Uncategorized

A Bill to Reduce Preferential Treatment of Non-Resident Hunters

Today in the legislature I tabled a private members bill entitled: Wildlife Amendment Act (No. 2), 2015. The purpose of this Bill was to reduce the preferential treatment of non-resident hunters.

Today in the legislature I tabled a private members bill entitled: Wildlife Amendment Act (No. 2), 2015. The purpose of this Bill was to reduce the preferential treatment of non-resident hunters.

Limited entry hunting (LEH) is a lottery based management system used to organize the harvest of species in situations where there are too few animals and too many hunters. Currently the Wildlife Branch has different rules for resident and foreign hunters when it comes to obtaining LEH permits: Residents must enter a lottery draw, but foreigners (who are required to hire guide) can simply buy their way in. By eliminating the minister’s discretion to make separate rules for each group, this bill requires ALL hunters to enter a lottery for their LEH tags, as is done in other jurisdictions.

As it currently stands, residents may enter a lottery year after year and still not get drawn, while a non-resident can buy his or her way in every year if they want. This bill seeks to ensure certain groups do not have unfair access to LEH permits.

While people may wonder why we need a lottery system for non-residents when they are already restricted by the allocation split, it is worth noting that the split between permits allocated for resident and non-resident hunters is as high as 60% – 40% for some species. By comparison, Alberta sets non-resident allocations between 2-7 percent with a maximum of 10 percent and Washington State has limited non-resident wildlife allocations to approximately 5 percent. Non-resident hunters in B.C. are already getting a bigger share here than anywhere else in North America – and they are pay significantly less too. A non-resident hunter coming to B.C., for example, can buy a moose tag directly for $250.00 Canadian. In Washington State they would have to enter a draw and if their application got randomly selected they would have to pay $1,652.00 USD.

The price and availability of hunting permits is, of course, influenced by animal abundance and hunter demand. In B.C. compared to other jurisdictions in North America, however, they also seem to favour guide outfitters and their non-resident clientele over resident hunters. I tabled this bill today to reduce some of that unfair legislation.

Below I provide a video of my introduction along with its transcript. At the end i also include a copy of the proposed bill

Video of Bill Introduction

Text of Bill Introduction

A. Weaver: It’s my pleasure to introduce this bill — which, if enacted, would remove the minister’s ability to designate and exempt classes of applicants from having to enter lotteries or other methods of random selection when seeking limited-entry hunt permits. If enacted, these amendments would require all hunters to enter draws for their limited-entry hunt permits, regardless of resident, non-resident or non-resident alien designation, as is done in other jurisdictions.

As it currently stands, local hunters have to enter a lottery if they want to harvest an animal managed under the limited-entry hunt system, but out-of-province hunters can simply buy a permit for the same species and management unit area. Foreign hunters coming to B.C. already enjoy cheaper permits and greater allocation percentages than nearly every other jurisdiction in North America. It’s clearly unfair that they can buy their way into limited-entry hunts year after year, when British Columbians are left entering lotteries in the hopes of being granted the opportunity to harvest a public good in their home province.

The limited-entry hunt system is an important management and conservation tool. Its designation through the lottery system should be implemented across the board, mirroring other jurisdictions that require non-resident hunters to enter limited-entry hunt lotteries. Like every state in America, this legislation envisions a separate draw for local and out-of-province allocations.

I look forward to second reading of this bill. I move that this bill be placed on the orders of the day for second reading at the next sitting of the House.

Text of Bill M230

Wildlife Amendment Act (No. 2), 2015,

THE WILDLIFE ACT [RSBC 1996] Chapter 488. The Act is amended by:

Section 16 of the Act is amended by striking out sections 16 (1) (b.1) and 16 (3)

Limited entry hunting authorization

16 (1) The minister, by regulation, may

(a) limit hunting for a species of wildlife in an area of British Columbia,

(b) provide for limited entry hunting authorizations to be issued by means of a lottery or other method of random selection among applicants,

(b.1) provide for exceptions that the minister considers appropriate to the random selection among applicants in conducting a lottery or other method of random selection among applicants under paragraph (b), and

(c) do other things necessary for the purposes of this section.

(2) An application fee collected under a lottery or other method referred to in subsection (1) must be paid into the general fund of the consolidated revenue fund.

(3) In making regulations under subsection (1), the minister may define classes of applicants and make different regulations for different classes of applicants.

Appreciation for Oak Bay Emergency Services

This evening I had the distinct honour of attending the Oak Bay Emergency Services Appreciation Banquet. I had the opportunity to extend deep appreciation and respect for the daily efforts and dedication of Oak Bay’s emergency services towards the health, safety and betterment of our community.

Text of my remarks

Good evening and thank you for the kind invitation for Helen and me to attend tonight’s banquet. We are honoured to be here with you.

Please let me join others here in thanking you, Oak Bay’s emergency service members, for your dedicated, professional and selfless service to our community — for being there in our times of need.

I am pleased to be here tonight to honour the work you do in the service of others. As citizens, we are reassured in knowing that you are there and ready to help us when needed. Dave Carroll’s song in the video (also shown below) we just watched says it all — you are everyday heroes. To quote from the lyrics:

When people in the world need savin’

The saviours who answer the call

Don’t get paid anymore for danger

Or get to pick the one’s they want

They just go to where the few will go

To maybe lay it all on the line

Just to do their job, do it one more time

Many of us may only have brief contact with you in the course of our lives, but the work you do has life-long impact on so many that you serve in the community.

