Uncategorized

Advancing nature based climate solutions: a cautionary tale

In recent years, governments and industry have become more and more interested in supporting so-called nature based climate solutions. So what are such solutions? The Nature Conservancy provides a concise definition: Nature-based climate solutions “are actions to protect, better manage and restore nature to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and store carbon.”

Such solutions aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions (mitigation) fall into two categories: 1) those that the enhance the uptake and storage of carbon within natural ecosystem; 2) those that reduce the emissions of greenhouse gases (e.g., carbon dioxide and methane) from natural ecosystems.

While the above definition recognizes the link between natural ecosystems and the global carbon cycle, nature based solutions also play a critical role in climate change adaptation strategies. A more complete definition that includes both their roles has been offered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and subsequently used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

“Nature-based Solutions are actions to protect, sustainably manage, and restore natural and modified ecosystems that address societal challenges effectively and adaptively, simultaneously benefiting people and nature.“

Below I attempt to highlight the important role that such solutions play in both climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies. But I try to put such solutions in the bigger context of what needs to be done to meet the challenge of global warming. I’ll attempt to outline why governments and industry appear to be so supportive of such solutions, yet point out the danger of over-relying on them.

To be clear, nature-based climate solutions have a crucial role to play. Cumulative anthropogenic fossil carbon emissions from 1750 to 2021 have been 474 GtC (billions of tons of carbon), while deforestation and land use changes have contributed another 203 GtC. That is, anthropogenic disruption of natural ecosystems has accounted for about 30% of historical greenhouse gas emissions, so it seems reasonable to expect nature-based climate solutions to have an important role to play moving forward. But there are limits. In fact, a recent paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggested that nature-based solutions could be used to meet 20% of the required emission reductions to be implemented prior to 2050 to keep global warming to below 2°C. I’ve pointed out for years (and summarized these views again recently), that the 1.5°C target was not attainable even when proposed in the 2015 Paris Accord, due to socioeconomic inertia in our built environment, the role of atmospheric aerosols, and potential effects from the permafrost carbon feedback.

Examples of Nature Based Climate Solutions

To start, I thought it would be illustrative to provide a few examples of nature based climate solutions in action. This list is by no means comprehensive, but rather serves solely to give the reader a sense of what such solutions entail.

The most obvious example of a nature based solution is planting trees. Widespread deforestation, particularly in the creation of pastures for cattle grazing and land for farming or other human uses, has provided the lion’s share of the historical 203 GtC released to the atmosphere. Reforestation (planting trees where they once were) and afforestation (planting trees in places where they weren’t historically present) both have the potential to draw carbon from they atmosphere as they grow. But of course, if we want to use tree planting in carbon budget accounting, we would also have keep track of the carbon released during forest fires.

The most obvious example of a nature based solution is planting trees. Widespread deforestation, particularly in the creation of pastures for cattle grazing and land for farming or other human uses, has provided the lion’s share of the historical 203 GtC released to the atmosphere. Reforestation (planting trees where they once were) and afforestation (planting trees in places where they weren’t historically present) both have the potential to draw carbon from they atmosphere as they grow. But of course, if we want to use tree planting in carbon budget accounting, we would also have keep track of the carbon released during forest fires.

Urban planners also incorporate tree management in their climate adaptation strategies. For example, they recognize that increasing the tree canopy can help keep cities cooler in the summer than they would otherwise be. Homeowners, for example, might plant deciduous trees in their front yard that blocks the sun from their main windows in the summer, but allow the sunshine in during the late fall and winter once the leaves have fallen.

The use of biochar to enhance the properties of soil has also been proposed as a potential nature-based climate solution. Biochar (a charcoal like substance) is created through a process known as biomass pyrolysis. (high temperature decomposition of plant material). The addition of biochar to agricultural soil leads to enhanced soil carbon uptake and storage, reduced requirement for fertilizer use (and hence reduced nitrous oxide emissions), and improved water use efficiency. Other agricultural nature-based solutions involving tiling practices, crop/grazing rotations, cover crops etc. have also been proposed.

The use of biochar to enhance the properties of soil has also been proposed as a potential nature-based climate solution. Biochar (a charcoal like substance) is created through a process known as biomass pyrolysis. (high temperature decomposition of plant material). The addition of biochar to agricultural soil leads to enhanced soil carbon uptake and storage, reduced requirement for fertilizer use (and hence reduced nitrous oxide emissions), and improved water use efficiency. Other agricultural nature-based solutions involving tiling practices, crop/grazing rotations, cover crops etc. have also been proposed.

In the coastal ocean, mangroves, salt marshes and seagrass meadows more efficiently capture and store carbon than land based, slow-growing forests. Many of these so called “blue carbon” sinks have been stressed by human activity in research decades and steps have been taken to both preserve and enhance their health and extent. These rich, biodiverse ecosystems also play key roles in climate change adaptation as they serve to protect coastal erosion from storms and sea level rise.

In the coastal ocean, mangroves, salt marshes and seagrass meadows more efficiently capture and store carbon than land based, slow-growing forests. Many of these so called “blue carbon” sinks have been stressed by human activity in research decades and steps have been taken to both preserve and enhance their health and extent. These rich, biodiverse ecosystems also play key roles in climate change adaptation as they serve to protect coastal erosion from storms and sea level rise.

Recognizing the importance of nature-based solutions, the Canadian federal government developed a natural climate solutions fund to protect, enhance and preserves Canada’s biodiverse and carbon rich wetlands, grasslands and forests, in addition to a commitment to plant two billion trees over a ten-year period.

