hon. Members, it’s an amendment moved by the member for Oak Bay–Gordon Head regarding the Species at Risk Act.

Amendment negatived on the following division:

Serious Concerns with the Federal Port Development Act

Serious Concerns with the Federal Port Development Act: Huntington, Weaver

March 3, 2015

For Immediate Release

Victoria B.C. – Andrew Weaver, MLA for Oak Bay Gordon Head and Deputy Leader of the B.C. Green Party, and Vicki Huntington, Independent MLA for Delta South, are profoundly concerned that Bill 12: the Federal Port Development Act will fail to safeguard environmental protections that are facing federal deregulation.

Bill 12 is the provincial link to the federal omnibus Bill C-43, which has been criticised for dismantling environmental protections on port lands through its changes to the Canada Marine Act.

“With the introduction of this bill the province is complacent in the deregulation of environmental protection,” says Andrew Weaver. “As MLAs we need more time to examine the bill.”

“This bill is triggered by Bill C-43, which places secret and extra parliamentary law-making authority in the hands of ports, provinces and even industry,” says Vicki Huntington.

Bill 12 allows the provincial government to enter into the agreements outlined in the federal bill C-43. These agreements could give the province widespread authority over ports. However, Bill 12 does nothing to address the significant environmental regulatory gaps critics say have been created by the C-43 updates to the Canada Marine Act.

For example, Bill C-43 would allow the federal government to sell federal port lands to industry. In doing so, that area would lose its status as federal land, and potentially also become exempt from terrestrial species protection under the Species At Risk Act. Bill 12 may allow LNG ports to take advantage of these loopholes.

“If the Federal government is trying to limit the environmental regulations that apply on port lands, it is up to the provincial government to ensure that adequate protection remains – we want to be sure that this Bill is doing enough on that front,” says Weaver.

MLA Weaver and MLA Huntington each introduced separate amendments designed to provide greater scrutiny of Bill 12.

-30-

West Coast Environmental Law Backgrounder

Media Contacts

Mat Wright — Press Secretary – Andrew Weaver MLA

Cell: 250 216 3382

Mat.wright@leg.bc.c

Aldous Sperl – Vicki Huntington MLA

250-952-7596

Aldous.sperl@leg.bc.ca

Bill 2 — BC Transportation Financing Authority Transit Assets and Liabilities Act

On Monday I rose to speak at second reading in support of Bill 2-2015 BC Transportation Financing Authority Transit Assets and Liabilities Act.

Currently in Vancouver, the rapid transit assets owned by the province are split between three crown corporations.

- The Expo Line and the West Coast Express is held by B.C. Transit

- The Millennium Line is held by Rapid Transit Project 2000 Ltd.

- The Evergreen line is held by B.C. Transportation Financing Authority

Bill 2 would consolidate all these assets under the BC Transportation Financing Authority while maintaining the level of service. This would allow for streamlining, cost saving and better management. While this bill helps to cut down on bureaucratic clutter, it does not deal with the larger issues facing transit in Metro Vancouver.

Below is the text of my contribution to the debate.

My contribution to the debate at second reading

I rise to speak just briefly at second reading of this bill to outline an issue that I think may have been overlooked over this bill. As the bill notes, there are currently…. These rapid transit assets owned by the province are split amongst three Crown corporations in the area: Expo Line and the West Coast Express held by B.C. Transit, the Millennium Line held by Rapid Transit Project 2000 Ltd. and the Evergreen line held by B.C. Transportation Financing Authority. Bill 2 would consolidate these into one entity while maintaining the level of service.

Now, it’s hard to argue that consolidation of assets spread around three is not actually a good thing. It would streamline administration, provide cost savings and, presumably, better management of the whole system at all. These assets, of course, would be transferred into and operated by TransLink.

Cutting down the bureaucratic clutter in the region of Metro Vancouver, I would argue, is a good thing. Nobody quite knows who is on second base at times or first base at times with the plethora of these Crown corporations with their different jurisdictions.

But here is the problem. TransLink has lost the support of the public. Nowhere is this more true than seeing the discussions happening with respect to the upcoming plebiscite in Vancouver.

This no longer becoming a question of: should Vancouver have transport or not? This is not a question of: is the PST increase a means and ways of funding the transit improvements in Vancouver? What’s happening in Vancouver is that this plebiscite is becoming a plebiscite on TransLink, and that is most unfortunate.

That’s most unfortunate because here in this bill we have bringing together assets into a Crown corporation that has lost the public trust. In doing so, the public will question the rationale behind this. The public will question whether or not bringing in TransLink is the right thing to do. The public will question whether or not this is actually going to improve service.

Accountability is the keystone — and was the keystone — of the original vision of TransLink. It was envisioned as a regional authority to be run by a local and elected board. But now, of course, it’s no longer the case. We have an appointed board. We have an appointed board which is not accountable to the voters. The council of mayors, which makes recommendations and have to live with the consequences of decisions being made, is elected. But they don’t actually have the control over the process and decision-making.