You encounter and witness events in the course of your work that most of us will never see. I’m sure you sometimes wish some things could be unseen, but that is not your reality. There is often a heavy price to pay for your work – with shift work, emergency call-outs, interrupted family life and the inherent danger you face in the course of your duties. You are often dealing with emotionally difficult and highly intense situations. Instead of running from danger, you run courageously towards it and focus on the job you are trained to do.

To quote from Franklin D. Roosevelt: “Courage is not the absence of fear, but rather the assessment that something else is more important than fear”.

We are also very appreciative for all the work that you do to support our community. We see you at numerous community events, you fundraise for charity and undertake important liaison work in the schools and through education in the areas of prevention and safety.

Helen and I would like to extend our deep appreciation and respect for your daily efforts and dedication towards the health, safety and betterment of our community.

Dave Carroll’s Everyday Heroes Video

Saving Woodland Caribou from extirpation will also save old growth forests

Over the last few months British Columbia’s controversial wolf cull has been the subject of substantial public dialogue. Like most MLAs, I receive ongoing communication from numerous British Columbians questioning the rationale behind the government’s approach. One of the most recent communications I received was from a young woman named Katie. She started off her email saying:

“My name is Katie, and I oppose the wolf cull. In school we learned about predator prey relationships. I know you probably won’t care, and that the government will go ahead with it anyway, but please read this…”

I found her email to be a source of inspiration. Despite her apparent cynicism towards politicians, she took the trouble to express her concerns to me (even though she is not a constituent). Her email struck a chord. I campaigned on a promise of evidence-based decision-making and giving youth in our society, the generation that will have to live the consequences of the decisions my generation is making, a voice in the legislature.

The BC NDP have not contributed anything of significance to this issue. Instead, when questioned they offer up a sense of vague disappointment and an endorsement of “long term habitat protection.” Habitat protection is vital of course, especially for herds that are still relatively healthy, but if that is the only policy we offer the threatened mountain caribou they will all be dead by the time the trees grow back.

The policies that the B.C. Liberals are putting forward are concerningly intertwined with the interests of industry and lack safeguards that would ensure other herds do not follow the South Selkirk and South Peace mountain caribou to the brink of extirpation.

As a member of the legislature it is my job to do more than outright oppose policies I don’t like. I need to be able to substantially contribute to the debate and provide feasible solutions and alternatives. So, I got my office to research the topic, and threatened species management more generally, in great detail. Our subsequent analysis derived from a literature review and many hours of discussions with scientists, including wildlife biologists who have expertise in the area.

When you start rationalizing culling one species to protect another you also introduce an ethical element that needs to be considered alongside the science. Is it ever justifiable to kill one animal in the name of saving another? Science can never answer that question.

Let one of those species become threatened and your situation becomes immensely worse. Ethically, the wolf cull is a horrible response to an ecosystem out of balance. From a management perspective, we need to focus on endangered mountain caribou and the logging practices that got them to where they are today.

Before humans began changing the North American landscape, woodland caribou’s range extended largely across Canada. While northern subpopulations of caribou once roamed in massive herds numbering in the thousands, mountain caribou have always been more sparsely distributed. Mountain caribou survive on a lichen-rich diet, especially in winter months, a food source that is intricately linked to old growth forests. As industrial development and logging activities began to fragment their old growth forest ecosystems, mountain caribou populations began to destabilize. Not only has logging demolished much of their habitat directly, the associated road networks and areas of new growth forest have also brought an influx of moose and white-tailed deer into the ecosystem. Populations of wolves then followed the moose and deer (their primary prey) and caribou (their secondary prey) are now being killed as bycatch. We are scrambling to save herds of mountain caribou on the brink of extirpation because we weakened their natural habitat and made them vulnerable to increased predation. Of this, there is no disagreement within the scientific community.

The future for these threatened caribou is not looking promising; climate change is altering food supplies and habitat conditions, industrial activities are unbalancing ecosystem composition, and human settlement is concentrating the necessity of protected wilderness.

As per requirements enforced under Canada’s Species at Risk Act, the province has protected 2.2 million hectares of forest from logging and road building where populations of caribou are classified as threatened. These areas have immeasurable value for preserving British Columbia’s biodiversity, especially in light of ongoing global warming. But these areas, a substantial fraction of which are old growth, also have substantial commercial value.

Recent Freedom of Infomation documents reveal that the B.C. Liberals met with forest industry representatives when developing plans to save endangered caribou. The Minister of Environment said it is common practice to consult all stakeholders, but I worry that industrial pressures are playing too big a role in habitat allocation. My concern, that I raised last week during Question Period in the British Columbia Legislature, is that vast tracts of forests will stop being preserved the moment the threatened caribou herds go extinct. With their death, the protection of their habitat will no longer be enforceable under the Species at Risk Act.

We need to protect as much land as possible from all human activities so remaining wildlife populations have the space and resources needed to respond to predation and food supply challenges. The cost of restricting industrial development in B.C.’s forests would be expensive in terms of lost revenue, but it would save us having to micromanage every dwindling species.

Where is our provincial government on species protection? Shockingly, we are one of only two provinces (the other being Alberta) that don’t even have any endangered species legislation. Protecting more habitat for our biological diverse ecosystems should be the goal, and creating a provincial endangered species act would be a good place to start.

At the same time, it’s crucial that critical environmental issues are not framed simplistically. There are very real consequences to allowing caribou herds to become extirpated. And one of the most profound of these will be the subsequent logging of remaining stands of British Columbia’s old growth timber.