What’s required to stabilize atmospheric temperature

As most everyone is aware, the goal of the internationally-negotiated Paris Agreement is to limit global warming to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels while pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C. Yet we’ve known for more than 15 years that such a target would ultimately require rapid decarbonization and the introduction and scale-up of negative emission technology. In a paper entitled Long term climate implications of 2050 reduction targets that we published in 2007, we note in the abstract (and discussed below):

“Our results suggest that if a 2.0°C warming is to be avoided, direct CO2 capture from the air, together with subsequent sequestration, would eventually have to be introduced in addition to sustained 90% global carbon emissions reductions by 2050.“

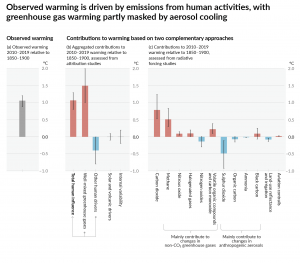

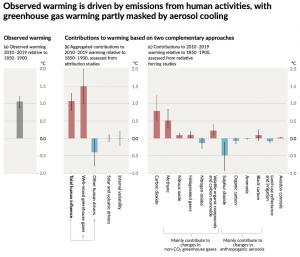

Earth has already warmed by ~1.1-1.2 °C since preindustrial times and if worldwide fossil fuel combustion was immediately eliminated, the direct and indirect net cooling effect of atmospheric aerosol loading would rapidly dissipate through gravitational settling and precipitation scavenging of these aerosols. As such, the source of the ~0.5 °C aerosol cooling realized since the preindustrial era would be eliminated (see Figure 1), thereby taking the Earth rapidly to ~1.6-1.7 °C warming. The Earth would warm further as we equilibrate to the present 523 ppm CO2e (NOAA 2023) greenhouse gas loading in the atmosphere (only 417 ppm of which is associated with CO2), and that is not including the committed warming from the permafrost carbon feedback that would add another 0.1 to 0.2 °C this century (Macdougall et al, 2013).

Figure 1: Observed global warming (2010-2019 relative to 1850-1900) and the contribution to this net warming by observed changes to natural and anthropogenic radiative forcing. Reproduced from IPCC (2021).

Let’s once more explore the level of decarbonization required to keep warming below 2°C (recognizing that 1.5°C is no longer attainable). I present results from the UVic Earth System Climate model discussed in Weaver et al. (2007) and my book Keeping our Cool: Canada in a Warming World.

Starting from a pre-industrial equilibrium climate, I force the UVic model with observed natural and human-caused radiative forcing until the end of 2005. After 2005, future trajectories in emissions must be specified. Each of the post-2005 scenarios I use assumes that contributions to radiative forcing from sulphate aerosols and greenhouse gases other than carbon dioxide remained fixed throughout the simulations. An alternative way of looking at this is that any increase in human- produced, non-carbon dioxide greenhouse gases is assumed to be balanced by an increase in sulphate aerosols (or some other negative radiative forcing). This assumption should be viewed as extremely conservative, since most future emissions scenarios have decreasing sulphate emissions and increasing emissions of non-carbon dioxide greenhouse gases.

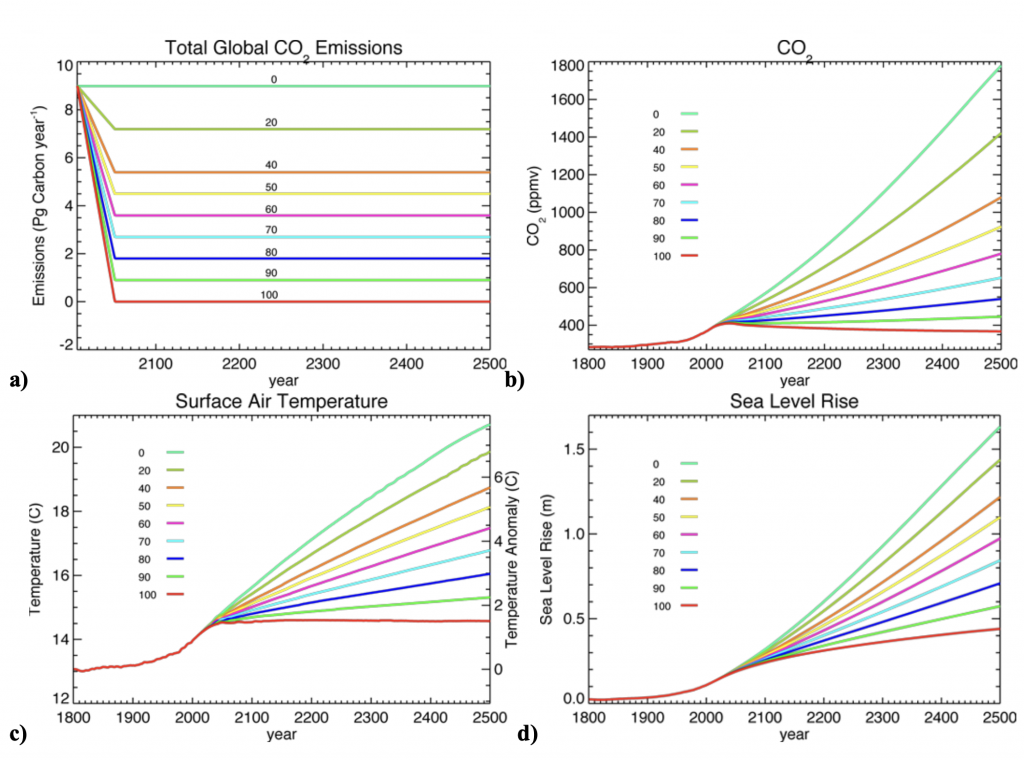

We’ll start by examining the effects of a hypothetical international policy option that linearly cuts emissions by some percentage of 2006 levels by 2050, and maintains emissions constant thereafter until the year 2500 (see Figure 2a). Of course, my baseline case of constant 2006 emissions is substantially more optimistic than the IPCC scenarios, some of which have 2050 emissions at more than double 2006 levels. The various pathways in emissions lead to atmospheric carbon dioxide levels in 2050 ranging from 407 ppm to 466 ppm, corresponding to warming relative to 1800 of between 1.5°C and 1.8°C (Figure 2b and Figure 2c). As the twenty-first century progresses, the atmospheric carbon dioxide levels and warming begin to diverge between scenarios, and by 2100 the range is 394 ppm to 570 ppm (we are presently at 417 ppm), with a warming of between 1.5°C and 2.6°C. None of the emissions trajectories lead to an equilibrium climate and carbon cycle in 2500, although the 90% and 100% sustained 2050 emissions reductions have atmospheric carbon dioxide levels that are levelling off. Of particular note is that by 2500, the scenario depicting a 100% reduction in emissions leads to an atmospheric carbon dioxide level below that in 2006, although global mean surface air temperature is still 0.5°C warmer than in 2006 (1.5°C warmer than 1800). While this version of the UVic Earth System Model only calculates the thermal expansion component of seal level rise and ignores contributions from glacier and ice sheet melt, the results shown in Figure 2d indicate that sea level rise still has not equilibrated even after 500 years.  Figure 2: (a) Observed anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions from 1800 to 2006 (red) followed by linear reductions of 0–100% of 2006 levels by 2050. From 2050 onwards emissions are held constant. Transient evolution of globally-averaged (b) atmospheric carbon dioxide, (c) surface air temperature, and (d) sea level rise due to thermal expansion for all experiments. Note that the sea-level curves have no contribution from the melting of land-based ice.