This bill is bringing more assets into an organization, TransLink, a Crown corporation that will have more control and more voice over what the mayors must implement, at the same time as it’s losing the confidence of the general public. In order to deal with the root cause, the root problem, that exists — that is, the lack of public support for TransLink — we’ll need to explore, in committee stage, how the government plans to actually assure us that as it brings more and more assets into the Crown corporation for transit, it does so in means and ways that do not ignore the underlying fundamental issue, which is rebuilding public trust and public confidence in TransLink.

Vancouver’s Transit Referendum — A synopsis

In the coming weeks, hundreds of thousands of ballots will be mailed out across Metro Vancouver asking residents a simple question:

“Do you support a new 0.5% Metro Vancouver Congestion Improvement Tax, to be dedicated to the Mayors’ Transportation and Transit Plan? Yes or No.“

If I lived in Vancouver, I would vote ‘Yes’. I would do so reluctantly. I would do so begrudgingly. And I would do so frustratedly, knowing that my provincial government had abdicated its leadership responsibility. Yet I would hope with all sincerity for a ‘Yes’ victory.

Vancouver is Canada’s most congested city and the third most congested city in North America, behind Los Angeles and Mexico City. As noted in a recent story by Ian Bailey in the Globe and Mail , “the average Vancouver driver experiences 87 hours of delay time a year based on a 30-minute daily commute.” With a population of more than 2.5 million and growing, it is without doubt that Metro Vancouver needs to make substantial investments in improving its public transportation.

The Problem with the Referendum

But let’s be very clear. This referendum is a waste of taxpayers’ money and demonstrates an appalling lack of leadership by the Liberal Government. The province is abdicating its responsibility to govern and the level of inconsistency being displayed is truly mind boggling. This same government has no problem announcing high-profile ribbon-cutting opportunities like replacing the Massey Tunnel with a bridge or adding a second bridge across Okanagan Lake without even a hint of a referendum. So why are we having one now?

That this government would hamstring Metro Vancouver Mayors with a referendum on new funding for transit infrastructure—a policy that both the government and the official opposition support—is unconscionable.

In my opinion we are left with two fundamental and unanswered questions:

- Why are we having a referendum on a policy when both the Government and Official Opposition, as well as business groups and other stakeholders, all agree that new funding is required to address congestion in the Lower Mainland?

- If we go through with a referendum and it gets voted down, what is the Plan B for the BC Liberals to address the transportation issues facing our largest population centres?

In the Spring of 2014, when the government introduced Bill 23 — South Coast British Columbia Transportation Authority Funding Referenda Act, the BC NDP spoke passionately against the bill. They argued, like I do above, that the government should show leadership and empower the Mayors Council to move forward with their transportation plans. They also pointed out that there were no details about any back up plan in case the referendum failed.

More recently the Premier has suggested that the Mayor’s could use Property Tax hikes to fund transit improvements if the referendum failed. In my opinion, this is the greatest abdication of responsibility we have seen so far. To reject Mayors’ initial strategy to raise funds, to then force a referendum on them that the Mayors didn’t want, and then to suggest that it is the Mayors’ responsibility to find the funding if the referendum fails, is indicative of a provincial government that is lacking leadership and doing all it can to avoid taking responsibility.

An Alternative Approach

So what do I think we should be doing?

During the election I campaigned on increasing the carbon levy by $5 per year until it hits $50/tonne, at which point we could assess where we are at. Currently, the carbon levy is revenue neutral; all of the revenue collected is subsequently returned to the economy through personal income tax and small business tax credits. But it doesn’t have to be that way going forward. For example, Quebec used their carbon levy revenue to improve public infrastructure.

During the election campaign I argued that Municipalities across British Columbia are facing an infrastructure deficit. Our public infrastructure (roads, sewers, bridges etc) was built last century. It is now old and crumbling and increasingly strained as our population grows.

Property tax increases are becoming unbearable for many, particularly seniors on fixed-income. Deferring property tax payments into the future doesn’t deal with the problem today. So I argued that during the next phase of the carbon levy increase (the next four years) all monies could be returned to municipalities to support them to deal with their infrastructure deficits, including public transportation.

By steadily increasing emissions pricing, we send a signal to the market that incentivises innovation and the transition to a low carbon economy. The funding transferred to municipalities across the province provides them with resources to deal with their aging infrastructure and growing transportation issues. By investing in the replacement of aging infrastructure in communities throughout the province we stimulate local economies and create jobs.

And importantly, by moving to this polluter-pays model of revenue generation for municipalities, we reduce the burden on regressive property taxes. Done right, this model could lead to municipalities actually reducing property taxes, thereby benefitting homeowners, fixed-income seniors, landlords and their tenants.

What better time to do this than now, with the price of oil hovering at $50/barrel. Most businesses would have already budgeted for a much higher price for oil. And the beauty of this approach is that as revenues from emissions pricing go down, direct revenues from public transport go up as more people move from single passenger vehicles to the skytrain.

While I recognize it may be too late to cancel the referendum, it’s time that we start having a more open and honest discussion about our aging infrastructure, the requirements for public transport and the means of generating revenue to pay for them.