Electoral Boundaries Commission Report – Changes to OBGH

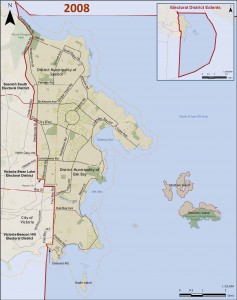

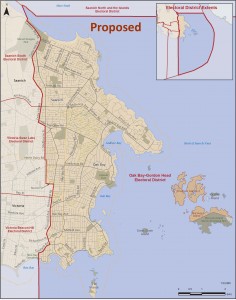

Today in the Legislature we continued debate on a motion to support the changes to electoral boundaries proposed by the British Columbia Electoral Boundaries Commission. The final report, dated September 24, 2015, recommends the addition of two new ridings (one in Richmond and one in Surrey) and sees changes to 48 of the current 85 electoral districts. The riding of Oak Bay – Gordon Head is slightly modified.

As shown in the two maps below, the boundary between Victoria-Beacon Hill and Oak Bay-Gordon Head shifts from Foul Bay Road to Richmond Avenue all the way from Haultain Street to Fairfield Road near the water. This brings the Royal Jubilee Hospital, the Victoria College of Art, Glenlyon-Norfolk Pemberton Woods campus and Margaret Jenkins Elementary (my alma mater) into the riding. The riding boundary then follows Fairfield Road until St. Charles Street where it turns, beside Ross Bay cemetery, until it reaches Dallas Road.

As noted in their Mission Statement:

In a rare moment of unanimity, every MLA in the legislature spoke, or is continuing to speak, in favour of the motion. I did as well today, and reproduce part of the video and text below.

2008 Proposed

Video of My Comments

Text of My Comments

A. Weaver: It gives me great pleasure to rise and speak to the motion before, the motion which is:

“Be it resolved that in accordance with section 14 of the Electoral Boundaries Commission Act, R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 107, the proposals contained in the Final Report of the Electoral Boundaries Commission tabled in the Legislative Assembly on September 28, 2015 be approved.“

Now, to remind those riveted to their television sets across British Columbia, section 14 of the Electoral Boundaries Commissions Act states the following:

“If the Legislative Assembly, by resolution, approves or approves with alterations the proposals of the commission, the government must, at the same session, introduce a Bill to establish new electoral districts in accordance with the resolution.“

I rise, along with every other member in this House, to speak in support of the resolution before us and, specifically, to thank, at the onset, the work done by the Electoral Boundaries Commission and, in particular, the Hon. Mr. Justice Thomas J. Melnick, the commission chair; Beverley Busson, the commissioner; and Keith Archer, Chief Electoral Officer and commissioner.

Now, this report was done, obviously, in an non-partisan manner. It is one that reflected the values of British Columbians in terms of trying best to put their needs and interests first and foremost in the setting of electoral boundary limits

I represent the riding of Oak Bay–Gordon Head, a riding that, under these proposed changes, would expand ever so slightly to an area of 330 square kilometres with a 4.8 percent deviation above the provincial average in terms of population, and the population would be 55,689.

Oak Bay–Gordon Head is 330 square kilometres because it contains quite a number of islands off the shore, and I must confess to being remiss to visiting these islands frequently. Trial Island, the Chatham Islands, Discovery Island, Griffin Island, Great Chain Island…. There’s a number of these islands which are within the electoral boundary, and they carry over from before. Very sparsely populated. Trial Island has a lighthouse keeper. Chatham Islands — a First Nations reserve — the last long-time resident recently moved off that. And Discovery Island is largely a marine park. Nevertheless, I do represent these ridings as well as the entire district of Oak Bay contained within the boundary and a substantial component of Saanich.

Now, in the capital region, the proposed changes for my riding are subtle. They’re subtle, and they come at the expense with respect to my colleague in Victoria–Beacon Hill. The Electoral Boundaries Commission, in reflecting upon the boundary changes, really had one of two changes that it could make consistently in order to actually bring our population number up, which I recognize has gone down a little bit.

One was near Mount Doug, where, along Cedar Hill Road, there’s a small subdivision towards the north side that could have been brought in. Historically, this was part of the riding when the Hon. Ida Chong was the MLA representing the region, but in previous reports it got taken out. And the other, which, frankly, I think, is more supported, is to continue the natural divide between Victoria–Beacon Hill and Oak Bay–Gordon Head along Richmond Road.

The reason why I say it’s a natural divide is because there was this very odd little corner by Jubilee Hospital that, frankly, confused the voters, because this little corner in Oak Bay–Gordon Head was shared by the member for Victoria–Swan Lake, the member for Victoria–Beacon Hill and my riding. In fact, it was not uncommon for constituents in Oak Bay–Gordon Head to get electoral information from constituents in Victoria–Beacon Hill and vice versa, because it was this little odd corner in the riding that has been corrected in this.

Oak Bay–Gordon Head is very proud to bring the Royal Jubilee Hospital back into our riding. It’s a natural home for the riding because so many constituents live nearby it and work nearby it. We get to continue down Richmond Road. We now bring the Victoria College of Art — another natural home for Oak Bay–Gordon Head, the Victoria College of Art — and another high school, making us, in Oak Bay–Gordon Head, I would reckon, probably the most high-school-rich, university-rich, college-rich riding in the province.

With the inclusion now of the senior school of Glenlyon Norfolk, we now have, in Oak Bay–Gordon Head, three public high schools: the brand-new Oak Bay, Lambrick Park — the school my daughter graduated at — Mount Doug, St. Michael’s University School and now Glenlyon as well. Five high schools. But on top of that, we also have Camosun College, which is right on the boundary there of Richmond Road, and the University of Victoria. And we have a diversity of other colleges, including the Victoria College of Art and the Canadian Centre for the Performing Arts. We have a number of elementary schools, some of them private, some of them not.