Figure 2: (a) Observed anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions from 1800 to 2006 (red) followed by linear reductions of 0–100% of 2006 levels by 2050. From 2050 onwards emissions are held constant. Transient evolution of globally-averaged (b) atmospheric carbon dioxide, (c) surface air temperature, and (d) sea level rise due to thermal expansion for all experiments. Note that the sea-level curves have no contribution from the melting of land-based ice.

All simulations that have less than a 60% reduction in global emissions by 2050 eventually break the threshold of 2°C warming this century. Even if emissions are eventually stabilized at 90% less than 2006 levels globally (1.1 billions of tonnes of carbon emitted per year), the 2°C threshold warming limit is eventually broken well before the year 2500. This implies that if a 2°C warming is to be avoided, direct CO2 capture from the air, together with subsequent sequestration, would eventually have to be introduced in addition to 90% reductions in global carbon emissions.

I purposely kept emissions constant after 2050 in my idealized scenarios to illustrate that cutting emissions by some prescribed amount by 2050 is in and of itself not sufficient to deal with the problem of global warming. Even if we maintain global carbon dioxide emissions at 90% below current levels, we eventually break the 2°C threshold. This is because the natural carbon dioxide removal processes can’t work fast enough to take up the emissions we emit to the atmosphere year after year. Any solution to global warming will ultimately require the world to move towards net zero emissions carbon which requires the introduction and global scale up of negative emission technology.

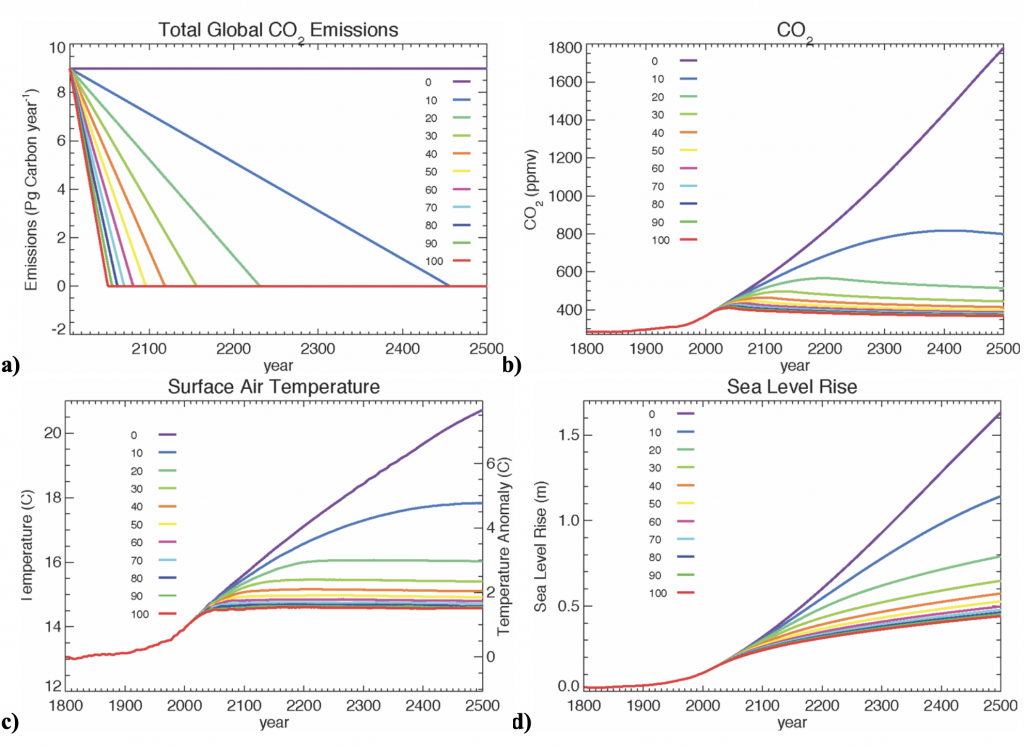

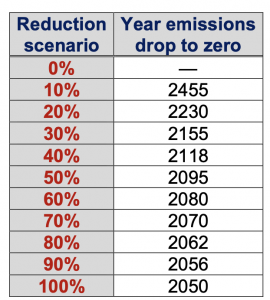

Figure 3: As in Figure 2 but the emissions in (a) continue the linear decrease until zero emissions are reached. The year in which zero emissions is reached is indicated in the table below.

Now let’s examine the effects of another hypothetical international policy option that starts from the results obtained in the previous suite of experiments at 2050 but now continues to linearly decrease emissions at the same rate until zero emissions are reached. The resulting emissions are shown in Figure 3a and the date at which emissions fall to zero is given in table to the right.

Now let’s examine the effects of another hypothetical international policy option that starts from the results obtained in the previous suite of experiments at 2050 but now continues to linearly decrease emissions at the same rate until zero emissions are reached. The resulting emissions are shown in Figure 3a and the date at which emissions fall to zero is given in table to the right.

If we keep emissions on a linearly decreasing emissions path to carbon neutrality, it turns out that in the UVic model about 45% or larger reductions (relative to 2005 levels) are required by 2050 if we do not wish to break the 2°C threshold. And peak atmospheric carbon dioxide levels reach a little over 450 ppm before settling down to slightly above 400 ppm. Notice that in all cases, even though emissions have gone to zero, sea level continues to rise. It’s further important to note that these simulations were conducted and published in 2007 and assumed the hypothetical scenario of an immediate curtailing of emissions. The reality is global fossil carbon emissions (excluding land use emissions) were 10.1 GtC (billions of tonnes of carbon) in 2021 which is a 25% increase from 2005 levels (when they were 8.1GtC).