We have Maria Montessori, an additional high school that actually, this year, is graduating its first grade 12 class. It used to just be K to 7, but now it is…. So that would make us three private schools, three public schools, a college and a university, and we’re very proud to bring the hospital into our riding as well.

Endangered Species Management: Caribou versus Wolves

Over the last few months British Columbia’s controversial wolf cull has been the subject of substantial public dialogue. Like most MLAs, I receive ongoing communication from numerous British Columbians questioning the rationale behind the government’s approach. These communications crescendoed when well known singer Miley Cyrus spoke out against the cull and urged her more than 23 million followers to sign a petition. One of the recent communications I received was from a young woman named Katie. She started off her email saying:

“My name is Katie, and I oppose the wolf cull. In school we learned about predator prey relationships. I know you probably won’t care, and that the government will go ahead with it anyway, but please read this…”

I found her email to be a source of inspiration. Despite her apparent cynicism towards politicians she took the trouble to express her concerns to me (even though she is not a constituent). Her email struck a chord. I campaigned on a promise of evidence-based decision-making and giving youth in our society, the generation that will have to live the consequences of the decisions my generation is making, a voice in the legislature. And so Claire Hume and I decided to look at BC’s controversial wolf cull a little more closely. What follows is an extensive analysis of the available literature. Our analysis derived from many hours of discussions with scientists, including wildlife biologists, with expertise in the area. I look forward to your comments.

Is it justifiable to kill one animal in the name of saving another? What if one of those animals is endangered?

Is it justifiable to kill one animal in the name of saving another? What if one of those animals is endangered?

I have always maintained that humans have a moral obligation to prevent endangered species from going extinct, but wildlife management conflicts in which species are pitted against one another are always challenging. For a variety of industrial, social, or budgeting excuses, they are often situations that have been allowed to escalate far past a point of simpler intervention. When you start rationalizing culling one species to protect another you also introduce an ethical element that needs to be considered alongside scientific findings. Let one – or both – of those species become threatened or endangered and your situation becomes immensely worse.

Many ecosystems have been altered so drastically that we can no longer let nature take its course. If we don’t continue to intervene with the mountain caribou crisis we are currently facing in B.C., for example, it will not be long before the remaining herds in the South Selkirk and Peace regions are extirpated. Ideally, our wildlife management system would never let things get this bad. But it happens. And when it does we have no choice but to make tough decisions.

In January I wrote to the Minister of Forests, Lands, and Natural Resource Operations to ask a number of questions regarding the rationale for the wolf cull in the South Selkirk Mountains and the South Peace region. In response Minister Thompson sent me the supporting data that backed up their wolf cull. I read through it and agreed that with 18 caribou left we needed to take immediate and drastic action to ensure as many caribou as possible survived through another breeding season. Since then, the issue has continued to polarize our province with both sides of the debate claiming science. And in many ways, both sides are right. There is supporting evidence that suggests, for certain situations, that culling wolves is an appropriate wildlife management tool. There are also many other studies that conclude that it is an ineffective solution, one that could make the situation even worse while causing a great deal of animal suffering in the process.

So, where do we go from here? We do a literature review of the available relevant research and we have a conversation. We explore the feasibility of other options and try to find a solution that maximizes protection for threatened species while minimizing the harm done to all other animals. Over the last few months my office has been talking to scientists and analyzing data across disciplines, across species, and across the country (across continents in one case) to learn more about endangered species management.

Lessons from the Vancouver Island Marmot

In the late 1990s the Vancouver Island marmot population dropped to 70 members. While clear-cut logging in marmot territory was thought to be the initial and main reason their population numbers were plummeting, the landscape changes also led to increased predation. Between 1995 and 2005 predation by wolves, cougars, and eagles accounted for 80% of marmot mortality. Much like the caribou, habitat destruction was the main catalyst for their decline and wolves moved in to take advantage of the new open landscape. I reviewed the group’s marmot recovery plan and contacted them to ask why predator control has never been a part of their strategy.

Their Executive Director, Viki Jackson, said they tried everything they could think of on Mount Washington in place of culling predators: they collared cougars and brought dogs in to scare them away, had “shepherds” stay with the marmot colonies, put dirty human clothes around to deter predators, put up fences, and used bear bangers. Having people camp with the marmots 24/7 worked well, Jackson said, but the other attempts didn’t do much. At the same time, they started to have success with their captive breeding program. Without their active intervention the Vancouver Island marmot would have likely gone extinct years ago.

When it comes to endangered species management, Jackson said, there will never be consensus but you have to do everything in your power to protect key females when animal numbers drop to extreme lows. You need to get them over the extinction hump and stable enough that other conservation efforts have a chance to help.

While the specifics of this case do not exactly translate to the needs of larger, transient animals like caribou, I found their imaginative approach to crisis species management inspiring. Threatened species in our province are facing very modern difficulties as they try adapt to new stressors and habitats changed by development. Perhaps we should be trying to combat these challenges with equally modern and innovative solutions before defaulting to predator culling, a practice that only targets one aspect of highly complex situations. With this thought I contacted Dr. Adam Ford from the University of Guelph’s Department of Integrative Biology to talk about the use of technology in wildlife research and management.

GPS Management

Global Positioning Systems (GPS) placed on collars, Dr. Adam Ford explained, can be used to pinpoint, with high accuracy, the location of an animal at a given time. It is also possible to track animals and process data almost instantaneously. Knopff and his colleagues, for example, used GPS to track cougar predation to study predator/prey interactions with immediate data retrieval. “Real time monitoring has enormous potential in the fields of wildlife ecology and conservation, especially for at-risk wildlife,” their report states.

With these systems you can monitor the spatial relationship between an animal and a wide variety of geographical features. Data can be collected that orients an animal in relation to specific points (like feeding grounds), linear features (roads, fence lines, fishing nets, etc.) and spatially dynamic features (like a mobile herd of livestock). Given these tracking advancements, and the incredible success scientist and conservation officers have had using them in wildlife management settings, it is hard not to feel hopeful imagining the great potential for their use with woodland caribou in BC. I think it would be worth assessing, for example, the feasibility of attaching GPS’ to select members of threatened caribou herds and their neighbouring wolf packs, as suggested by Dr. Ford. You could outfit caribou and wolves with GPS collars, Dr. Ford explained, and program them with a GSM-linked messaging system that warns managers when wolves, say, are within 1 km of the caribou. The managers could then travel to the coordinates shown in the GSM message, and herd the wolves away with aversive conditioning. That way, intervention is case-specific and the helicopter time is used much more efficiently. They use this method in Kenya with elephants to keep them away from crop fields and refer to it as ‘geofencing‘.

I appreciate comparing elephants to caribou sounds dangerously like an apples-to-oranges tangent, but the success the Save the Elephants organization has had with GPS-based wildlife management is incredible and certainly worth further consideration. Their Geo-fencing program started ten years ago, in the hopes of reducing human-elephant conflicts. “Kimani was the first elephant to be collared and tested under the Geofencing [system]. He became the focus of the Ol Pejeta management due to his considerable skill in breaking expensive fences. In December 2005 he went on a crop-raiding spree that lasted 21 straight nights.”

In phase one of the project they programmed a virtual fence line (or string of coordinates) into the GPS collar worn by the elephant. If the elephant strays out of his designated range – suggesting he is heading towards farms or villages – his collar sends a text message with his exact location to the reserve managers, who can then mobilize and intervene with negative reinforcements before he does too much damage. After only a few months in his GPS collar, Kimani the elephant had stopped breaking fences. Years later, Kimani has still not returned to his crop-stomping ways.

Another breakthrough, which does not relate to caribou but highlights the brilliant potential for innovative wildlife management strategies, was their elephants and bees hypothesis. “Having found that elephants run from the sound of bees, in 2007, we set up a unique beehive fence line in the area to see if they would deter elephants from raiding crops. To test our hypotheses, we geo-fenced several known crop-raiding elephants to see if their behaviour changed once confronted with large concentration of bees. Thanks to the geo-fencing technology, we were able to witness and confirm that bees did in fact deter elephants from crop raiding.”

Elephant-caribou differences aside, the technology is transferable. “The real-time monitoring algorithms presented here for monitoring African elephants (proximity, geo-fencing, movement rate, and immobility) are widely adaptable and applicable to monitor a variety of behaviours across numerous species,” wrote Wall et al.

While there is considerable consensus within the scientific community about the effective use of technology in wildlife management, I have found concerning disagreement about the role of wolves in caribou declines and the impact of culling them. What follows is a literature review of sorts, of the relevant research that has been done on this subject.