In this section I have tried to emphasize that the only means of stabilizing the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is for humanity to achieve net zero carbon emissions. While the implementation of nature-based solutions provides some additional time before net zero must be reached to avoid breaking the 2°C guardrail, there is a danger that such efforts are being overly promoted by governments and industry to allow them to maintain the status quo of oil, gas and coal exploration and combustion.

It’s a question of timescale

Millions of years ago when the atmosphere had much higher concentrations of carbon dioxide, trees, ferns, and other plants were abundant. These plants used the sun’s energy, together with carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and water, to create glucose or sugar and release oxygen back to the atmosphere (photosynthesis). As the years went by, plants would grow and die, and some of these dead trees and other vegetation would fall into swampy waters depleted in oxygen. In this environment, the organic matter only partially decayed and so turned into peat, a precursor for coal formation. Over time, shallow seas covered some of the swampy regions, depositing layers of mud or silt. As the pressure started to increase, the peat was transformed, over millions of years, into brown coal, then soft coal, and finally hard coal.

Millions of years ago when the atmosphere had much higher concentrations of carbon dioxide, trees, ferns, and other plants were abundant. These plants used the sun’s energy, together with carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and water, to create glucose or sugar and release oxygen back to the atmosphere (photosynthesis). As the years went by, plants would grow and die, and some of these dead trees and other vegetation would fall into swampy waters depleted in oxygen. In this environment, the organic matter only partially decayed and so turned into peat, a precursor for coal formation. Over time, shallow seas covered some of the swampy regions, depositing layers of mud or silt. As the pressure started to increase, the peat was transformed, over millions of years, into brown coal, then soft coal, and finally hard coal.

A similar process occurred within shallow seas where ocean plants (e.g., phytoplankton) and marine creatures would die and sink to the bottom to be buried in the sediments below. Over millions of years, the sediments hardened to produce sedimentary rocks, and the resulting high pressures and temperatures caused the organic matter to transform slowly into oil or natural gas. The great oil and natural gas reserves of today formed in these ancient sedimentary basins.

Today when we burn a fossil fuel, we are harvesting the sun’s energy stored from millions of years ago. In the process, we are also releasing the carbon dioxide that had been drawn out of that ancient atmosphere (which had much higher levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere than today). So, unless we can actually figure out a way to speed up the millions of years required to sequester carbon from the atmosphere and to convert dead plants back into peat and then coal (or oil and gas) the idea that we can somehow stop global warming solely through nature-based solutions isn’t realistic.

Nevertheless, and I reiterate, there are many positive reasons for planting new forests (afforestation), replanting old forests (reforestation), or reducing the destruction of existing forests (deforestation), including the restoration of natural habitat and the prevention of loss of biodiversity. However, trees only store carbon over the course of their lifetime. When these trees die, or if they burn, the carbon is released back to the atmosphere.

The danger of over reliance on nature based solutions

While nature-based solutions have an important role to play in climate change adaptation and the preservation of biodiversity, there is a growing danger that governments, industry and the general public will come to rely on them as a means to maintain the status quo.

Let’s take British Columbia’s LNG experience as an example.

In the lead up the the 2013 provincial election I repeatedly pointed out the economic and environmental folly of somehow believing that BC would build prosperity through liquifying natural gas and shipping it to Asia. In fact, I quantified my concerns in one of the first blog posts I wrote in the BC Legislature. British Columbia residents were being told that at least five major LNG facilities would be built in BC by 2020. Today we have none, so I would suggest that my concerns about the economics of LNG were spot on.

In the lead up the the 2013 provincial election I repeatedly pointed out the economic and environmental folly of somehow believing that BC would build prosperity through liquifying natural gas and shipping it to Asia. In fact, I quantified my concerns in one of the first blog posts I wrote in the BC Legislature. British Columbia residents were being told that at least five major LNG facilities would be built in BC by 2020. Today we have none, so I would suggest that my concerns about the economics of LNG were spot on.

In 2018, when it was clear that BC’s plans for LNG were not going to materialize, the BC NDP picked up where the BC Liberals left off and further sweetened the tax credit regime for LNG Canada, the one remaining major LNG company left in BC. It was clear to me that British Columbia could not meet its legislated greenhouse gas reduction targets if the LNG Canada project was ever built and I wrote a detailed blog post pointing out that it was time for both the BC NDP and the BC Liberals to level with British Columbians about LNG. The BC NDP government remained adamant that BC could still reduce emissions to 40% below 2007 levels by 2030. I remained skeptical and feared that this target can only be achieved through creative carbon accounting and appealing to “nature-based solutions”. I believe I was and remain correct. The analysis above and my earlier blog posts should make that obvious. And nobody should be surprised to see Shell Canada now promoting its efforts to ensure “the protection and restoration of natural ecosystems such as forests, grasslands and wetlands” as a central component to its greenhouse gas mitigation strategy. Of course, there is no mention of greenhouse gas emissions from the ever increasing area burnt by Canadian wildfires, nor the emissions being triggered as permafrost thaws and the previously frozen organic matter begins to decompose.

The Darkwoods Forest Carbon project offers a glimpse into what is likely being considered by BC government and industry decision-makers as a means of offsetting emissions from the natural gas sector. The problem with this is threefold.

First, claiming that the preservation of a forest should be considered a carbon offset using an argument that the wood would otherwise be harvested is a bit like me say to you: “give me $10,000 or I will buy a gas-guzzling SUV”! Second, if you want to claim a carbon credit for planting a tree, then you have to also accept a debit if that tree, or another, burns down. Third, their is no international mechanism to get credit for such a nature-based offset and these are purely considered voluntary.

Summary

In this post I have tried to outline the important role that nature-based climate solutions play amid the suite of policy options available to government and industry. The cautionary tale is that while these represent important contributions to a jurisdiction’s overall climate change adaptation and mitigation strategy, they cannot take away from the requirement to decarbonize energy systems immediately. As outlined in a recent article published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B by researchers from Oxford University in the UK, “there are concerns over their reliability and cost-effectiveness compared to engineered alternatives, and their resilience to climate change.”