Wolf Cull Literature Review

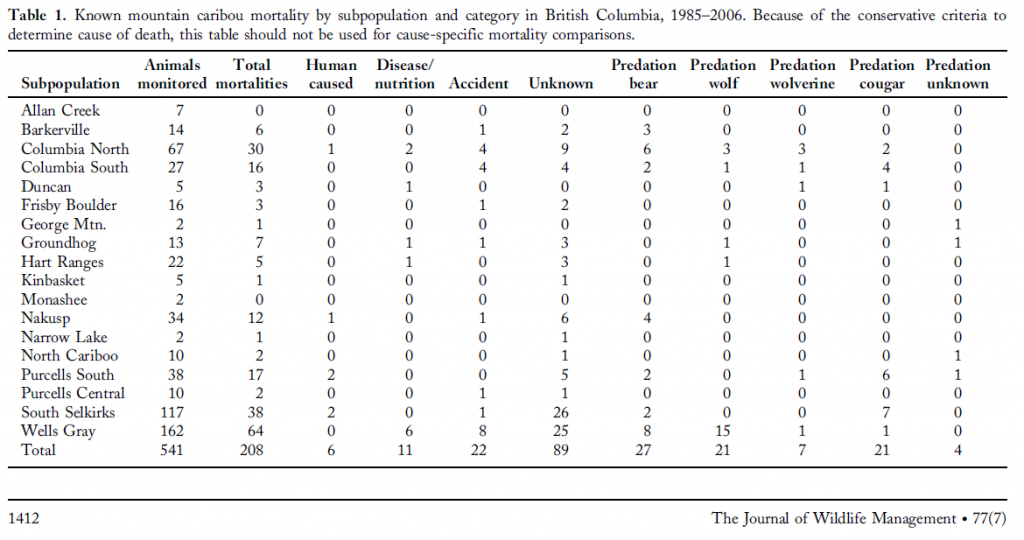

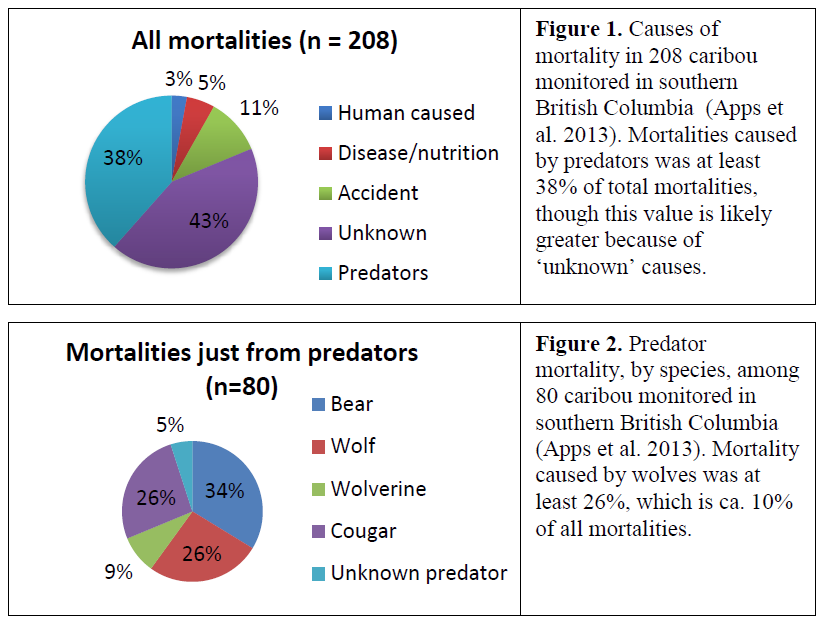

Apps et al. studied the GPS, very high frequency (VHF), and motion sensor data collected from 541 caribou over 22 years. When the collared animals stopped moving for prolonged periods researchers tracked their location and tried to determine the caribou’s cause of death. In their cause-specific mortality analysis of mountain caribou in B.C. they found that wolves are only one of many important sources of mortality for caribou. The data, though limited, indicates that wolves are not necessarily the primary killer of mountain caribou. In fact, it is possible that bears and cougars may have a stronger impact on caribou numbers. That said, I spoke to Dr. Clayton Apps about his study and he cautioned that the data should not generalized too broadly as it pertains to specific sampling cases. The wider conclusion of his work focused on caribou vulnerability as it relates to landscape changes. Wolf predation was found to be concentrated at lower elevations and areas with a higher concentration of roads, which they used as a navigational advantage when hunting.

On a similar theme, DeCesare’s data links industrial development with increased encounters between wolves and caribou, which in turn can lead to increased predation. Supporting that notion, other studies have illustrated the considerable impact wolves can have on local ungulate populations. Kortello et al. conducted a study that analyzed the diet and spatial overlap between wolves and cougars in Banff National Park. During their research they observed a 65% decline in local elk populations following the arrival of wolves. This shift caused cougars to switch from a primarily elk winter diet to one that favoured deer and other alternative prey options.

At this point we have a fairly clear picture of a wolf – caribou relationship that has been knocked out of whack in areas that have been altered by industrial development. Wolves eat caribou, even more so when roads and cleared forests give wolves efficient access to a larger range while simultaneously limiting caribou’s own food sources. If we have too few caribou, and too many wolves, it is easy to conclude a wolf cull would be an appropriate response. Some short term studies support that assumption. Bergerud et al. for example suggested that a wolf cull in Northern B.C. and the Yukon lead to increases in ungulate populations, but many studies do not.