For years I have noted that the signing of the Paris Agreement in 2015 had immediate consequences for oil, gas and coal exploration. At the time of its signing, and given the availability of existing technologies, the Paris Agreement translated to the notion that effective immediately, no new oil, gas or coal infrastructure could be built anywhere in the world if we want to keep warming to below 2°C. This follows since such major capital investments have a long payback time; you don’t build a natural gas electricity plant today only to tear it down tomorrow. Socioeconomic inertia in the built environment also suggests that the capital stock turnover time would be decades, not years.

Nature based-solutions are really a natural branch of other so-called Carbon Dioxide Removal geoengineering projects. Another solution that has received some attention of late concerns increasing the alkalinity of surface waters through dissolution of limestone. This geo-engineering fix was one of many examined by the IPCC in a 2005 special report assessing the possibility of capturing and storing carbon dioxide. To sequester 1 kilogram of carbon dioxide without the negative effects associated with acidification 3.5 kilograms of calcium carbonate (limestone) would have to be artificially dissolved in the ocean. Today, about 6.6 Gt of limestone is mined annually. If the entirety of this global production was dissolved in the ocean, about 1.9 Gt of carbon dioxide could be sequestered annually (or 0.5 Gt of carbon equivalent). This represents about 5% of the world’s 2021 global carbon dioxide emissions. A twenty-fold increase in limestone mining to sequester our present-day emissions would have enormous energy implications (with their concomitant emissions), not to mention the potential environmental impacts of such expanded mining activities. We would also have to stop producing cement, which uses this limestone, throughout the world, meaning that concrete could no longer be used in construction. It should be clear that attempting to modify surface alkalinity using the world’s limestone resources is not a serious proposition to combat global warming.

Nature based-solutions are really a natural branch of other so-called Carbon Dioxide Removal geoengineering projects. Another solution that has received some attention of late concerns increasing the alkalinity of surface waters through dissolution of limestone. This geo-engineering fix was one of many examined by the IPCC in a 2005 special report assessing the possibility of capturing and storing carbon dioxide. To sequester 1 kilogram of carbon dioxide without the negative effects associated with acidification 3.5 kilograms of calcium carbonate (limestone) would have to be artificially dissolved in the ocean. Today, about 6.6 Gt of limestone is mined annually. If the entirety of this global production was dissolved in the ocean, about 1.9 Gt of carbon dioxide could be sequestered annually (or 0.5 Gt of carbon equivalent). This represents about 5% of the world’s 2021 global carbon dioxide emissions. A twenty-fold increase in limestone mining to sequester our present-day emissions would have enormous energy implications (with their concomitant emissions), not to mention the potential environmental impacts of such expanded mining activities. We would also have to stop producing cement, which uses this limestone, throughout the world, meaning that concrete could no longer be used in construction. It should be clear that attempting to modify surface alkalinity using the world’s limestone resources is not a serious proposition to combat global warming.

So in summary, despite the many benefits of nature-based solutions, what is required to keep global warming to below 2°C (or, frankly, to stabilize it at any level), is the immediate transition towards the decardonization of global energy systems along with the widespread introduction of negative emission technology, such as direct air carbon capture and deep underground storage. At this stage, I am of the belief that this remains the only hope humanity has for a long term solution to this problem. We can take comfort in the very real successes of nature-based solutions, and their many co-benefits, but we cannot take our eyes off the scale of the challenge before us. Fortunately, all the solutions are known. It is a matter of individual, institutional, corporate and political will as to whether or not we will achieve the goals of net zero emissions in the future.

Thoughtful voices: Sacha Christensen, Mark Leiren-Young & Rishi Sharma

In 2012, as I started my journey to become the BC Green MLA for Oak Bay Gordon Head, I was only too aware of how difficult it would be to win against the incumbent, BC Liberal Ida Chong. I was running for a party that had never elected anyone at the provincial level anywhere in Canada. There were no “party lists” that we could draw from; there was no party “apparatus” to call upon; there was no real “election readiness” or “provincial strategy”. Each of the BC Green candidates had to organically grow their support from the bottom up. And we did so against difficult odds and without access to organization networks like those associated with the so-called BC NDP ground game. I believed that the pathway to victory involved vowing to do politics differently and promising to work with whomever formed government. Ultimately, this approach was successful and I was able to advance numerous bills working collaboratively with the BC Liberals (from 2013-2017) and then the BC NDP (from 2017-2020).

When we elect politicians to govern on our behalf, we are electing individuals who are each armed with a toolkit of life skills, experiences, qualifications and views. Ideally, each elected person has a complementary, rather than identical, set of tools in their tool kits. For when these complementary tools are spread out on the decision-making table, more creative, inclusive and thoughtful policy and solutions are built. But in my view, what is most important is that we elect individuals who recognize the importance of advancing lasting policy through good governance that transcends traditional partisan divides.

On October 15, we go to the polls in the next general local elections. While I have already voted in an advanced poll for a full and diverse slate of School Board and Council candidates, I wanted to highlight three remarkable individuals on my list. These individuals span the political spectrum, and exemplify what I look for in an elected leader. None of them are presently holding elected office and there are enough incumbents not running to ensure that new people must be at the Saanich Council and School District 61 Board tables. I provide my rationale as to why I voted for these three individuals to help others as they do their research on who they will support on October 15. I recognize the importance of name recognition in local government elections and perhaps by doing this, I might convince a few of you to reach out to the three candidates below to learn more about their compelling campaigns.

1) Sacha Christensen – candidate for SD61 Trustee.

Despite the apparent lack of attention given to school board elections, Trustees in School District 61 actually manage a bigger budget ($268 million for 2022-23) than do the Mayor and Council of Saanich ($222 million for 2022-23). Over the past year, School District 61 was rocked with controversy as two trustees were suspended and subsequently reinstated. The annual budget process was also not without its own public controversy as music and support services took a hit to make ends meet. Given the turbulence of the past year, and with Board Chair Ryan Painter, Angie Hentze, and long time Trustees Elaine Leonard and Tom Ferris not seeking reelection, it is important to elect individuals with demonstrated expertise and experience who understand the importance of a collaborative, as opposed to an adversarial, approach to good governance.

Despite the apparent lack of attention given to school board elections, Trustees in School District 61 actually manage a bigger budget ($268 million for 2022-23) than do the Mayor and Council of Saanich ($222 million for 2022-23). Over the past year, School District 61 was rocked with controversy as two trustees were suspended and subsequently reinstated. The annual budget process was also not without its own public controversy as music and support services took a hit to make ends meet. Given the turbulence of the past year, and with Board Chair Ryan Painter, Angie Hentze, and long time Trustees Elaine Leonard and Tom Ferris not seeking reelection, it is important to elect individuals with demonstrated expertise and experience who understand the importance of a collaborative, as opposed to an adversarial, approach to good governance.

After being told by one of my children that I should consider voting for Sacha, I decided to interview him to learn more about why he was running to be a School Board Trustee at the age of 24. I was extremely impressed by his maturity, thoughtfulness and profound insight into civic and school politics.

Sacha graduated from the challenge program at Esquimalt High School and has completed his first two years of political science at Camosun College. For the past three years he has been working as the constituency assistant in Randall Garrison’s MP office. Constituency assistants play a critical non partisan role in an MP or MLA office. They are the front line staff who interact with and help constituents access the services available to them. As such, they are the public face of an MP or MLA in many community interactions. They should be unconditionally ethical and trustworthy, articulate, have exemplary interpersonal communication skills, hard working, intelligent and empathetic. It became quickly obvious to me why Randal Garrison had hired Sacha.

I asked Sacha why he chose to run to become a Trustee. He pointed out that the present make up of the Board was closer to retirement than to being back in school and that he felt it was critical to ensure students were always front and centre in School Board decision-making. He expressed concern over the 49% 5-year (57% 6-year) indigenous graduation rate in the district and the emergence of the VIVA slate of candidates who he did not believe shared his values. We talked about the lack of funding for students with diverse abilities and the troubling provincial model of education funding. I came away with the impression that Sacha was an exceptionally pragmatic thinker who understands how to advance policy solutions by bringing people together.

In summary, I am very impressed with Sacha Christensen’s collaborative approach to politics, as well as his perspective as a young candidate. I believe he has the expertise and experience to restore good governance to our school board.

More information on Sacha Christensen’s quest to become a Trustee in School District 62 is available on his campaign website.

2) Mark Leiren-Young — candidate for Saanich Council

I first met Mark many years ago when he came to interview me at my office at the University of Victoria. Mark was doing a podcast series on trees and I had just completed my book: Generation Us – The Challenge of Global Warming. We hit it off right away.

I first met Mark many years ago when he came to interview me at my office at the University of Victoria. Mark was doing a podcast series on trees and I had just completed my book: Generation Us – The Challenge of Global Warming. We hit it off right away.

A few years later, I once more bumped into Mark on the set of Wes Borg’s live comedy show, Derwin Blanshard’s Extremely Classy Sunday Evening Program, a show that I had become a regular on before I got elected. He sang “Kumbaya” as I proceeded to “beat the character of an Irish ambassador to Canada“, who was cast as a rabid climate change denier on the show, with a large “Nobel prize” prop! It was good-natured humour and Mark and I saw each other in different lights! It was also the last show I did before getting elected! And then in 2017, Mark interviewed me again in the final days of the 2017 provincial election campaign just prior to our historic election result, wherein the BC Greens were afforded the balance of power in the 2017-2020 BC NDP minority government.

Mark has been surrounded by politics his entire life. His mother met his father when she was running for Vancouver City Council and he was covering it for The Vancouver Sun. His father went on to become the legislative reporter for The Sun and then Bill Bennett’s press secretary. Mark also covered politics as a journalist for years and – among other gigs – used to write for a magazine called Trade and Commerce where he helped translate municipal business plans into plain language to draw businesses and investors to municipalities throughout the lower mainland. He was approached about becoming the city hall columnist for a couple of Vancouver’s better media outlets. And he started writing for the Monday Magazine while he was still a UVic student.

Mark is an exceptionally gifted artist and communicator. He’s won numerous awards for his books, television, theatre and film productions and teaches in University of Victoria’s creative writing department. Virtually all of his work, including some of my his commercial work, has involved social or environmental themes. Mark is creative, collaborative, innovative, pragmatic and understands how to work across partisan divides to advance inclusive policy for our community.

More information on Mark Leiren-Young’s quest to become a Saanich Councillor is available on his campaign website.

3) Rishi Sharma — candidate for Saanich Council

Rishi and I got to know each other in the 2013 provincial election campaign. He was the BC Liberal candidate for the riding of Saanich South and was running against my friend and colleague (from my days in the legislature), Lana Popham.

Rishi and I got to know each other in the 2013 provincial election campaign. He was the BC Liberal candidate for the riding of Saanich South and was running against my friend and colleague (from my days in the legislature), Lana Popham.

While I first met Rishi during an in-studio CFAX 1070 interview/debate early in the campaign, I got to know him better following an all candidates meeting that we we both participated in. Organized by the BC Sustainable Energy Association, this was a packed public event held at the Fernwood Community Centre on the theme: Energy and Climate. Rishi represented the BC Liberals. Rob Fleming (NDP), Duane Nickull (BC Conservatives) and I (BC Greens) were our party nominees. To no one’s surprise, the audience was not particularly warm towards the incumbent BC Liberal government. Yet it was clear to me why the BC Liberals sent Rishi to represent them. He was a compassionate listener and a thoughtful speaker.

What also struck me early on about Rishi was the respect, ethics and integrity he brought to his election campaign. We were both representing different political parties, yet we were both able to converse in a collaborative way. We focused on our shared values and spoke about how we could advance creative solutions to the issues facing the province. And over the decade since we first met, I have followed Rishi’s work within the BC Government.

What also struck me early on about Rishi was the respect, ethics and integrity he brought to his election campaign. We were both representing different political parties, yet we were both able to converse in a collaborative way. We focused on our shared values and spoke about how we could advance creative solutions to the issues facing the province. And over the decade since we first met, I have followed Rishi’s work within the BC Government.

Unlike many candidates running for local government positions, Rishi was born in, grew up in, and still lives in the community of Saanich. He attended Hillcrest Elementary, Arbutus Junior High and Mount Doug High School. His postgraduate studies include classes at UVic, Camosun and, more recently, Royal Roads university where he is finishing off his MA in Organizational Leadership. Rishi was also an accomplished athlete, playing soccer for Gordon Head, Metro Victoria and the BC Selects, while also competing in field hockey. He continues to give back to the community as a volunteer coash with Saanich Fusion soccer.