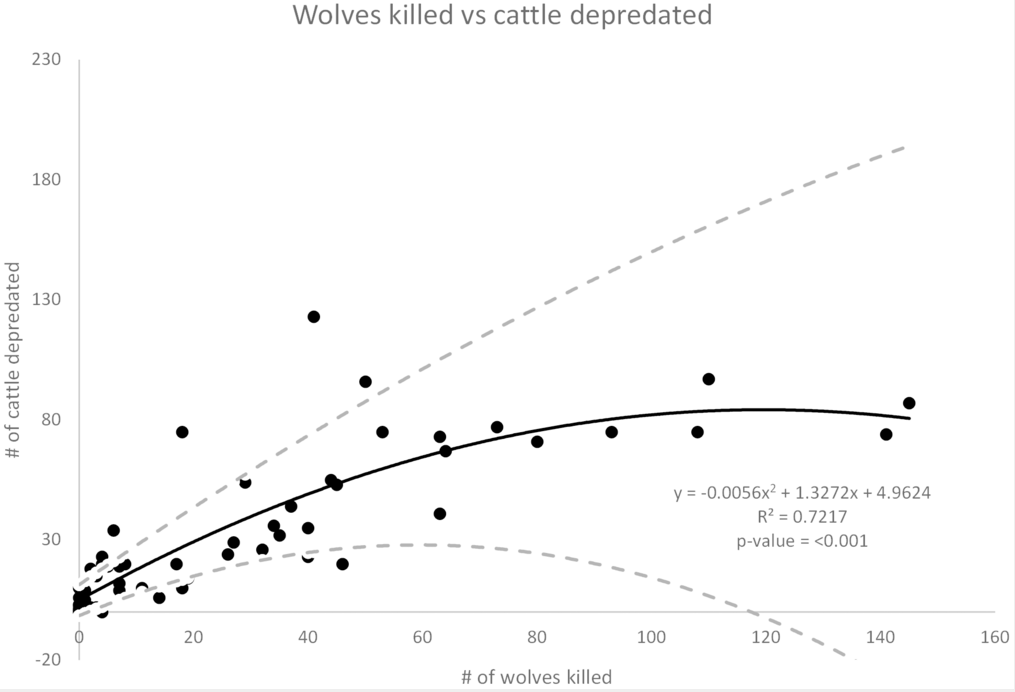

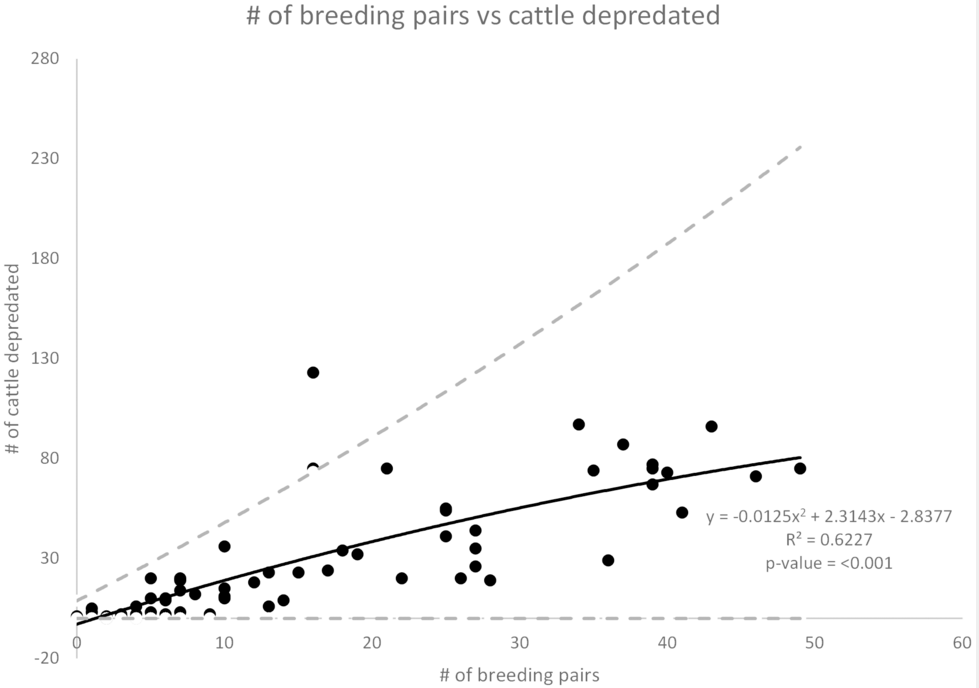

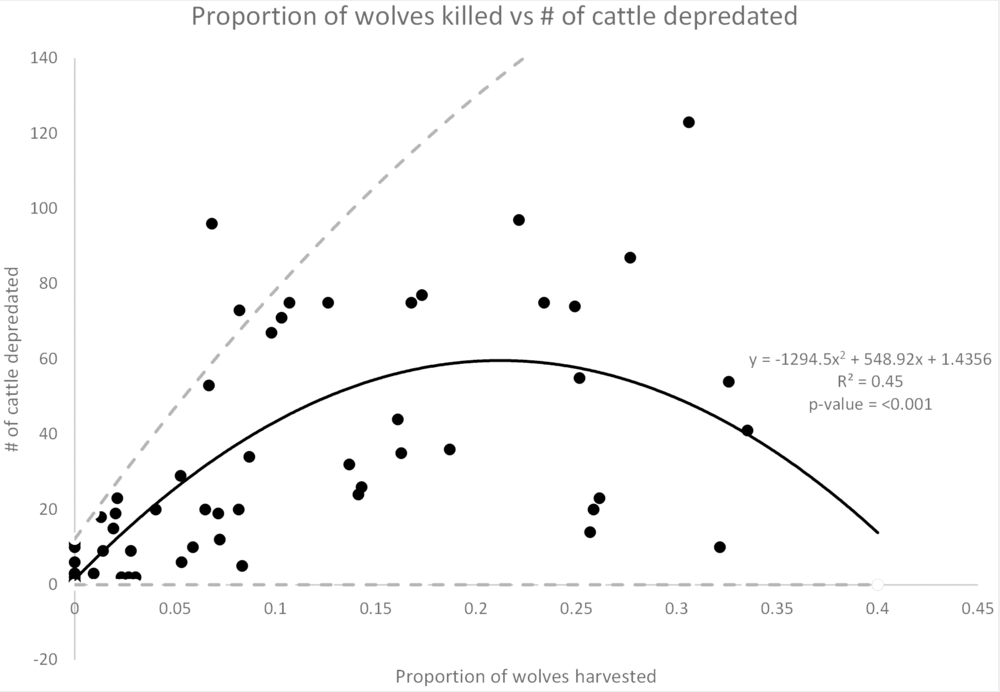

In an incredibly comprehensive and long term study, Wielgus et al. assessed the effects of a wolf cull on reducing livestock depredations in Idaho, Montana and Wyoming from 1987–2012 using a 25 year time series. The number of livestock depredated, livestock populations, wolf population estimates, number of breeding pairs, and wolves killed were calculated for the wolf-occupied area of each state for each year. Unsurprisingly, their results describe a positive association between the number of cattle in a given area, the number of cattle killed, and the number of breeding wolf pairs. In other words, as you increase the number of cows and wolves in a given area, instances of wolf-cow conflict will also rise. Incredibly, however, their data also shows a positive, not negative, association with the number of wolves culled the previous year – meaning culling wolves actually led to more livestock being killed by wolves the following year. “The odds of livestock depredations increased 4% for sheep and 5-6% for cattle with increased wolf control” (graphed in Figure 1.). Wielgus et al., hypothesized that livestock depredation increased when wolves were killed because the cull disrupted pack structures, which in turn, lead to a compensatory increase in breeding pairs, more pups, and more hunting (Figure 2.). This trend was consistent until 25% of the breeding wolf pairs had been culled, after which point livestock predations began to decline from its elevated state (graphed in Figure 3.). As the paper stresses, however, “mortality rates exceeding 25% are unsustainable over the long term.” As you can see in Figure 3., to get to the livestock mortality rate that you started with before the wolf cull elevated depredation levels, you would need to kill over 40% of the breeding wolf pairs. Ultimately, Wielgus et al. concluded that their results do not support the ‘remedial control’ hypothesis of predator mortality which predicts a drop in livestock following increased lethal control. “However,” they write, “lethal control of wolves appears to be related to increased depredation in a larger area the following year.”