One of the things that most impresses me about Rishi is his deep insight into the needs of our community. He is pragmatic, principled, empathetic and respectful in all his work. He also brings business acumen to the decision making table.

More information on Rishi Sharma’s quest to become a Saanich Councillor is available on his campaign website.

Sustainable Aviation Fuel — Opportunities for Innovation in Aviation Sector

With the summer holiday season coming to an end, and after hearing no end of COVID-related horror stories (delays, cancelled flights, staff shortages, passport issues) from friends and family who decided to travel by air to destinations afar for the first time in several years, I thought I would spend some time exploring climate solutions in the aviation sector.

the summer holiday season coming to an end, and after hearing no end of COVID-related horror stories (delays, cancelled flights, staff shortages, passport issues) from friends and family who decided to travel by air to destinations afar for the first time in several years, I thought I would spend some time exploring climate solutions in the aviation sector.

As I noted in my recent presentation to the BC Aviation Council May Conference 2022, Transportation in the aviation sector affects our climate through two main ways. The first, and most obvious, is via the emissions of greenhouse gases associated with the combustion of jet fuel. In 2020, international (not including domestic) aviation was the 10th biggest total emitter of carbon (171.15 Megatonnes) world wide (behind China, USA, India, Russia, Japan, International Shipping, Germany, Iran and South Korea). In total, aviation accounts for about 2.5% of global emissions of carbon dioxide.

The second main way that aviation affects the climate system is through the creation of contrails. Contrails occur when moisture in jet exhaust condenses in the high altitude cold ambient environment to create lines of thin cirrus clouds, comprising ice crystals, whose net effect is to warm the Earth further. While innovation in flight path planning is ongoing in an effort to reduce contrail formation, off the shelf solutions to replace jet fuel appeared elusive, until recently.

The second main way that aviation affects the climate system is through the creation of contrails. Contrails occur when moisture in jet exhaust condenses in the high altitude cold ambient environment to create lines of thin cirrus clouds, comprising ice crystals, whose net effect is to warm the Earth further. While innovation in flight path planning is ongoing in an effort to reduce contrail formation, off the shelf solutions to replace jet fuel appeared elusive, until recently.

On August 6 and 7, 2022 I attended the Abbotsford Air Show to learn about innovation in the aviation industry and the use of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), sometimes known as biojet fuel. I was quite excited by what I discovered as it appears that Canada is uniquely positioned to be an international leader in this area.

It was evident to me that the aviation industry is deeply concerned about their greenhouse gas emissions and that they are investing heavily in carbon-neutral technology pathways. While we can expect to see the increasing use of electric engines, hydrogen fuel cell technology and even potentially hydrogen combustion from onboard cryogenic storage tanks, these will likely only be available for commuter, regional and short haul flights (<120 minute with < 150 passengers) over the next decade or two. Unfortunately, such short-haul flights only account for about 27% of global carbon dioxide emissions from the aviation sector whereas medium and long haul flights account for the remaining 73%. And so, if we want to reduce emissions from the aviation sector over the next few decades, widespread adoption of SAF made from renewable organic waste will be required.

A number of companies, including Neste, Lanzajet and World Energy have either been recently established or are already heavily invested in producing SAF using renewable ethanol from waste (such as cooking oil) as an initial focus. Of course, establishing sustainable supply chains for organic waste that don’t involve food stocks (e.g. Canola) or limited supplies of cooking oil will be needed if SAF is to scale up globally. Other companies (e.g., Licella, Ensyn, Steeper Energy etc.) are also heavily invested in exploring the potential of non-food source related waste (e.g. from forestry, municipal waste, sewage, waste plastic etc.) as feed stock for renewable fuels.

And herein comes the potential opportunity for British Columbia and Canada.

And herein comes the potential opportunity for British Columbia and Canada.

First, the University of British Columbia’s Department of Wood Science is already considered an international leader in biofuel research and hosts the British Columbia Sustainable Marine, Aviation, Rail and Trucking (BC-SMART) consortium. British Columbia and Canada are well positioned to capitalize on investments in research and innovation in this sector.

Second, British Columbia has no shortage of wood or other organic waste that could potentially sustain domestic supply chains for biofuel production.

Third, wood waste, such as slash piles left behind after logging activities have concluded, are often either burnt in situ, left to decompose, or eventually act as a fuel source for wild fires. Removing this waste and converting it to biofuel has significant environmental co-benefits.

Fourth, wood waste is distributed throughout British Columbia, and in particular rural BC. Capitalizing on the opportunities afforded by the harvesting of wood (or other organic) waste would provide distributed economic opportunities for indigenous and non-indigenous communities across our province.

In 2018 I wrote extensively about the challenges and opportunities associated with greenhouse gas reductions in British Columbia. In particular, I noted that embedded in the confidence and supply agreement that I signed with the BC NDP in 2017 was the following commitments:

Climate Action

-

- Implement an increase of the carbon tax by $5 per tonne per year, beginning April 1, 2018 and expand the tax to fugitive emissions and to slash-pile burning;

- Deliver rebate cheques to ensure a majority of British Columbians are better off financially than under the current carbon tax formula;

- Implement a climate action strategy to meet our targets.

While British Columbia is on track to dramatically reduce its greenhouse gas emissions in the years ahead associated with our Clean BC climate plan, one of the policy commitments we didn’t deliver on was an expansion of the carbon pricing to slash pile burning. This is important since if a price is attached to slash emissions, an incentive is created to avoid this potential liability and so forestry (and other) companies would be given an economic reason to extract slash from forest operations. Such a price could be set directly (on emissions) or indirectly (via regulation) as was done for fugitive emissions in the oil and gas sector.

So in summary, it strikes me that the sustainable fuel sector for long haul transportation represents an incredible opportunity for innovation that British Columbia and Canada can capitalize on. The economic, environmental and social benefits of investments in this area appear to be far-reaching.

Coming back to the Abbotsford Air Show, one of the planes that I toured was the Boeing P-8A (pictured above). The P-8A is a military plane designed for long-range reconnaissance, surveillance, and submarine detection missions. And here is why this is important.

Canada is in the final stages of a procurement process:

Canada is in the final stages of a procurement process:

“To equip the Canadian Armed Forces with a long-range manned Command, Control, Communications and Computers (C4) and Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) and Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) aircraft with extended capabilities to replace the CP-140 Aurora.”

The Boeing P-8A represents a solution that may meet the needs of this procurement. Why this is interesting is that the P-8A is already capable of operating on 50% SAF and Boeing has committed to meet a 100% SAF capability by 2030.

Touring the P-8A felt like I was exploring a repurposed Boeing 737 for good reason! The P-8A has a Boeing 737-800 body, 737-900 wings, a 737 cockpit and a 737 engine with a substantive increase in available electrical power. Fully 86% of the commercial components within the P-8A are common with Boeing’s 737 series, the world’s most prevalent passenger jetliner.

Figure: Four images taken inside the Boeing P-8A illustrating its galley and washroom similarities with the Boeing 737 passenger jetliner.

While I do not have the expertise to assess the military capabilities of the P-8A, I learned that 156 of them with over 450,000 logged flight hours, are in military use worldwide (in the US, India, UK, Norway, Germany, Australia, New Zealand and South Korea).

Figure: Four images taken inside the Boeing P-8A showing its military workstations and the sonobuoy storage/release systems

Figure: Two images of the underside of the Boeing P-8A wing indicating wing pylons that allow for the attachment of up to 3,000 lb weapons.

What excited me most about my tour of the Boeing P-8A at the Abbotsford Airshow is that I came away with a sense of optimism and hope for the future of the aviation industry. Imagine the potential for the Canadian military to show international leadership by investing in a sustainable replacement for its CP-140 Aurora fleet that would create a local market for sustainable air fuels produced from locally-sourced slash and other organic waste. While scaling up the use of SAF in the global aviation industry remains a challenge, Canada can do its part positioning itself as a early adopter and international leader in the area.

Moving on from Provincial Politics: A Climate for Hope

To bring closure to my 7 1/2 years as an MLA for Oak Bay-Gordon Head and 5 years as leader of the BC Green Party I felt it was important to add this video to my archived MLA website. Moving forward, I plan to continue my work on climate solutions on the local, provincial, national and international level.

This YouTube video was produced by Robert Alstead, the same person who created the documentary “Running on Climate”. That documentary provided an inside look into the 2013 election campaign set within a greater climate change narrative.

This YouTube video might be of interest to some as it gives insight as to why I got into and out of politics. The book that I refer to in this video has the working title: “A Climate for Hope” and not “A Vehicle for Change”.

Tribute to a Canadian Hero: John Hillman

Today in the legislature I rose to pay tribute to a constituent, John Hillman, who, at the age of 101, recently completed his goal of walking 101 laps around the courtyard of his residence at the Carlton House in Oak Bay to raise funds for Save the Children Canada’s Emergency COVID Relief Fund.

Today in the legislature I rose to pay tribute to a constituent, John Hillman, who, at the age of 101, recently completed his goal of walking 101 laps around the courtyard of his residence at the Carlton House in Oak Bay to raise funds for Save the Children Canada’s Emergency COVID Relief Fund.

Below I reproduce the text and video of my two minute tribute.

Below I reproduce the text and video of my two minute tribute.

As an update, during the afternoon of July 29 I was able to visit John Hillman at Carlton House and present him with a number of presentation copies of the statement.

Video of Tribute

Text of Tribute

It gives me great honour to rise today to pay tribute to a remarkable constituent — Mr. John Hillman.

At the age of 101, Mr. Hillman set a goal of raising $101,000 for Save the Children Canada’s Emergency COVID Relief Fund by completing 101 laps around the courtyard of his residence at the Carlton House in Oak Bay.

He was inspired by 100-year-old war veteran Tom Moore who raised over 55 million dollars for the UK’s National Health Service, by walking around his garden 100 times with a walker.

Mr. Hillman not only completed the 101 laps (plus a victory lap), but he easily surpassed his expectations by raising $166,551.

Mr. Hillman was born in Newport, Wales in 1919. Like all young Welsh men at the time, he was an avid rugby player. In fact, Mr. Hillman’s father Jack represented Wales on their national team. John, on the other hand, went on to compete for Wales in fencing.

At the age 17, and with little prospect for local employment Mr. Hillman left Wales to join the Royal Air Force.

In 1939, he and his squadron were posted to France where Mr. Hillman served as a wireless operator.

As allied forces fled to Dunkirk ahead of the rapidly advancing Wehrmacht, John Hillman, and the other 59 members of his squadron were cut off and left behind.

As allied forces fled to Dunkirk ahead of the rapidly advancing Wehrmacht, John Hillman, and the other 59 members of his squadron were cut off and left behind.

They were told this:

“you lads stay behind, clean up, and make your way back as best you can”.

Their goal was to head south to board the English troop carrier, the HMT Lancastria.

Blessed with a stroke of good luck, Mr. Hillman arrived in the French port of Saint-Nazaire a day late so missed his opportunity to board the ship.

Tragically on June 17, 1940, just offshore from the port, the Lancastria was bombed and sank in just 20 minutes. Some 4000 men, women and children died in what remains the greatest loss of life in British maritime history.

Mr. Hillman subsequently made his way northwards to Brest, where he was able to escape to England on a Royal Navy destroyer.

Mr. Hillman subsequently made his way northwards to Brest, where he was able to escape to England on a Royal Navy destroyer.

It was in England that Mr. Hillman met and married his wife Irene. The couple have been married for 78 years, and when their daughter also married a Canadian, Mr. and Mrs. Hillman started to visit Canada.

Mr. Hillman eventually retired in Ottawa in 1988 from his career as an electrical engineer. After a brief return to the UK, Mr. and Mrs. Hillman moved back to Canada and settled in a house on Beach Drive in Oak Bay.

When asked why he undertook the fundraiser, John Hillman said “I owed Canada something”.

A truly humble man, Mr. Hillman has a wonderful sense of humour and brings joy to all who know him.

As a lovely tribute to support Mr. Hillman, his 9-year-old great-grandson did a parallel walk in Kingston, Ontario.

What did Mr. Hillman do when he attained his goal of 101 laps? “I had a cold beer” he commented. Now that was truly well deserved!

Please join me in celebrating the remarkable accomplishments of a Mr. John Hillman. Thank you.