Figure 1: Wolves killed versus cattle depredated: The number of wolves culled the previous year plotted against the number of cattle killed by wolves the following year. The black line indicates that as more wolves were killed through control methods, the remaining wolves killed an increased number of cattle. The dashed lines show the upper and lower limits of the 95% confidence interval for the best fit line.

Figure 2: Number of breeding wolf pairs versus cattle depredated: The number of breeding wolf pairs present in a region the previous year plotted against the number of cattle killed by wolves the following year. The black line indicates that as the number of breeding wolf pairs increases, so to does the number of cattle they kill. The dashed lines show the upper and lower limits of the 95% confidence interval for the best fit line.

Figure 3: The proportions of wolves killed versus cattle depredated: The proportion of wolves killed the previous year versus the number of cattle killed by wolves the following year. The black line indicates a 2-way negative interaction. Cattle depredation increased with increasing mortality up until roughly 25% of the wolf population was culled, then the number of cattle killed began to decline.

Echoing their conclusion from a different research angle, Brainerd et al. analyzed pooled data from 148 territorial breeding wolves and found increased movement and dispersal of wolves when the pack’s breeding (alpha) pair was removed. In other words, when you kill the alpha wolf pair who keep the rest of the pack in line, remaining wolves are statistically likely to breed more and spread into new territories. This disruption to the ecosystem is likely to trigger other changes and lead to issues to neighbouring environments.

Similarly, Treves et al. found that the removal of carnivores generally only achieves a temporary reduction in livestock depredation before other predators move in to fill their space and eat their prey. Harper et al. also found that killing a large number of wolves in Minnesota did not reduce the following year’s livestock depredation levels. They did notice, however, that a mere increase in human activity decreased the amount of hunting wolves did in the area.

Caribou Health

Credit: Mark Gocke, Wyoming Game and Fish

Unfortunately, there is yet another layer of concern to add to this complex analysis; caribou health. The University of Alberta’s Center for Conservation Biology began studying this issue after the government of Alberta announced plans to cull up to 80% of wolves in the oil sands in the hopes that it would slow the rate of caribou decline. They conducted dietary analyses had found that 60% of the caribou winter diet consisted of lichen. “This food source is particularly vital to pregnant caribou as it is high in glucose, which is the primary food source to the fetus,” they wrote. If female caribou do not have adequate access to lichen, they explained, it compromises their pregnancies and lowers birth rates.

“They [the government of Alberta] argue that climate change and habitat disturbance are causing deer, the preferred prey of wolves, to move north into the oil sands. Wolves are said to increase in response, increasing the risk of predation on caribou. Our work suggests that there may be better options.”

The conservation biologists suggested that reducing human and industrial activities in lichen rich feeding grounds may be a more effective mitigation strategy than killing wolves.

“Moreover,” they continued, “owing to the preference of wolves for deer, removing wolves from the population to protect caribou could actually place the ecosystem at markedly greater risk by accelerating the expansion of deer into this ecosystem.”

The Columbia Mountains Institute of Applied Ecology has picked up on this theme too. “Caribou decline may be related to too much energy spent on just trying to stay alive,” explained national park warden John Flaa. “Over the past summer, the three caribou mortalities I investigated had no body fat, which is bound to have an effect on calf production. Census results here show that the proportion of calves in the herd are below replacement level.”

Accessing an adequate food supply has been an ongoing issue for elk too, especially across the border in Wyoming. Their Game and Fish Wildlife Division, however, has managed to greatly inflate herd size over the last few decades by feeding them hay every winter. Not surprisingly, issues of disease began to increase as more elk congregated at feeding grounds. As Creech et al. explained; “High seroprevalance for Brucella abortus among elk on Wyoming feedgrounds suggests that supplemental feeding may influence parasite transmission and disease dynamics by altering the rate at which elk contact infectious materials in their environment.” Thankfully, they have also since shown that spreading out feeding areas reduces cross contamination infection rates by 70%.

This is not an ideal solution, of course, but it has been quite successful in many respects. Elk populations in Wyoming are now strong enough to support hunting, an activity that more than covers the cost of the feeding program. “Elk hunters spent $49.9 million in 2012… The program cost $558 per animal and generated $1,856 in ‘economic return’ per [elk].”

Conclusion

As Dr. Adam Ford wrote in his summary paper Science, Uncertainty, and Ethics in the Alberta Wolf Cull; “It is past time that we adopt a more creative view of how we can coexist with caribou and wolves in an industrialized landscape.” After reviewing the literature available on this and related issues I agree. While this is an undeniably complex situation with a lot at stake, I think we should be doing more to learn from innovative wildlife managers around the world.

We could try creating a geo-fence between wolves and threatened caribou like conservation officers do with their problem elephants in Kenya. Or get ‘caribou shepherds’ to track GPS collared herds, intervening when they are at risk of predation; much like the ‘marmot shepherds’ who saved endangered (admittedly easier to track) colonies on Vancouver Island. We could explore the feasibility of capturing, sterilizing, and re-releasing the alpha breeding pair in a pack of wolves; thereby reducing the growth of a wolf population while keeping the governing pack structure in place. Given the above concerns about food availability for caribou, as well as the effective use of feed lots elsewhere, I think we should also consider supplementing the diets of the South Selkirk and Peace region herds with a stable supply of lichen over the winter. It would be a relatively cost effective, simple, and could potentially be game-changing for our struggling caribou.

Some of these solutions may sound crazy, but when you consider we are currently spending millions of dollars to indiscriminately shoot wolves from helicopters, I would argue they potentially offer for more cheaper and less-crazy alternatives.

Acknowlegements

We are sincerely grateful to the many scientists who made time to talk to us about their work.